"OH MY GOD, IT'S MY BEEPER--THAT MEANS THEY FOUND A MATCH!" Jackie Warren Demijohn of Farwell, Michigan, yelled into the receiver at her boss on the other end. "I'll call you back; I've got to call Miami right away."

In a matter of minutes, Demijohn was on the phone with the Diabetes Research Institute (DRI) at the University of Miami. It would be another four hours before they would know for sure if the islet and bone marrow cells were a perfect match, but it was time for Demijohn to put in motion her well-rehearsed plan: Michigan to Miami as quickly as possible.

A Type 1 diabetic since the age of three, Demijohn had read about the work being done at the DRI with islets, the cells in the pancreas that produce insulin. Insulin is a hormone essential for life that enables the body to convert the foods we eat into energy. Because of a dysfunction in their immune systems, people with Type 1 diabetes, like Demijohn, have destroyed their own islet cells and can no longer make insulin. Without it, sugar can't enter the cells and a diabetic literally starves to death. Blood sugar levels fluctuate dangerously, unpredictably, and in time, cause permanent damage throughout the body.

To stay alive, Demijohn and millions like her have to check their sugar levels many times a day to determine how much hormone they need, and then inject themselves with the proper dosage of insulin. Even then, they cannot control the crippling complications that diabetes inevitably brings: loss of vision, kidney failure, nerve damage, and premature death. For the 16 million Americans who live with this disease, the DRI represents their best hope for conquering the seventh leading cause of death in this country.

![]() ive minutes

before boarding, Demijohn called the DRI one last time to see

if she should cancel her flight. "Get on the plane, Jackie,"

the nurse said. "Hurry, it's a match!"

ive minutes

before boarding, Demijohn called the DRI one last time to see

if she should cancel her flight. "Get on the plane, Jackie,"

the nurse said. "Hurry, it's a match!"

Two days later, Demijohn became the first person in the country to receive islets and bone marrow cells from the same donor, without also having to receive another transplanted organ. As one of a very select group of participants in a long awaited clinical trial, Demijohn will be taken off all anti-rejection drugs at year's end to see if her body has accepted the transplanted islet cells and if they will continue to produce insulin.

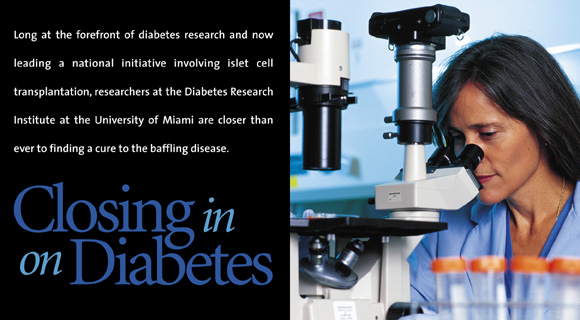

With an emphasis on translational research, the scientific team at the DRI has been at the forefront of the race to cure diabetes.

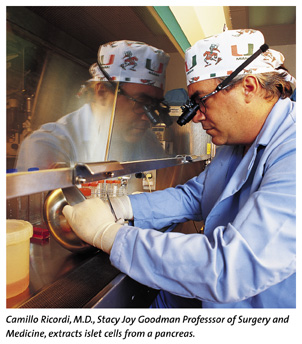

"Every experiment that is pursued here is done with the patient application in mind," explains Camillo Ricordi, M.D., Stacy Joy Goodman Professor of Surgery and Medicine, and scientific director of the DRI. "If you're a mouse and have diabetes, you're lucky. There are hundreds of ways to cure your disease. But how do you translate a mouse-proven idea into therapeutic strategies for people?

"There are children being diagnosed with diabetes every day, and they and countless others are counting on us to find a cure for their disease," he continues. "That is what the DRI is all about, linking laboratories to life."

![]()

The approach sounds simple enough, but for many other centers,

it requires a retooling of the way research has been done. Now

each scientist must pursue answers to questions while keeping

an eye on the prize: How can my research be translated to help

people who suffer from the disease? Instead of testing all possibilities

at the mouse level, for example, the translational approach would

require that a scientist take one promising finding and work

to quickly move it up the evolutionary ladder to larger animal

models that more closely mimic how the disease works in people.

"Fast-tracking science is now a buzzword at many centers, but the DRI has been doing it for years," says Luca Inverardi, M.D., research associate professor of medicine and head of basic research at the DRI. "Everyone, including our postdoctoral fellows, conducts investigations believing that as little time as possible should be spent between the study of the molecule and the cure of the disease. This has speeded up our productivity."

The results have paid off for the DRI with a long list of scientific accomplishments (see sidebar). More and more potentially curative findings are making their way down the pipeline for testing at the pre-clinical stage, and they are arriving faster then ever before.

"Promising findings made in basic science labs need to be tested in models that have more complicated immune systems because these systems are much more relevant to patients with diabetes," says Norma Kenyon, Ph.D., associate professor of medicine and director of pre-clinical research at the DRI. Under Dr. Kenyon, the DRI team was able to use a new type of immune intervention to prevent transplant rejection in monkeys with diabetes. The result was the first successful islet cell transplant that produced long-term (over a year) insulin independence in this very relevant model.

But it seems that as scientists move further along in the translational process and come closer to applying a new therapy to patients, the more possibilities there are to contend with. "Think of all the possible combinations of highways, interstate, and off-the-map roads that you could take to cross the United States from coast to coast," Dr. Kenyon explains. "That is the number of pathways we have to deal with in human immunology. We now have a much better map than we had five years ago."

![]() ot only

do academic researchers recognize the unique opportunity that

the DRI represents to speed progress in diabetes research, but

industry does as well. In increasing numbers, biomedical companies

are teaming up with the DRI to test innovative technology. Calling

on the DRI's proven ability in translational research, firms

have tested everything from now-familiar medications for erectile

dysfunction to implantable insulin delivery capsules that are

still in development and as yet commercially unavailable.

ot only

do academic researchers recognize the unique opportunity that

the DRI represents to speed progress in diabetes research, but

industry does as well. In increasing numbers, biomedical companies

are teaming up with the DRI to test innovative technology. Calling

on the DRI's proven ability in translational research, firms

have tested everything from now-familiar medications for erectile

dysfunction to implantable insulin delivery capsules that are

still in development and as yet commercially unavailable.

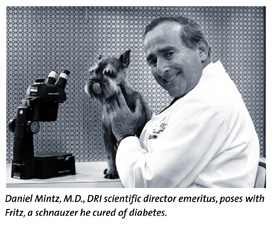

The DRI's state-of-the-art laboratories, combined with its open-door attitude toward investigators, has been key to the DRI's transformation. What began in the 1970s as a discrete, visionary University program under the auspices of Daniel Mintz, M.D., the DRI's scientific director emeritus, is now a turnkey research operation involved in the most sophisticated translational projects in diabetes.

Today, the DRI's position at the vanguard of cure-related diabetes research in the United States was confirmed in a recent decision by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The DRI is the only academic center selected to partner with the NIH and the U.S. Navy for a new national initiative to cure diabetes through islet cell transplantation.

According to David Harlan, M.D., the director of the Navy/NIH Transplantation and Autoimmunity branch that will oversee the partnership, the choice was clear. "I was fortunate to meet Drs. Ricordi and Kenyon at an immu-nology conference several years ago," he recalls. "That relationship has evolved into a formal partnership between our two institutions and even given rise to a new branch at the NIH. This partnership will allow us to determine if the new techniques that work in very complex pre-clinical models will work in people. In planning this next phase, the clinical studies, there was no question that we needed the renowned experts in islet cell isolation on our team."

The promise that these NIH/DRI studies represent has generated great interest in the scientific community and hope among diabetic patients and their families. In addition, many islet cell transplantation programs have sprung up at other medical centers across the country as a result of a renewed interest in the field. The DRI is serving as mentor to many new transplantation teams as they acquire experience in islet cell isolation and transplantation.

For Demijohn, these advances have enabled her to see herself as a different person, even though the clinical trial is far from over. "I never used to think of retirement, for example, because I never believed I would live long enough. The future used to be next week or next month, and nothing beyond that."

Today, Demijohn says she's never been better. "Now I have energy, I'm not depressed, my blood sugars are more stable each day, and I have a life and a future. I can't thank the DRI enough for giving me back my life."

Milestones in Diabetes Research

![]() he DRI

has achieved many scientific accomplishments since 1975, among

them:

he DRI

has achieved many scientific accomplishments since 1975, among

them:

1976 Islet cells successfully transplanted into rats with diabetes, producing a cure for the disease in small animals.

1978 Using a new home blood glucose monitoring system, DRI researchers develop a successful treatment regimen for pregnant women with diabetes.

1984 The DRI team conducts the first successful transplant of islets into dogs with spontaneous diabetes.

1985 An islet cell transplant

is performed in a patient requiring immunosuppression for a transplanted

kidney and results in a 75 percent reduction of the patient's

insulin requirement for almost one year.

1985 An islet cell transplant

is performed in a patient requiring immunosuppression for a transplanted

kidney and results in a 75 percent reduction of the patient's

insulin requirement for almost one year.

1988 Camillo Ricordi, M.D., develops the automated method, currently used around the world, for isolating large numbers of islets. This technology makes it possible to consider a wider application of islet cell transplantation as a potential cure for diabetes.

1990 Nine patients receive islet cells with their multi-organ transplants. This study demonstrated that islets were capable of producing insulin independence in patients who had their pancreas removed because of cancer.

1992 Experiments with islet cell transplants prove that it is possible to reverse diabetes, achieving complete insulin independence in pre-clinical models, without the use of continuous immune system suppression.

1997 DRI researchers, in collaboration with the University's Division of Transplantation, demonstrate that multiple infusions of bone marrow cells can improve the survival of transplanted organs.

1998 The first clinical trial begins in which patients can receive islet cells without requiring a simultaneous transplant of another organ.

1999 The NIH selects the DRI as a partner, together with the Naval Medical Research Center and the Walter Reed Army Medical Center, for its federal transplant initiative to cure Type 1 diabetes. Clinical trial recruitment begins.