|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

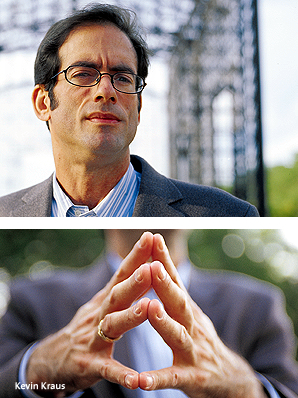

And even though Hilton knew people who were infected with the virus, she, like Kevin Kraus, was terrified. She kept picturing the emaciated, lesion-riddled AIDS patients of the disease’s early days and thought, ”Oh, I’m going to look like a monster. I saw those people and I thought I would look that way.”

Hilton, the mother of four, takes her medications religiously, takes care of herself, and now helps educate others about the risks and myths of HIV. She is “undetectable”—meaning the levels of HIV-1 RNA measured in her blood show a low level of virus activity. But though more and more HIV-positive patients are comparable to Hilton, they don’t necessarily react to the disease like she has.

For the past five years, the media have increasingly

focused on the alarming—and

rising—rates of Haitians, African-Americans, and Hispanics infected

with HIV/AIDS. Physicians and scientists at the University of Miami are

not surprised. Margaret Fischl, M.D., professor and director of the Section

of Special Immunology, and Gordon Dickinson, M.D., professor of medicine

and chief of the Division of Infectious Disease, first noted the increasing

rate of infection in the Haitian community—in 1983. “Miami

has always been a pace ahead of the epidemic nationally,” says Fischl.

For the past five years, the media have increasingly

focused on the alarming—and

rising—rates of Haitians, African-Americans, and Hispanics infected

with HIV/AIDS. Physicians and scientists at the University of Miami are

not surprised. Margaret Fischl, M.D., professor and director of the Section

of Special Immunology, and Gordon Dickinson, M.D., professor of medicine

and chief of the Division of Infectious Disease, first noted the increasing

rate of infection in the Haitian community—in 1983. “Miami

has always been a pace ahead of the epidemic nationally,” says Fischl.

Despite two decades of research, education, and efforts by health care workers to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS, 2003 was still the most destructive year on record for the disease. Last year more than five million people were infected and three million died worldwide. In the United States alone, new cases of HIV increased by 5.1 percent between 1999 and 2002. The state of Florida is third in the nation in the total number of AIDS cases, second in the number of pediatric cases. Miami-Dade County ranks first in the state in the number of HIV/AIDS patients.

From the earliest and darkest days of HIV/AIDS,

UM’s medical community

has been a leader in the research and treatment of the disease. Many of

the world’s foremost experts in the field are at the School of Medicine,

including Fischl and Dickinson; Gwendolyn Scott, M.D., director of the

Division of Pediatric Infectious Disease and Immunology; Clyde McCoy, Ph.D.,

professor and chair of the Department of Epidemiology and Public Health

and director of the Comprehensive Drug Research/Health Services Research

Center; and Mary Jo O’Sullivan, M.D., vice chair and medical director

of research in obstetrics and gynecology. A multidisciplinary approach,

combined with the trendsetting tendency of Miami’s HIV/AIDS epidemic,

has enabled the team to project the future of the disease and guide research

and treatment accordingly.

From the earliest and darkest days of HIV/AIDS,

UM’s medical community

has been a leader in the research and treatment of the disease. Many of

the world’s foremost experts in the field are at the School of Medicine,

including Fischl and Dickinson; Gwendolyn Scott, M.D., director of the

Division of Pediatric Infectious Disease and Immunology; Clyde McCoy, Ph.D.,

professor and chair of the Department of Epidemiology and Public Health

and director of the Comprehensive Drug Research/Health Services Research

Center; and Mary Jo O’Sullivan, M.D., vice chair and medical director

of research in obstetrics and gynecology. A multidisciplinary approach,

combined with the trendsetting tendency of Miami’s HIV/AIDS epidemic,

has enabled the team to project the future of the disease and guide research

and treatment accordingly.

PROMISES AND HARSH REALITIES

After their success in finding treatments for the disease, the school’s doctors and scientists are now pinpointing their next moves, such as shifting from preventing primary infection to a new focus on secondary prevention, which targets those already infected and moves them into treatment and counseling to prevent additional infections. Fischl notes there are many new drugs out there and more in the pipeline; future research will try to determine the best outcome and fewest side effects through different strategies and combinations. Other School of Medicine initiatives include developing a vaccine and partnering with international health care workers. It’s become another race against time, because experts agree that the epidemic is starting on another upward swing—and the prognosis for the immediate future is not good.

![]() Here’s the recipe for disaster: Start with large quantities of infected

youth with a life-threatening disease but no fear of death. Toss in rebellion,

adolescent hormones, and rage against a disease that many of them inherited

at birth. Add peer pressure and complacency. Top it off with a lot of “baggage”—as

Ann Carter, chief operating officer of UM’s Comprehensive AIDS Program,

puts it—poverty, barriers to access, and lack of education. You now

have all of the ingredients for the next wave of the epidemic. And here’s

what it looks like:

Here’s the recipe for disaster: Start with large quantities of infected

youth with a life-threatening disease but no fear of death. Toss in rebellion,

adolescent hormones, and rage against a disease that many of them inherited

at birth. Add peer pressure and complacency. Top it off with a lot of “baggage”—as

Ann Carter, chief operating officer of UM’s Comprehensive AIDS Program,

puts it—poverty, barriers to access, and lack of education. You now

have all of the ingredients for the next wave of the epidemic. And here’s

what it looks like:

Rhonda, 18, takes five pills every day. She gets her blood drawn every three months. Born with the virus, she has always done this. When she was younger, Rhonda “kind of thought maybe every child went through this.” But a few years ago, the longtime patient of Scott decided she didn’t want to take her medications anymore. Rhonda was resentful that her younger brother is not infected. She was shuffled from place to place as relatives died and homes became unstable. She did not like taking her pills and became, as she describes it, “a little wild.” Now Rhonda credits Scott and her case workers with keeping her in line and on her medications. Still, she notes that a close friend of hers always followed through with his treatment—and recently passed away. In a voice barely above a whisper, Rhonda says it showed her “that somebody can do the right thing and bad things still happen.”

Ana Garcia, a licensed clinical social worker and adjunct assistant professor who works with Scott and Rhonda, is dismayed to hear that. Garcia knew Rhonda’s friend very well; he was part of the Cool Kids group that meets every Friday in the School of Medicine’s Batchelor Children’s Institute. And Garcia also knows that this young man most likely did not take his medications—at least not consistently.

Now that there is effective treatment for HIV/AIDS, adherence and resistance to treatment have moved up the list as the top concerns of the epidemic in 2004. “Taking your pills most of the time is the worst thing you can do. Humans being humans, that’s often where we find ourselves,” Dickinson says. Starting and stopping treatment gives the virus time to figure out how to fight a drug; what doesn’t kill the virus makes it come back stronger.

Garcia looks at the children she encounters every day and sees “ticking time bombs.”

Carter agrees: “I’m afraid of what will happen in the next couple of years.”

TRENDSETTING MIAMI

More than 20 years after HIV/AIDS was identified, it’s hard to remember how little was known—and how much was feared. “This was a disease where every single person—despite the best efforts of their caregiver—died,” says Richard Iacino, then the administrative coordinator of the group of medical specialists who banded together to search for care and treatment methods. Caregivers were particularly courageous because no one knew anything about the disease’s transmittal. They had no idea if just being exposed to a patient put them at risk, or “if they wiped away the tears of a toddler they would get sick,” says Iacino, now assistant vice president for health program development and the dean’s chief of staff. Some health care workers would cover themselves from head to toe before seeing patients. Some wouldn’t see those patients at all.

|

||

|

||

In 1987 Fischl, chosen by the National Institutes of Health to participate in its AIDS Clinical Trials Group, began a series of studies using a new drug called zidovidine (AZT) as a treatment for AIDS. Kraus was one of her first patients.

The fact that he is still alive today is testament to those groundbreaking studies and to the tenacity of Fischl, who quickly recognized the benefits of the drug and pushed for its fast-track approval. If not the “magic bullet” that people were hoping for—AZT was a powerful drug with equally powerful side effects—it was something, and it opened the door for more drugs, new treatments and, finally, some hope.

Buoyed by their colleague’s success with AZT, Scott and O’Sullivan decided they wanted to treat their patients with the drug. It was a gutsy choice, particularly for O’Sullivan, who was overstepping years of opposition to pharmacologic treatment for pregnant women and potentially risking two lives with the experimental drug.

The pioneering work of Fischl, Scott, and O’Sullivan, which dovetailed with advances in testing and prenatal care, has reduced the rate of perinatal transmission of AIDS from 25 to 30 percent of all births to less than 2 percent. Through the epidemic’s peak in 1994, 20 to 30 of Scott’s patients succumbed to the disease each year; last year she lost two. “We’re working for zero,” Scott says.

This year the three physicians were honored with the Lois Pope LIFE International Research Award, bestowed annually on an internationally renowned scientist whose medical breakthroughs have led to patient applications. When accepting the award, the physicians thanked one another and they all remembered their patients. “I can’t not thank the more than 8,000 patients involved in the trials,” said Fischl. “Every single one of them made a difference, and not one of them is forgotten today.”

As the problem of pediatric AIDS becomes less prominent in this country, researchers have now started to turn their sights abroad to contain the virus’s steep climb.

CHALLENGES TODAY AND TOMORROW

The AIDS rate in Miami-Dade has dropped 60 percent from its peak in 1994, but the rate of decrease is slowing: From 59 cases per 100,000 in 2000 to 50 per 100,000 in 2002. But an even more alarming statistic shows that the rate of infection appears to be on the rise. In 1998 there were 1,733 cases of HIV/AIDS in Miami-Dade, or 79 cases per 100,000. Numbers went down in 2000. But the most recent figures from 2002 tallied 1,834 HIV cases in Miami-Dade, or 79 per 100,000—the same ratio as 1998.

In 2003 the University’s Comprehensive AIDS Program received $5 million in funding and served 6,139 patients on a regular basis. That’s a fraction of the 95,000 people in Florida living with HIV in 2002—19,766 in Miami-Dade County alone.

|

|

But the rate of infection in the United States is dwarfed by the number of people living with HIV worldwide—about 46 million, as calculated by the World Health Organization (WHO). Up to 8.5 percent of the population in sub-Saharan Africa is HIV-infected; one study at a teaching hospital in Zambia showed that one in every three women was infected.

Closer to home, the AIDS epidemic is taking an estimated 30,000 lives a year in Haiti, which has the highest per capita rate of infection in the Western Hemisphere. Political instability and a young population—about 60 percent of the population is under 24—led the WHO to conclude that “much scope exists for renewed growth in Haiti’s mainly heterosexually transmitted epidemic.”

Many of the School of Medicine’s researchers are taking the knowledge they’ve acquired locally to try to stem the epidemic abroad—“twinning” projects to strengthen the education and training of caregivers in underprivileged countries such as Haiti, Zambia, the Dominican Republic, and Kenya. While prevention, treatment, and care programs have increased in those places, the work “has gone depressingly slowly,” says Fischl. “Add infrastructure and access barriers along with a political situation, and you take two steps backwards.”

Whatever the eventual success of prevention efforts, a vaccine is critical to stopping the epidemic. Fischl and other UM researchers are studying a number of vaccines, including a therapeutic vaccine that will cycle antiretroviral therapy. “It can be done, but it’s difficult,” Fischl says. Even in the most optimistic scenarios, however, a vaccine is still several years away.

Increasing globalization spreads not only knowledge but disease. As China and India become bigger players on the international scene, they are fertile ground for a massive spread of HIV/AIDS. But intervention advocates such as McCoy believe that prevention can work, despite the mounting obstacles.

“As a human society, we can never say that we will delay approaching anything—a disease or otherwise—because it overwhelms us,” McCoy says. “As scientists, our value is to discover—whatever the challenge.”