ear

a path of vibrant hibiscus and a rainbow garden of impatiens

in Miami stands a monument that celebrates the perpetual act

of giving life. Its simplicity expresses gratitude to the millions

of organ and tissue donors who "in their last hour gave

a lifetime."

ear

a path of vibrant hibiscus and a rainbow garden of impatiens

in Miami stands a monument that celebrates the perpetual act

of giving life. Its simplicity expresses gratitude to the millions

of organ and tissue donors who "in their last hour gave

a lifetime."

Through publicity efforts over the years, the links between organ and tissue procurement, donation, and life-saving have become clear. But one aspect of this combination has received little attention: securing donations can serve dual purposes. Organ and tissue donations benefit the patients who receive transplants. At times, the donations also can be used for research that can lead to the discovery of treatments and cures for disease.

Perhaps, it is no accident that the organ and tissue donation monument stands in the heart of the University of Miami School of Medicine, which houses four reservoirs of organs, bone tissues, corneas, and even living cells that are used daily to improve people's quality of life and advance scientific research.

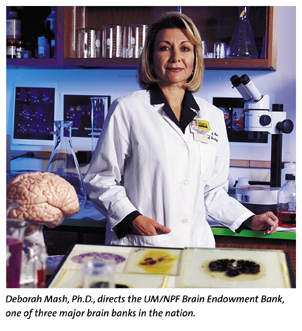

One of these repositories is the University of Miami/National Parkinson's Foundation (UM/NPF) Brain Endowment Bank, where mysteries of brain function and default are waiting to be discovered in samples locked away in two stainless steel freezers. The UM/NPF Brain Endowment Bank, established in 1986, is one of three major brain banks in the nation, providing free distribution of tissue samples to hundreds of researchers studying brain-based illnesses.

Behind the collection and disbursing of the tissues is Deborah Mash, Ph.D., director of the program and Jeanne C. Levey Professor of Neurology and Molecular and Cellular Pharmacology. With an intense passion and conviction for her work, Dr. Mash poses the morbid question about brain donation during her educational presentations around the country. But her requests are always followed with a handful of reasons why brain donation is the key to understanding the mind's intricacies.

So far, her efforts have produced 800-plus commitments from

healthy people who will donate their brains to science after

death. This count does not include the hundreds of samples already

in stock ready for study. The brain tissues are provided, along

with the donor's medical history and information about their

lifestyle, to help researchers make links between life events

and brain activity.

![]()

"You can't study a disease of the brain without having a

healthy brain for comparison, and I think one of the most significant

movements to develop brain banks around the nation has been associated

with Alzheimer's disease," says Dr. Mash, who hopes to reach

1,000 donations by 2001. "Many times we don't have even

simple models that can be worked on in the laboratory and that

can be accurate representations of what goes on in the human

brain. Let's face it, there is no comparison to having the actual

human brain for study."

Presently, an Alzheimer's diagnosis can only be confirmed through a brain autopsy. Dr. Mash hopes that brain donations from a diverse group of donors, including African-American and Hispanic populations, can help make sense of the genesis and progression of many neurodegenerative diseases.

"It is estimated that one in five elderly across the nation will be afflicted with some type of dementia by the turn of the century," she says. "That's a heavy price tag. So, the race is on in trying to understand why some people remain so sharp into their eighth, ninth, and tenth decades, and others fall victim to the debilitating illnesses of Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases."

Also on the brink of new discoveries and treatments yielded through organ donation is the Diabetes Research Institute (DRI). The DRI stores and distributes worldwide two types of cells: pancreatic islet cells and bone marrow stem cells. These cells are used both for research applications and in clinical trials. Camillo Ricordi, M.D., Stacy Joy Goodman Professor of Surgery and Medicine and the scientific director of the DRI, has established an islet cell repository for the purpose of testing experimental treatments for diabetes, such as islet cell transplantation. Islets are clusters of cells in the pancreas that produce insulin, an essential hormone that enables the body to break down sugar and turn food into energy. Patients with Type 1 diabetes lack islet cells, clusters of which are about half a millimeter in diameter, and their bodies can no longer produce insulin.

In the late-1980s, Dr. Ricordi developed a technology, or automated method, to extract clusters of cells (for example, islet cells) from organs. Basically, the procedure allows organs to be "disassembled," in order to obtain clusters of cells, such as islet cells from the pancreas or hepatic cells from the liver. Referred to as the Ricordi Method, it can produce several hundred thousand insulin-producing islet cell clusters from a human pancreas in four to six hours.

In experimental clinical procedures, doctors have been successfully injecting purified islet cells into the portal vein that drains directly into the liver, which is the natural first target of pancreatic endocrine secretions in the body. The liver traps and nourishes the islet cells, which soon become part of the liver's chemistry, turning the liver into a "double organ" that performs the function of both liver and the endocrine pancreas.

In 1996, Dr. Ricordi's team of scientists took islet transplantation to another level and launched a pilot study to test if bone marrow infusions, given at the same time as islet cells from the same donor, can decrease or eliminate the need for drugs that suppress the immune system to prevent rejection of the transplanted islets. If successful, this trial will usher in a promising, new era of diabetes research that will focus on the curative potential of islet cell transplantation.

![]() et another

reservoir that provides hope to thousands of people who lose

their sight or eyes to injury or disease is the Florida Lions

Eye Bank, located on the third floor of the University of Miami

Bascom Palmer Eye Institute. This nonprofit charitable organization,

founded in 1962, has provided more than 35,000 free corneas to

patients in need of transplant surgeries throughout Florida.

Annually, more than 500 sclera tissues (comprising the white

area of the eye) are used for reconstructive surgical procedures

and glaucoma surgery. From one pair of eyes, two patients can

regain vision through corneal transplantation and approximately

16 others can receive pieces of donor sclera for glaucoma surgery.

The sclera is employed as a padding to support a microscopic

tube that helps release pressure caused by glaucoma.

et another

reservoir that provides hope to thousands of people who lose

their sight or eyes to injury or disease is the Florida Lions

Eye Bank, located on the third floor of the University of Miami

Bascom Palmer Eye Institute. This nonprofit charitable organization,

founded in 1962, has provided more than 35,000 free corneas to

patients in need of transplant surgeries throughout Florida.

Annually, more than 500 sclera tissues (comprising the white

area of the eye) are used for reconstructive surgical procedures

and glaucoma surgery. From one pair of eyes, two patients can

regain vision through corneal transplantation and approximately

16 others can receive pieces of donor sclera for glaucoma surgery.

The sclera is employed as a padding to support a microscopic

tube that helps release pressure caused by glaucoma.

From a research perspective, nothing is wasted. In a massive refrigerator kept at 39 degrees Fahrenheit, additional donor eyes are stored. These eyes-unsuited for transplantation-are used by researchers in the Ophthalmic Biophysics Lab at the McKnight Vision Research Center to design new equipment and techniques. Ophthalmologists also use them to practice new surgical procedures.

"It's amazing that techniques used in laser surgery were all developed through the use of human donor eyes," says Mary Anne Taylor, executive director of the Florida Lions Eye Bank.

In many cases, advances in eye care don't necessarily come from donors, but from patients who have lost their eyes to disease or tumors. Every week, hundreds of eye specimens are received at the ocular pathology lab in the Florida Lions Eye Bank. Medical director Robert H. Rosa, Jr., M.D., evaluates the specimens for diagnoses and treatment. Microscopic slides of the diseased eyes are prepared and stained for study.

"The microscopic slides help determine what the disease process is. A report is generated and returned to the ophthalmologist who performed the surgery," Taylor says. "The report helps the ophthalmologist determine how best to treat the patient, whether the patient needs additional therapy, or whether the doctors need to keep a close watch on the other eye."

The value of this service comes full circle when ophthalmology residents use the slides to perfect their diagnoses and gain knowledge of how to treat a full range of eye diseases.

Sometimes, it is not an eye or an infusion of islet cells that a patient needs. "The most frequent transplantation, aside from blood, is bone and skeletal tissues," says Theodore I. Malinin, M.D., a prominent researcher in the science of preservation and application of donated bone, skin, and other tissues.

"Some of these transplants are tissues taken from patients themselves and put in different locations in the same patient," he explains. "A large number of them are taken from deceased individuals. For that reason we have a tissue bank. We furnish transplants for about 10,000 patients a year." Dr. Malinin runs the University of Miami Tissue Bank, which he established in 1970.

![]() he UM Tissue

Bank maintains a repository of cartilage, tendons, ligaments,

and dura mater, the membrane that covers the brain. Some of the

tissues are kept in giant steel cylinders at temperatures of

minus 150 degrees Celsius. One set of cylinders contains quarantined

tissues that are being tested for disease or microbes. Other

cylinders are located in the distribution room, holding tissues

ready for transplantation. Surgeons request these donations to

replace diseased tissue or tissue damaged by trauma. To realize

the importance of having a tissue bank, one only needs to know

about the patients who take advantage of these donations.

he UM Tissue

Bank maintains a repository of cartilage, tendons, ligaments,

and dura mater, the membrane that covers the brain. Some of the

tissues are kept in giant steel cylinders at temperatures of

minus 150 degrees Celsius. One set of cylinders contains quarantined

tissues that are being tested for disease or microbes. Other

cylinders are located in the distribution room, holding tissues

ready for transplantation. Surgeons request these donations to

replace diseased tissue or tissue damaged by trauma. To realize

the importance of having a tissue bank, one only needs to know

about the patients who take advantage of these donations.

"People who get bone tumors in their 20s and 30s need to have a large portion of the bone removed," Dr. Malinin explains. "If you can't restore the limb's function, you might have to amputate it. As a substitute for amputation, we have devised a limb-sparing surgery where we remove the bone with tumor, replace it with an allograft bone, and restore as much functionality of the limb as possible."

The second largest group of people who use the bank are the elderly. Although many hip replacement procedures are performed successfully, the metal implants sometimes wear out the bone and eventually create bone loss. Allografts, using actual human tissue, are transplanted to restore lost bone stock.

With so many patients reaping the benefits of this storage system of organs, bones, and tissues, a new era in medicine is emerging. With every brain donation, researchers get closer to unveiling the mysteries of the mind. With every pair of donated eyes, more people see the light of day. With every bone tissue used, a young person is spared losing a limb. And the possibility of diabetics becoming insulin-free already exists with islet cell transplantation. These wonders of science, and those awaiting discovery, will continue as long as there are donors who, in their last hour, give a lifetime.

How to Become a Donor

![]() hen deciding

to become an organ or tissue donor, share your decision with

your family so they are informed and can carry out your wishes.

The following is a list of procurement centers you can call to

ask questions, receive printed information, or sign up as an

organ-tissue or brain donor. You must sign up directly with the

Brain Bank to be considered a brain donor.

hen deciding

to become an organ or tissue donor, share your decision with

your family so they are informed and can carry out your wishes.

The following is a list of procurement centers you can call to

ask questions, receive printed information, or sign up as an

organ-tissue or brain donor. You must sign up directly with the

Brain Bank to be considered a brain donor.

University of Miami Organ Procurement Organization

1150 NW 14th St., Suite 202A

Miami, Florida 33136

800-232-2892

Florida Lions Eye Bank

P.O. Box 016880

Miami, Florida 33101-6880

305-324-4340

University of Miami Tissue Bank

P.O. Box 016960 (R-12)

Miami, Florida 33101

305-243-6465

The UM/NPF Brain Endowment Bank

1501 N.W. Ninth Ave., #4013

Miami, Florida 33136

305-243-6219 or

800-UM-BRAIN (862-7246)