|

|

|

Even though the medical center will be taking the lead, the scope of a terrorist attack would be so great that no one institution could handle it alone. “Although JMH has shouldered the burden of trauma care over the years, we view disaster readiness as a community affair,” explains Gold, who is also co-chair of the WMD advisory committee. “It’s imperative that our plan include peer hospitals countywide and take advantage of what they can contribute in terms of medical resources, right down to faith-based organizations that would help with the psychological footprint of a disaster at the neighborhood level.”

The advisory board prepared responses to four types of attack: conventional, chemical, biological, and radiological. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) dictates that medical facilities should be prepared to treat 500 patients per million in population, which means Miami-Dade’s hospitals should be geared to care for 1,150 patients based on a population of 2.3 million. JMH is prepared to take 300 of the most critically injured victims, with the other hospitals dividing the remaining 850 victims with less severe injuries, based on their capacity and medical staff expertise.

Conventional Attack

|

||

|

||

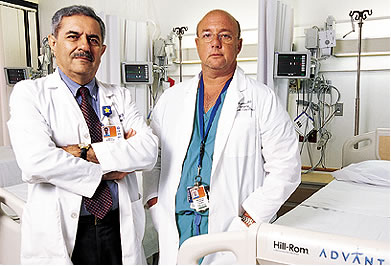

A conventional attack would most likely involve a bombing with a large number of casualties. The first priority: make room for the victims. “We would be turning single rooms into doubles with an extra stretcher or bed, using our inter-hospital mutual aid agreement to transfer patients to other hospitals and discharging as many as possible,” says Abdul Memon, M.D., chief of emergency services and co-chair of the WMD advisory committee.

“We had a real-life testing of the plan during the cruise ship boiler room explosion at the Port of Miami in May of last year,” remembers Memon. “In just 50 minutes, we freed up 26 beds.”

While attacks on American soil are a relatively new occurrence, Mauricio Lynn, M.D., medical director of trauma resuscitation and mass casualty intake management, has had extensive experience with terrorism. Before coming to UM in 2000, he served nearly 20 years in the Israeli Defense Forces, mostly as a medical surgeon and most recently as the lieutenant colonel in charge of trauma. He brings a unique perspective to the process.

“Israel has had a lot of practice in dealing with mass casualty incidents. And over the years they’ve adopted standard protocols that are used for every hospital in the country and are overseen by a national office of emergency management,” says Lynn. “We’ve taken the guidelines used in Israel and adapted the basic concept.”

Lynn has developed a system for rounding up staff, designated meeting points, and devised red, yellow, and green categories for patients based on severe, moderate, and mild triage situations. The floors in the trauma/emergency area are marked with the colors so staff will know where to take patients; they will have a corresponding colored chart, with a specific number of physicians and nurses assigned to each category.

Chemical Agents

|

The hospital’s decontamination team might find itself battling blister agents such as mustard gas, nerve agents such as sarin, or biotoxins such as ricin. “The chemical agents are horribly toxic, and it would be up to the decontamination team to save as many patients as possible, while not putting themselves or others nearby at risk,” says Richard Weisman, Pharm.D. As director of the Florida Poison Information Center at UM/Jackson, he’s in charge of planning for just such an attack.

The decon team includes 180 people, from physicians to members of the housekeeping staff. Trained by Weisman and Jeffrey Bernstein, M.D., they are on call 24 hours a day. In the event of an attack, they will suit up, take the victims to the decontamination center, and bring them into the hospital for treatment.

An elaborate collection of equipment has been assembled to outfit the decon team. Depending on the chemical involved, the members will choose from five different protective suits, several types of boots and gloves, gas masks with four or five different filters, and air-pressure respirators. The decon center has showers to wash down victims, along with an airway stabilization area equipped with portable intubation kits. During the entire emergency, the Poison Control Center would be hooked up via satellite with the CDC so they could jointly determine the chemical agent and the course of treatment.

Biological Terrorism

Unlike other types of attacks, biological terrorism would sneak up on health care workers, making education essential, according to Alan Hartstein, M.D., hospital epidemiologist. For instance, if terrorists were using tularemia or plague, the first sign might be an increase in deaths of dogs and cats. A well-trained health care worker might be the first to notice a suspicious rash that could be smallpox. “Everyone is trained in how to recognize the symptoms of a category A agent of bioterrorism,” says Hartstein. “For instance, if someone did suspect and then diagnose smallpox, that’s considered a public health and medical emergency, since there has been no naturally occurring case of smallpox anywhere in the world since 1977.”

The CDC’s category A list of bioterriorism agents includes those that can be disseminated in the air and have a high mortality rate. In addition to tularemia, smallpox, and plague, anthrax and viral hemorrhagic fevers are on the A list. Also, smallpox and the viral hemorrhagic fevers may be transmitted from person to person via small respirable particles. “These two airborne infectious diseases are the most difficult because you need a special type of room with negative air flow, and staff needs special breathing devices,” Hartstein says.

Seventeen rooms in the emergency and urgent care centers already have been converted to negative air flow with special filtration capability.

Radioactive Threats

|

||

The most likely radiation attack would be something like a “dirty bomb,” which is a conventional explosive that disperses a radioactive material. “This type of attack would most likely cause damage and injury in a limited area, but the psychological damage could be severe,” says Edward Pombier, director of the Radiation Control Center at the School of Medicine.

For those exposed to the radiation and not actually injured by the explosion, decontamination is the first priority. Clothes should be removed and bagged and victims should shower.

The medical center also is equipped with different radiation detection devices. A portal monitor can detect radioactive material on a victim, a digital dosimeter can monitor caregivers, and a hand and foot monitor can help limit the spread of contamination. A radiation spectrometer can identify the specific isotope involved in the incident.

Mental health needs also will be paramount in any attack. The DEEP (Disaster Epidemiology and Emergency Preparedness) Center at the School of Medicine is involved in behavioral health training across the state. “Individuals respond in a variety of ways to disaster stress, and it’s imperative that our behavioral health experts be ready from the hospital level down to the community level,” says Jim Shultz, Ph.D., director of the DEEP Center. The Center for Research in Medical Education continues to lead the statewide initiative to train first responders. Emergency medical response teams will be first on the scene in any type of terrorist attack, and their work in the field paves the way for what happens at the hospital.

As Weisman puts it, “Right

now I would say we are one of the best prepared U.S. medical centers,

but the team is not finished

yet. We must

continue to plan for the unthinkable and hope it never happens”.

Jeanne Antol Krull is director of media relations in the Office of Communications at the School of Medicine. Photography by John Zillioux.