Animals Regain Near Normal Walking Function

Miami Project Research Breakthrough

![]() iami

Project to Cure Paralysis scientists Mary Bartlett Bunge, Ph.D., and

Damien Pearse, Ph.D., announced a major breakthrough in their research

on recovering function after spinal cord injury. “These are the

best results we’ve had in 15 years,” Bunge said at a news

conference announcing the results.

iami

Project to Cure Paralysis scientists Mary Bartlett Bunge, Ph.D., and

Damien Pearse, Ph.D., announced a major breakthrough in their research

on recovering function after spinal cord injury. “These are the

best results we’ve had in 15 years,” Bunge said at a news

conference announcing the results.

The study tested an innovative treatment that

combined Schwann cell grafts with injections of cyclic AMP, a cell

messenger molecule, and Rolipram.

Cyclic AMP influences the inner workings of cells and is important

for guiding axons and their growth within inhibitory environments.

Rolipram

prevents the breakdown of cyclic AMP. The combination of the cyclic

AMP and Rolipram with the Schwann cell grafts saved axons from

dying and

resulted in more axon growth within the Schwann cells. The animals

had a 500 percent increase in nerve fibers in the graft area and

were able

to regain 70 percent of their normal walking function. In addition

to striking improvements in walking, the investigators also found

that the

combination therapy helped protect nerve fibers from dying and promoted

new growth of fibers into—as well as beyond—the area

of injury. The study was published in the June issue of the prestigious Nature

Medicine journal.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The combination therapy was designed by Bunge and Pearse with the goal of helping damaged neurons overcome inhibitory signals after injury. Once the researchers replicate these findings in other animals, they will begin to look at moving to clinical trials. “Here at The Miami Project, we are in a good position to begin to think about how we can progress to that point,” Bunge said. “This work opens up new possibilities for spinal cord-injured humans.”

Bascom

Palmer Ranked Nation’s No. 1 Eye Hospital

![]() he

University of Miami’s Bascom Palmer Eye Institute was ranked No. 1 in

the country for ophthalmology in the 15th annual survey of “America’s

Best Hospitals” published in the July 12 issue of U.S. News & World

Report. Seven other specialties at the University of Miami/Jackson Memorial

Medical Center also were ranked as among the nation’s best.

he

University of Miami’s Bascom Palmer Eye Institute was ranked No. 1 in

the country for ophthalmology in the 15th annual survey of “America’s

Best Hospitals” published in the July 12 issue of U.S. News & World

Report. Seven other specialties at the University of Miami/Jackson Memorial

Medical Center also were ranked as among the nation’s best.

“Our

clinical, educational, and research enterprises continue to grow in size,

scope, and quality, making it possible for Bascom Palmer to reflect the

world of ophthalmology in the 21st century,” says Carmen A. Puliafito,

M.D., M.B.A., chairman of Bascom Palmer Eye Institute. Bascom Palmer

has been ranked in first or second place every year the rankings have

been published.

“Our

clinical, educational, and research enterprises continue to grow in size,

scope, and quality, making it possible for Bascom Palmer to reflect the

world of ophthalmology in the 21st century,” says Carmen A. Puliafito,

M.D., M.B.A., chairman of Bascom Palmer Eye Institute. Bascom Palmer

has been ranked in first or second place every year the rankings have

been published.

The seven other UM/Jackson programs in the rankings are kidney disease (ranked No. 19); digestive disorders (23); ear, nose, and throat (26); hormonal disorders (26); urology (30); geriatrics (33); and neurology and neurosurgery (35).

University of Miami specialties moving up in the rankings this year, in addition to ophthalmology, were digestive disorders; hormonal disorders; urology; ear, nose, and throat; and kidney disease.

The standards for ranking in “Best Hospitals” are rigorous. Out of 6,012 U.S. medical centers (military and veterans’ hospitals are not included), only 177, or fewer than 1 in 30, were of high enough quality to be ranked in even a single specialty this year.

|

||

Cell biologist seeks to prevent spread of prostate cancer

Stopping a Killer

![]() ne

in six men may be diagnosed with prostate cancer in their lifetime—about

230,000 new cases in America every year. As many as half those patients

will suffer from metastasis, mostly to lymph nodes, lungs, and bones.

ne

in six men may be diagnosed with prostate cancer in their lifetime—about

230,000 new cases in America every year. As many as half those patients

will suffer from metastasis, mostly to lymph nodes, lungs, and bones.

Many of them will die.

“I’ve been interested in bone metastasis in prostate cancer, because localized prostate cancer can ultimately be cured,” says Bal Lokeshwar, Ph.D. “But bone metastasis is very dangerous.”

Lokeshwar is a cell biologist in the Department of Urology at the School of Medicine. “One of the reasons metastasis happens is because cancer cells are able to excrete enzymes, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which enable the cells to make holes through blood vessels,” he explains. “They then travel to create metastasis in vital organs such as lung, liver, and bones.”

Intrigued, he attended a conference on clinical applications for MMP inhibitors and found what he was looking for—in the form of a dentist.

Lorne M. Golub, D.M.D., M.Sc., is a dental researcher at the State University of New York at Stony Brook and a pioneer in the use of MMP inhibitors to fight diseases of the teeth, gums, and bone. He agreed to help.

At UM, Lokeshwar and Marie Selzer, B.Sc., a senior research associate, tested several MMP inhibitors. They identified a chemically modified tetracycline, called COL-3, which worked against metastasis and didn’t appear to have the side effects of tetracycline.

In laboratory experiments, they found that COL-3 greatly reduced the spread of prostate cancer and shrank tumors that had spread to the bones.

Several phase II clinical trials are now under way around the country testing COL-3 to treat cancers of the prostate and other organs, including AIDS-induced Kaposi’s Sarcoma, a debilitating skin cancer.

Innovative Community Primary

Care Center Awarded

“We’re very excited about the opportunity of really beginning to change to some degree the model of primary care that’s been around for the last 30 years or so. The 15-minute office visit, to my mind, is an outmoded way of practicing health care,” said Robert Schwartz, M.D., professor and chair of the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, at the news conference announcing the grant. |

Study shows promise for Pediatric Cancer Patients

Saving Hearts and Lives

![]() n

recent years, great strides have been made in treating children with

cancer, but the treatment that keeps them alive can have deadly consequences:

a vastly increased risk of cardiac damage. Steven E. Lipshultz, M.D.,

professor and chair of the Department of Pediatrics at the School of

Medicine, was the lead author of a study recently published in The

New England Journal of Medicine that could help children diagnosed

with cancer avoid potentially fatal cardiac problems caused by their

treatment.

n

recent years, great strides have been made in treating children with

cancer, but the treatment that keeps them alive can have deadly consequences:

a vastly increased risk of cardiac damage. Steven E. Lipshultz, M.D.,

professor and chair of the Department of Pediatrics at the School of

Medicine, was the lead author of a study recently published in The

New England Journal of Medicine that could help children diagnosed

with cancer avoid potentially fatal cardiac problems caused by their

treatment.

|

||

|

||

Of the 250,000 survivors of childhood cancer in the nation, more than 50 percent were treated with doxorubicin (Adriamycin®) or another anthracycline, a form of chemotherapy known to cause heart damage. But doxorubicin is the most effective therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the most common malignancy in pediatric cancer patients.

In the study, half of the patients in the multicenter, randomized, controlled trial, conducted out of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, were treated using the standard multi-agent protocol for ALL, which includes doxorubicin. The other half were treated with an infusion of dexrazoxane, 30 minutes before receiving doxorubicin. Dexrazoxane is a free-radical scavenger that has been found to protect the heart of adults receiving the same type of chemotherapy.

“The dexrazoxane therapy was associated with a large and statistically significant reduction in heart damage in the children who received it before their chemotherapy,” says Lipshultz. “Receiving the dexrazoxane had no impact on the effectiveness of the chemotherapy in the short term; longer follow-up will determine the influence of dexrazoxane on survival and heart function.”

The potential benefit for the treatment of childhood cancer is enormous: an estimated one in 570 young adults ages 20-34 will be a cancer survivor by the year 2010. The new protocol may help them to live even longer.

| New MRI is First in South

Florida Most human diagnostic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) systems operate with a magnetic field of 1.5-tesla. The most powerful diagnostic systems are 3-tesla—MR Services in the Department of Radiology has one. On the eighth floor of the Batchelor Children’s Research Institute, the University recently installed a 4.7-tesla research magnet—the only one in South Florida. “It allows researchers to look at structures of any part of the body,” says Daniel Armstrong, Ph.D., director of the Mailman Center for Child Development. This tool gives scientists greater precision. For example, it can monitor blood flow to the brain in real time. It also allows researchers to study progress in an experimental model, actually tracking the body’s response to a treatment—another first. Five research protocols are already cued up to use the new tool, all investigating stroke and the central nervous system, and there are many other potential uses. The purchase was made possible by a grant from the Health Resources and Services Administration within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, with operational support provided by the School of Medicine, the Departments of Neurology, Radiology, and Pediatrics, and The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis. |

Multisensory Therapy Studied to Treat Brain-Injured Children

Therapeutic Stimulation

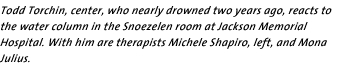

![]() n

established treatment philosophy is being put to a new use as part

of a yearlong research project in the Departments of Surgery and Pediatrics.

Under the direction of neurotrauma researcher Gillian Hotz, Ph.D.,

and John Kuluz, M.D., co-director of the Pediatric Rehabilitation Unit,

the multisensory Snoezelen room at Jackson Memorial’s rehabilitation

center is being used to treat children with brain injuries. The room

is equipped with a leaf hammock chair floating in the air, a plastic

tube filled with colored bubbles, fiber optic colored cables, and other

innovative devices designed to stimulate the senses.

n

established treatment philosophy is being put to a new use as part

of a yearlong research project in the Departments of Surgery and Pediatrics.

Under the direction of neurotrauma researcher Gillian Hotz, Ph.D.,

and John Kuluz, M.D., co-director of the Pediatric Rehabilitation Unit,

the multisensory Snoezelen room at Jackson Memorial’s rehabilitation

center is being used to treat children with brain injuries. The room

is equipped with a leaf hammock chair floating in the air, a plastic

tube filled with colored bubbles, fiber optic colored cables, and other

innovative devices designed to stimulate the senses.

|

||

|

||

The Snoezelen philosophy, developed in the Netherlands in the 1970s, has proven that surroundings can have a profound effect on behavior. In thousands of such rooms worldwide, research has shown the therapy helps autistic children, elderly dementia patients, and other nonresponsive patients begin to communicate. But little research has been done with brain-injured children.

As part of a one-year grant from the Florida Brain and Spinal Cord Injury program, at least 20 brain-injured children will receive treatment in the Snoezelen room. Early findings presented by Hotz at the international Snoezelen meeting in Israel in May showed measurable behavior changes in previously unresponsive children.

“Through controlled multisensory stimulation we hope to elicit responses from children involved in a car accident or a near drowning—any sort of traumatic brain injury event,” explains Hotz. “These are children who are severely brain damaged, comatose, or in minimally conscious states. We are definitely encouraged by what we are seeing so far.”

Nine-year-old Tavarious Williams was injured in a car accident and was reacting very little to his environment before visiting the Snoezelen room. “He can now follow things with his eyes, makes sounds, and even moves his head back and forth. We’ve seen a big improvement,” says Hotz.

The entire team was trained by experts from Beit Issie Shapiro, a center for children with disabilities in Israel that uses Snoezelen techniques. In collaboration with these experts, Hotz is hoping to make the UM/Jackson room the U.S. training site for Snoezelen therapy.

Kuluz estimates the room will be used to treat 50 to 70 brain-injured children in the coming year. “This is the first clinical trial to use the Snoezelen room with severely brain-injured children,” he says. “We’re hoping to show that this form of therapy can reach these children who are otherwise unresponsive.”

‘Local Legend’ Improves Women’s Health

![]() arilyn

Glassberg Csete, M.D. ’85, assistant professor of medicine, was

recently selected as a Local Legends award winner from the state of

Florida for her commitment and innovation in the field of pulmonology,

as well as for her contribution to the positive image of women in medicine.

arilyn

Glassberg Csete, M.D. ’85, assistant professor of medicine, was

recently selected as a Local Legends award winner from the state of

Florida for her commitment and innovation in the field of pulmonology,

as well as for her contribution to the positive image of women in medicine.

The Local Legends project was created by the American Medical Women’s Association and the National Library of Medicine. All members of Congress were asked to participate by nominating up to three women physicians from their state deserving of special recognition for their outstanding contributions to medicine. Florida Senator Bob Graham and Representative Lincoln Diaz-Balart nominated Glassberg for the award.

In his nomination letter, Diaz-Balart said: “Her pioneering research and dedication to her medical craft has helped give hope to her patients. She is a leading researcher of lung disorders, especially those ailing women.”

|

||

Physical Therapy Now a Freestanding Department

On Their Own

![]() he

Division of Physical Therapy, part of the Department of Orthopaedics and

Rehabilitation since 1986, is now officially

its own

department at the School of Medicine. Sherrill Hayes, Ph.D., P.T., who

has headed the division since 1985, is now chair of the new department.

The structural shift was approved by the University Faculty Senate in March.

he

Division of Physical Therapy, part of the Department of Orthopaedics and

Rehabilitation since 1986, is now officially

its own

department at the School of Medicine. Sherrill Hayes, Ph.D., P.T., who

has headed the division since 1985, is now chair of the new department.

The structural shift was approved by the University Faculty Senate in March.

“Since physical therapy bridges so many medical specialties, we believe that becoming a department will allow us to work in a more collaborative way across the full spectrum of all clinical departments at the School of Medicine,” says Hayes. “While physical therapists are certainly involved in treating patients with musculoskeletal problems like hip fractures and spinal disorders, we also treat patients with problems relating to the neuromuscular, cardiopulmonary, and wound care systems.”

The primary mission of the Department of Physical Therapy has always been education and research, with the overriding goal of preparing individuals for the clinical practice of physical therapy while preparing others for teaching and conducting research. The department offers two degrees; the entry-level professional Doctor of Physical Therapy (D.P.T.) program and the Ph.D. program. The educational component has been ranked among the top 10 out of 228 graduate physical therapy programs in U.S. News & World Report for the last ten years.

“We started out in 1986 with one-and-a-half faculty members and only 18 students; we now have 12 full-time faculty members, five part-time, and more than 100 graduate students,” says Hayes. “We have the highest pass rate on the national licensure exam in the state of Florida (96 percent).”

Making Eyes Young Again

![]() o

need for reading glasses as you age? No more cataracts? That may be hard

to imagine, but a new procedure being

developed at Bascom

Palmer

Eye

Institute could one day revolutionize cataract surgery and make aging eyes

young again. The treatment involves replacing the contents of the eye’s

lens with a soft polymer.

o

need for reading glasses as you age? No more cataracts? That may be hard

to imagine, but a new procedure being

developed at Bascom

Palmer

Eye

Institute could one day revolutionize cataract surgery and make aging eyes

young again. The treatment involves replacing the contents of the eye’s

lens with a soft polymer.

“This procedure goes beyond the relief from

clouding provided by traditional cataract procedures—instead it

restores the eye’s ability to

quickly shift focus at different distances,” says Jean-Marie Parel,

Ph.D., research associate professor at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute and

head of the team collaborating in an international scientific initiative

to develop the treatment. “It also offers further applications

to restore younger, 40- to 55-year-old patients’ ability to rapidly

shift focus at varying distances, while ensuring they never develop cataracts

as they age.”

“This procedure goes beyond the relief from

clouding provided by traditional cataract procedures—instead it

restores the eye’s ability to

quickly shift focus at different distances,” says Jean-Marie Parel,

Ph.D., research associate professor at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute and

head of the team collaborating in an international scientific initiative

to develop the treatment. “It also offers further applications

to restore younger, 40- to 55-year-old patients’ ability to rapidly

shift focus at varying distances, while ensuring they never develop cataracts

as they age.”

The polymer gel reproduces the characteristics of a young adult’s lens. Scientists at the Australian government’s multinational Vision Cooperative Research Center are developing the gel, while Parel’s team is perfecting the surgical techniques. Initially, researchers expect the technology will be used in cataract surgery.

Parel will present the latest findings at the joint meeting of the American Academy of Ophthalmology and European Society of Ophthalmology being held in October in New Orleans. He hopes to begin human testing as early as next year.

Photography by Donna Victor, Pyramid Photographics, John Zillioux, Patrick Farrell/The Miami Herald, Illustration byAlicia Beulow

The Center of Excellence will introduce aggressive patient and community

population screening to identify at-risk people, help them with risk

reduction activities, and provide the medical care necessary to treat

their condition and prevent long-term complications. Additional clinical

and support staff will work together to create a new approach to

primary care medicine.

The Center of Excellence will introduce aggressive patient and community

population screening to identify at-risk people, help them with risk

reduction activities, and provide the medical care necessary to treat

their condition and prevent long-term complications. Additional clinical

and support staff will work together to create a new approach to

primary care medicine.  “The MR will let us see the chemical makeup of tissue, visualize

spinal cord circuitry, or see what happens to the brain after stroke,” says

Armstrong.

“The MR will let us see the chemical makeup of tissue, visualize

spinal cord circuitry, or see what happens to the brain after stroke,” says

Armstrong.