What Drives Basic Research?

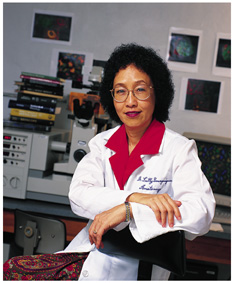

![]() y colleagues at the Diabetes Research Institute (DRI)

and the UM/Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center place a great

deal of importance on translational medicine and moving research

findings more quickly into the clinical setting. As a basic scientist,

I support their vision. I will even go so far as to state that

I would not apply for, or enter into projects that don't show

scientific advancement with clinical relevance.

y colleagues at the Diabetes Research Institute (DRI)

and the UM/Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center place a great

deal of importance on translational medicine and moving research

findings more quickly into the clinical setting. As a basic scientist,

I support their vision. I will even go so far as to state that

I would not apply for, or enter into projects that don't show

scientific advancement with clinical relevance.

There are misconceptions today that clinical collaboration

somehow means science is compromised. I beg to differ. Untargeted

research has always had a place in medical research. Without

it, smallpox, polio, and pneumonia still would be killers and

cripplers. But what moved Jonas Salk's polio vaccine out of the

lab and into application was his clinical collaboration, which

today remains one of the largest trials ever conducted. Many

of us recall the long lines of people receiving the vaccination

that led to polio's eradication. This is what biomedical research

is all about. The way I see it, if I'm a basic scientist at a

medical school, why not ask the clinical questions?

To attack diseases such as

cancer, heart disease, and diabetes, we need a broader base of

knowledge that provides much faster results in moving our findings

from labs to clinical trials. Collaboration between scientists

and clinicians can shorten the time to develop effective treatments

for the patient. The bottom line: More resources and support--whether

financial, human, or scientific-facilitate faster exchange and

progress.

To attack diseases such as

cancer, heart disease, and diabetes, we need a broader base of

knowledge that provides much faster results in moving our findings

from labs to clinical trials. Collaboration between scientists

and clinicians can shorten the time to develop effective treatments

for the patient. The bottom line: More resources and support--whether

financial, human, or scientific-facilitate faster exchange and

progress.

Speaking of the bottom line,

another reason collaboration has become so vital is that the

National Institutes of Health, the primary U.S. funding source

for basic science research, has begun requiring collaboration

in its proposals. Both government and private funding sources

favor projects for which clinical utility can be demonstrated;

NIH focuses more on proposals that include disease-relevance

information.

Speaking of the bottom line,

another reason collaboration has become so vital is that the

National Institutes of Health, the primary U.S. funding source

for basic science research, has begun requiring collaboration

in its proposals. Both government and private funding sources

favor projects for which clinical utility can be demonstrated;

NIH focuses more on proposals that include disease-relevance

information.

Public opinion has influenced the direction of clinically relevant

research during the last decade. Taxpayers who fund NIH research,

as well as public interest groups such as breast cancer survivor

organizations, are demanding greater accountability and faster

results.

I am often referred to as a cancer cell biologist; however, only

five or six years ago, my laboratory was still pursuing relatively

untargeted basic science research. In recent years, the NIH and

Army Breast Cancer Medical Research Program directive motivated

scientists and clinicians to collaborate. In fact, some of our

current work with clinical investigators at UM/Sylvester is a

result of these initiatives. My clinical colleagues knew that

as a cell biologist, I had an in-depth understanding of cellular

regulation. When certain cells behave inappropriately during

cancer progression, it is vital that we identify and characterize

the abnormal cellular segregation, movement, growth, and signaling

that "turns on" cancer cells, making them so deadly

and resistant to treatment.

And that was just the beginning. Now, I also collaborate with

colleagues at the DRI, Parkinson Foundation, and others on the

medical campus. Our combined creativity plays a major role in

establishing hypotheses for our projects.

It is important for basic scientists to forecast their involvement

in future clinical advances and requirements. We need to be innovative

and recognize that high-risk research projects yield high return.

We can no longer do the same old closed-door laboratory science

if we expect to contribute to the advancement of medical science.