|

|

|

|

||

|

||

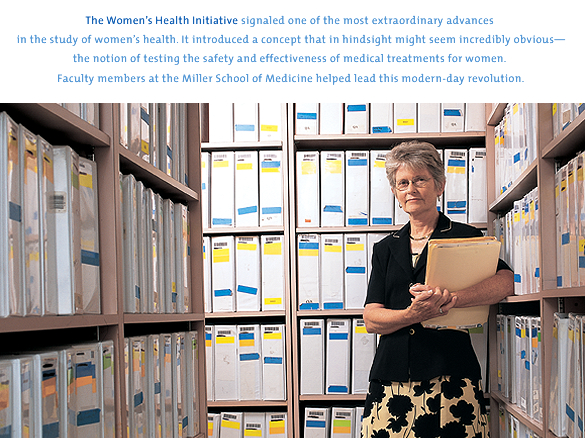

“The Women’s Health Initiative is responsible for a true revolution in how physicians care for women,” says University of Miami President Donna E. Shalala, who was secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services when the study started. “In the past, medical treatments were routinely prescribed for women that had never been clinically tested for safety and effectiveness in women, as historically women were excluded from medical research.”

The Women’s Health Initiative was made up of three clinical trials: the hormone program, the dietary study, and the calcium/vitamin D program. In addition, thousands of other women joined the observational study, which looked at health problems not studied in the clinical trials and provided a comparison group to help researchers better understand the clinical trials.

The University of Miami Leonard M. Miller School of Medicine was one of 40 WHI sites across the country. In total, close to 3,000 South Florida women participated and made their mark on medical history.

Over the years, early results from the WHI made headlines across the country and around the world, particularly in the hormone trials. When the study began, doctors believed that hormone replacement therapy protected postmenopausal women from heart disease. A woman’s chance of having a heart attack increases with age after menopause, making heart disease the leading cause of death in women overall.

“Women were being prescribed estrogen to treat menopause, and these women were observed to have a lower incidence of heart attacks and heart-related deaths, and add to that the fact that women don’t get heart disease until after menopause, and everyone assumed there was a connection,” remembers Maureen Lowery, M.D., professor of medicine and a Miller School of Medicine cardiologist who specializes in women with heart disease. “These beliefs came strictly from observational studies and were not based on scientific proof, and many physicians just started putting their postmenopausal patients on estrogen long term to protect their hearts.”

But that would all change abruptly in the summer of 2002. WHI researchers reached the stunning conclusion that estrogen plus progestin hormone treatment actually increased the risk for several life-threatening diseases: heart attacks, breast cancer, strokes, and blood clots. The women were told to stop their study pills. Almost two years later, the estrogen-alone part of the hormone trial also was stopped. This time early findings showed that estrogen alone did not prevent heart disease, but did increase the risk of stroke.

“The most important finding to come out of the WHI is that estrogen does not prevent cardiovascular disease,” says Mary Jo O’Sullivan, M.D., principal investigator of the WHI and professor emeritus in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. “Now it’s true that the risk decreased over time, about two years, but too many women died before you got to that point.”

The positive findings from the two hormone trials—fewer hip fractures and less endometrial or uterine and colorectal cancers—did not outweigh the risks.

Hormones are now used mainly for their original purpose: to treat the symptoms of menopause. “What the WHI showed us is that for women who are symptomatic, who cannot relieve their menopause symptoms in any other way, short-term estrogen therapy is appropriate,” O’Sullivan says. “Short term in my mind would be about six months.”

Seldom in the history of medicine has a single study had such an impact on medical practice. The study had an impact on its participants, too.

“I enjoyed not only what I learned, I enjoyed all of the people I met in the study,” says 74-year-old Marjorie Wessel, Ed.D., a longtime educator in the Miami-Dade public schools and a study participant from the beginning. “It was something I felt I was doing not necessarily to help us but to help our daughters and granddaughters, and it’s coming to pass now.”

Seventy-four-year-old Beverly Krakauer of Hollywood had similar feelings. She joined the initiative in the second year and was assigned to the dietary study.

“I was following a pretty healthy diet already, but I still can’t get over how much I learned—I made even further changes to my diet that I follow to this day,” says Krakauer.

The extension study of the Women’s Health Initiative will continue through 2010, with participants filling out a health form once a year. There are still many answers to come for women everywhere.