|

|

|

He

Knew He Was In Trouble

He

Knew He Was In Trouble

![]() our hours away, in Waco, Erik Olufsen

was being rushed to an emergency room.

our hours away, in Waco, Erik Olufsen

was being rushed to an emergency room.

It was a warm spring night, a few days before Erik’s 19th birthday, and he had gone to a party with his friends. There were a lot of people there, drinking and dancing—a typical college party. Then Erik did something that was not so typical for him. As he was leaving, he decided to show off by dancing on the railing of the stairs.

When he slipped, the fall was not far, but his head landed at an angle that shattered one of his cervical vertebrae. He was unconscious for just a short time, and when he came to, he wasn’t in any pain. So there was no sense of urgency or panic.

“Come on, Erik, get up,” his friends said. And then he realized he couldn’t move.

Everything slowed down for Erik, moving in and out of focus as the shock of his injury began to overtake his body. He recalls bits and pieces of the first few hours. “Here is something odd that I remember from that night—I was wearing a new pair of shorts, and I remember that they [emergency medics] asked me if they could cut them off. I was surprised by that question considering my situation, and I thought it was very nice of them to ask. The thought crossed my mind to say no, these are brand new shorts, but I knew I was in some serious trouble and told them yes. I also remember telling them not to throw out the shorts, because I had a big $7 in my wallet.”

Shock and Horror

![]() he first indication of Erik’s condition

came when Jane walked into the hospital and saw dozens of college students

praying on the floor

of the waiting room. It was not the most comforting sign. “I

stepped over all of them and went into the emergency room,” she

recalls.

he first indication of Erik’s condition

came when Jane walked into the hospital and saw dozens of college students

praying on the floor

of the waiting room. It was not the most comforting sign. “I

stepped over all of them and went into the emergency room,” she

recalls.

When she reached her son, it took all her strength not to panic. She hadn’t been able to tell how seriously he was hurt from the phone calls she had made. She was hoping—planning—that Erik’s injuries were not as bad as they sounded. Then she saw him.

“Physically, Erik looked the same as ever. He was still in the body that was normal just hours earlier. But he was laid out like he was dead, completely motionless,” Jane recalls. “From his shoulders to his heels, he was cemented to the bed. When I touched him, he was dead weight.

“All the apparatus attached to him looked like a sci-fi movie or a movie about a torture chamber. He was so scared. How would you feel if you were at a friend’s house and then within an hour you are paralyzed with all kinds of equipment hooked up to you, people in your room crying, and a priest praying over you?

“If I fell apart, that would scare him even more. I had to find one little thing to make it better—so I did not cry when I was in the ICU with him.”

While his mother was driving to Waco, physicians had been busy trying to figure out the extent of Erik’s injuries. His fall had shattered the sixth of seven cervical vertebrae, more commonly referred to as C6. According to Edelle Field-Fote, Ph.D., associate professor of physical therapy and a principal investigator at The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis, it’s the location of one’s injury that determines whether the arms and legs or only the legs will lose function.

The American Spinal Injury Association defines five categories of spinal cord injuries, ranging from A, in which there is no sensation or movement below the level of injury, to ASIA-E individuals, who have apparently normal motor and sensory function. Immediately after an injury, though, spinal shock makes the category of injury hard to determine. All the reflexes below the level of injury are gone for several weeks to several months. Usually the return of reflexes below the level of injury marks the end of spinal shock, and this is when it is determined whether the individual has a complete or incomplete injury. An incomplete injury means that some feelings and movement may come back.

By

the time Jane had arrived at the hospital, the physicians had located

Erik’s

injury and were ready to stabilize it, but there was no way of knowing

how bad it would turn out to be.

By

the time Jane had arrived at the hospital, the physicians had located

Erik’s

injury and were ready to stabilize it, but there was no way of knowing

how bad it would turn out to be.

Once, He Knew

Where He Was Going

![]() rik

seemed an unlikely person to end up in this situation. He was thoughtful,

mature, and responsible, his

parents said, and he knew

where he was going

in life. “I had my heart and life right on schedule,” Erik

says.

rik

seemed an unlikely person to end up in this situation. He was thoughtful,

mature, and responsible, his

parents said, and he knew

where he was going

in life. “I had my heart and life right on schedule,” Erik

says.

In the aviation science program at Baylor University, Erik had enough credits to be nearly one year ahead of his class. With ten more hours of flight time (about two weeks of training), he would have his flight instructor license and would start teaching new students how to fly. Then he had “a bad night. And it’s been a long hangover,” he says.

Erik hates to talk about how he was injured. But he goes over and over that night and wonders how it happened. “Every day I get up and I see my wheelchair,” he says. “It’s a reminder of my stupidity.”

As it turns out, he is a typical traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) case—a young intoxicated man who injured a middle cervical vertebrae in a fall. Different databases cite different statistics, but it’s estimated that the incidence of traumatic SCI in the United States falls somewhere between 30 and 60 cases per million population, more than 11,000 new cases each year. The National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center Database, which has been tracking spinal cord injuries since 1973, says that motor vehicle accidents are the major cause of SCI in the United States (38.6 percent), followed by falls (23.2 percent), violence (22.5 percent), and sports injuries (6.7 percent). Since 2000, 78.2 percent of all spinal cord injuries have occurred in males.

Aftershocks

![]() hree days after the accident, Erik underwent

surgery while still completely paralyzed. As the spinal shock wore off,

Erik began regaining feeling

and movement fairly quickly. He became convinced that this was only

a temporary

state, that

maybe he would be in a wheelchair for a year and then he’d

be better. His parents felt the same way. “How do they know

he won’t get better?” Jane

remembers thinking.

hree days after the accident, Erik underwent

surgery while still completely paralyzed. As the spinal shock wore off,

Erik began regaining feeling

and movement fairly quickly. He became convinced that this was only

a temporary

state, that

maybe he would be in a wheelchair for a year and then he’d

be better. His parents felt the same way. “How do they know

he won’t get better?” Jane

remembers thinking.

The new reality of Erik’s life did not even set in as the doctors and therapists went over his daily needs and requirements, the details of SCI that few outside the field are aware of.

Before he was injured, Erik, like the overwhelming majority of adults, didn’t think much about going to the bathroom. But one of the typical aftereffects of spinal cord injury is that nerve impulses from the bladder and the bowels can no longer get to and from the brain. Erik was not released from the hospital until his mother could prove that she could catheterize her son and transfer his then-6-foot-1-inch frame from chair to bed without a crane (Jane is 5 feet 4 inches).

She wondered how she was going to bathe him and shampoo his hair. “The sponge bath just wasn’t going to cut it.” She figured out different systems herself, such as covering every metal part of the wheelchair with trash bags and using a garden hose and ice tea pitcher to wash Erik down in the backyard of their Houston home. “I hated that,” Erik recalls. It was a few months before they negotiated a shower.

Where before Erik filled his days with flying, sports, and other activities after he finished classes, there were now endless hours that he had to fill with … something. He conducted his own SCI research into treatments and techniques, leading him to participate in two clinical trials in Houston. Jane also became a self-taught expert, not only well-versed in the literature, but also criss-crossing the country using plane tickets provided to her pilot husband to attend SCI lectures, conferences, and fundraisers.

Jane heard Barth Green, M.D., professor and chairman of the Department of Neurological Surgery and founder of The Miami Project, speak at one of those conferences. Green has been unequivocal in his belief that the time has come for a breakthrough in SCI research: “Our laboratories continue to produce significant advances in the field. These are important pieces of the puzzle for The Miami Project and our efforts to find a cure for paralysis. We feel each step represents real hope for moving our science closer to the clinic,” says Green. “Since we started nearly 20 years ago, I have seen small steps turn to strides and that fuels my enthusiasm that we are getting closer each day to our goal of finding a cure.”

Jane and Erik then read about the breakthrough The Miami Project announced last summer of a new triple-combination strategy that enabled injured mice to regain up to 70 percent of their walking ability. And when The Miami Project announced it was recruiting volunteers for a clinical study run by Field-Fote beginning in January, Erik and Jane loaded up their car and moved to Miami for three months.

Do the Locomotion

![]() ne

critical component of recovery after SCI is rehabilitation. Now in the

third year of a five-year study titled “Comparison

of Locomotor Training Techniques for Individuals with Chronic Incomplete

Spinal Cord Injury,” Field-Fote

is investigating several different training studies to see if

one technique may have a better outcome in helping patients walk. Thirty-four

SCI individuals from

across the country have come to Miami to take part in these studies,

the largest of which will be completed in 2007.

ne

critical component of recovery after SCI is rehabilitation. Now in the

third year of a five-year study titled “Comparison

of Locomotor Training Techniques for Individuals with Chronic Incomplete

Spinal Cord Injury,” Field-Fote

is investigating several different training studies to see if

one technique may have a better outcome in helping patients walk. Thirty-four

SCI individuals from

across the country have come to Miami to take part in these studies,

the largest of which will be completed in 2007.

![]()

Field-Fote examined Erik and determined that four years after his injury he is “ASIA-C, which means he has some sensation and he has some movement, but the majority of the muscles below the level of injury are not able to move against gravity. ”

By ASIA standards, Erik is also considered to have tetraplegia, a term that is interchangeable with—but has replaced—quadriplegia. “All four extremities are affected to varying degrees depending on the severity, ” explains Field-Fote. Erik’s injury also causes strong spasms, which have been somewhat mitigated by a pump implanted in his stomach that constantly releases a stream of an antispasmodic medication into his bloodstream.

Here is what Erik can and cannot do: He has movement in his arms, but no fine motor skills due to loss of control of his hands and fingers. He can stand. He can take a few steps with braces on his legs, but the spasms overtake his mobility to the point that he needs the wheelchair for transportation. He can feel, but he can’t feel hot or cold. He can dress himself, but he has trouble pulling on his socks. He can use a pen, but he can’t open a can of soda or put a plug into an outlet.

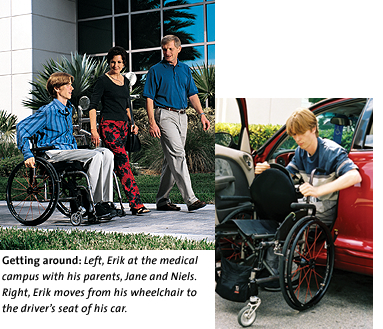

He graduated from college on schedule but has had to give up his dream of being a pilot. He can drive, but he had to lie in a ditch for close to an hour after a car accident until someone could help him move. “People say, even though you’re disabled, you can do anything if you put your mind to it. But you can’t,” says Jane. Erik cannot even become an air traffic controller because the medication that suppresses his spasms is banned by the FAA.

In Field-Fote’s study, four groups are undergoing different training techniques, all of which incorporate the use of partial body weight support to relieve some of the weight on the legs. “One of the groups is training on the treadmill with one therapist moving each leg,” Field-Fote says. “The other group is training on the treadmill with stimulation to move their legs. Another group is training on the treadmill with the robot to move their legs. And the fourth group is training overground with stimulators on their legs. We call them treadmill manual, treadmill stim, robot, and overground.”

Erik has been assigned to the treadmill manual group. To say it is a struggle for him to walk is an understatement. His attempts to walk are a battle, his long thin legs like Don Quixote’s lances tilting at windmills. He throws his entire body into the fight, using every ounce of effort, every weapon he has. It’s not pretty. And it’s not enough.

Over the course of an hour, Erik’s trainers use their physical strength

to try to get his feet to move when he walks. The training stops when his feet

just won’t land straight or a spasm comes over him, and then restarts when

he has rested a bit. He does this five days a week.

Over the course of an hour, Erik’s trainers use their physical strength

to try to get his feet to move when he walks. The training stops when his feet

just won’t land straight or a spasm comes over him, and then restarts when

he has rested a bit. He does this five days a week.

Just as he focused on his flight training before he was injured, Erik has now redirected his energy to overcoming his disability. But SCI patients must be so much more vigilant and attuned to their body’s weaknesses than the non-injured are. One day, Erik arrives with an abrasion on his leg. As he was exercising the night before, his leg was rubbing against the side of the wheelchair but he never felt it. And under a thick thatch of strawberry blond hair on the back of Erik’s head is a saucer-sized bald spot, caused by a pressure sore a few weeks after his injury. It is a common mode of injury for SCI patients, and these injuries can quickly deteriorate into life-threatening conditions.

Spinal Cord Injury Research Advances

![]() hen actor Christopher Reeve was paralyzed

in a horseback riding accident, the plight of those with SCIs was illuminated

for

many people. His

high public profile

enabled him to draw unprecedented attention and funds for SCI

research, including the work at The Miami Project.

hen actor Christopher Reeve was paralyzed

in a horseback riding accident, the plight of those with SCIs was illuminated

for

many people. His

high public profile

enabled him to draw unprecedented attention and funds for SCI

research, including the work at The Miami Project.

At the same time of the increased focus on SCI came significant advances in the field. Researchers now believe that a cure for paralysis is coming—and soon. But it’s going to take a lot more money and a lot more research. A combination of basic research discoveries together with new surgical techniques, new rehabilitation strategies, and new pharmaceuticals will be the only way to heal the multitude of damages suffered in a spinal cord injury.

The vast majority of these patients will not get better on their own. There have been some miraculous recoveries from spinal cord injuries, but most patients won’t see miracles—they need medicine. Clinical research and advances in the field are now enabling patients to live longer, avoid many of the complications that were life threatening, and regain some normality in their lives.

“These are exciting times in the area of spinal cord injury research, and recent discoveries in the area of axonal regeneration will greatly aid in the translation of experimental findings into the clinic,” says W. Dalton Dietrich III, Ph.D., professor of neurological surgery, neurology, and cell biology and anatomy, and scientific director of The Miami Project.

In the five years since their son was injured, Erik’s parents have become fervent supporters of research and more and more convinced that a cure is coming. “I feel that SCI research is like a wheel, with spokes coming out in all directions, and The Miami Project is the center of the wheel,” says Erik’s father, Niels. “If a cure is going to come, it’s going to come out of here.” Erik’s mother Jane is also sure that the cure will come. Gazing unseeingly at the glass doors through which Erik can be glimpsed being helped into a wheelchair after a spasm, she sighs and says, “I just want this to end.”

As for Erik, he plans on applying to graduate school in business because his first and second career plans are on hold. “I was very passionate about what I was doing, and there’s not a lot that I’m really into now. I haven’t found the next thing to go for,” Erik says. “I liked what I was doing before. I had a pretty exciting life.”

Erik is still the conscientious, good-natured young man he was before his accident, so he is going to work hard at recovering function. He does not want to wallow in the past, and he doesn’t want to complain about his plight. And he still feels he’s going to get better, but “I spent the first three years convinced I was going to walk. Now I don’t put a time frame on it.”

Postscript: In August 2005 Erik began working as a flight dispatcher for Continental Express Airline.