In 1952 the first medical school class was enrolled at the University of Miami. Unbeknownst to those involved, one of the most exciting and ambitious experiments of medical education and research was born. In an environment where issues of the journals Science, Nature, and The New England Journal of Medicine were as rare as snowflakes, the first accredited medical school in Florida was up to a substantial challenge. Step by step, the pioneers achieved critical milestones, and 20 years after opening the University of Miami School of Medicine was ready for a major rise.

Under the leadership of Edward W. D. Norton, M.D., the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute was founded. Traditionally, major private medical schools in the United States were usually created as a result of a substantial gift from a visionary philanthropist, which endowed the school and, in particular, established a major medical library. No such gift had endowed Florida’s new medical school. Dr. Norton knew that and figured out that in the domain of vision, a discipline whose relevance in South Florida was emphasized by the intensity of sunlight, patients would always be plentiful. There was an opportunity to create a bastion of education and research supported not only by philanthropy, but also by the profits of a very successful practice. Under its strong not-for-profit foundation and helped by the revenues from its top-notch clinicians, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute thrived.

Members of Bascom Palmer proudly measured their success not only relative to their national peers, but also against other medical school disciplines and faculty. The institute created the “Bascom Palmer brand” with no intent to co-brand the School of Medicine. The experiment turned out to be successful and Bascom Palmer Eye Institute rapidly received national and international recognition and rose through the ranks to become the top eye institute in the United States and probably the world. Members of Bascom Palmer proudly measured their success not only relative to their national peers, but also against other medical school disciplines and faculty. The institute created the “Bascom Palmer brand” with no intent to co-brand the School of Medicine. The experiment turned out to be successful and Bascom Palmer Eye Institute rapidly received national and international recognition and rose through the ranks to become the top eye institute in the United States and probably the world.

Still, success did not escape other units of the medical school. The Diabetes Research Institute Foundation, supported by the parents of children with type 1 diabetes, established ambitious research plans within the Miller School of Medicine. A powerful foundation, the DRIF united with the medical school to build a new facility and recruit a leading investigator, Camillo Ricordi, M.D., who took the helm of the institute and placed a strong focus on cell therapy for type 1 diabetes. Notably, the gestalt of Dr. Ricordi was extraordinarily collaborative with the rest of the School of Medicine and peers around the world, even while funding to DRI was exclusively to support research in type 1 diabetes.

Around the campus there are other examples of collaborative success, including in other centers created to advance research in child health. The Mailman Center for Child Development and its Debbie School, the Batchelor Children’s Research Institute, and Holtz Children’s Hospital ushered in a new era of health care for children under the leadership of Steven Lipshultz, M.D., chair of the Department of Pediatrics.

To help UM better treat cancer patients, Harcourt Sylvester Jr. and the Sylvester family provided a substantial gift with an endowment to establish the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center. Under the leadership of Jerry Goodwin, M.D., and former Dean John Clarkson, M.D., Sylvester expanded exponentially, both as a treatment center and as a beacon for biomedical research. The center has contributed significant resources to support cancer research and has collaborated with other departments at UM as well as outside entities.This novel approach to forging interdisciplinary collaborations was instrumental to the growth and success of Sylvester.

Barth Green, M.D., an extraordinarily talented UM neurosurgeon interested in the management of patients with spinal cord injury, watched Dr. Norton’s success with Bascom Palmer Eye Institute and decided to undertake a similar experiment. With the support of Dean Bernard J. Fogel, M.D., Dr. Green went on to create The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis. A year or so after the inauguration of The Project in 1985, Marc Buoniconti was the victim of a dreadful football accident. His father, Nick Buoniconti, a formidable football champion with the Miami Dolphins and a Fortune 500 entrepreneur, decided to join the “Barth Green team” and create the Buoniconti Fund, a not-for-profit organization whose fundraising would exclusively support The Project. Several years later, with a major gift from philanthropist Lois Pope, the Lois Pope LIFE Center was built and became the home of The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis and its many talented scientists and clinicians. For the School of Medicine, an important difference between The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis and Bascom Palmer Eye Institute is that the former was substantially more integrated within UM and the medical school than the latter.

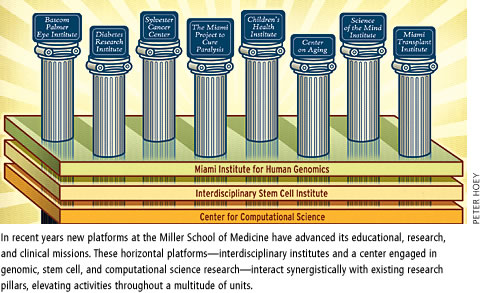

In 2004 the University announced the historic $100 million gift from the Leonard M. Miller family to the School of Medicine, which was renamed the University of Miami Leonard M. Miller School of Medicine. This remarkable gift provided the opportunity to create an entirely new platform for the organization of research and education across the school in a way that was inspired by the Sylvester Cancer Center.

As an example, instead of a research enterprise focused on a specific disease type or organ that was exclusive to the rest of the school, the Miami Institute for Human Genomics was created with the recruitment of a major center from the Research Triangle in North Carolina, the Duke Center for Human Genetics. (The Miami Institute was recently supported by an unprecedented economic development grant from the State of Florida—$80 million dedicated by Governor Charlie Crist—and pioneering funding from the Dr. John T. Macdonald Foundation.)

The goal of this horizontal platform was to bridge existing research pillars such as the Diabetes Research Institute, Sylvester, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, and The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis. It was also designed to bridge departments across the school involved in cutting-edge research. By bringing new technologies and education to a multitude of departments, divisions, centers, and institutes, the Miami Institute for Human Genomics markedly elevated research across the entire Miller School. Under the leadership of Peggy Vance, Ph.D., and Jeff Vance, Ph.D., M.D., the institute rapidly became a catalyst for collaborations and groundbreaking accomplishments.

The Interdisciplinary Stem Cell Institute was also created to bring cell therapy to various disciplines. With the recruitment of Joshua Hare, M.D., from The Johns Hopkins University, the institute elevated tissue repair for treatment of patients with chronic illnesses to a new level.

In addition to the development of centers and institutes in a horizontal plane that connects the various research pillars erected in South Florida, the medical school has also engaged in resourcing investigators more extensively than in the past. Richard Bookman, Ph.D., executive dean for research at the Miller School, has established a series of infrastructure systems such as the Clinical Research Initiation Services (CRIS) and Velos eResearch, a comprehensive clinical research management information system that enriches clinical research opportunities. Provost Thomas J. LeBlanc, Ph.D., has created the Center for Computational Science, which substantially expands the opportunity for access to informatics across the entire University. Led by Nicholas Tsinoremas, Ph.D., the center is highly integrated within the Miller School and is a tremendous asset to other horizontal and vertical platforms across the organization.

Hence, 56 years after the inception of the School of Medicine at the University of Miami, a new model of medical education and academic medicine was born. Such a model allowed for the creation of pipelines of research across campus, integrating the overarching research and education infrastructure.

These new pipelines also cover long distances, linking the Miller School to places beyond Miami. For example, we have created a new campus for the Miller School at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton, which has enrolled 32 new students each year for the past three years and has provided them with an education matching the quality of that offered on the Miller School Miami campus, but with an increased emphasis on chronic illnesses and their management. The new campus has been a formidable catalyst for “academization” of medicine in the South Florida region, with the first allopathic medicine post-graduate education program in Palm Beach County. With this experiment as a background, the Miller School is now considering additional campus opportunities even farther away from the main campus (Global Health). Furthermore, the opportunities to establish research institutes away from the campus—in locales such as Latin America—but with full-scale integration with the school’s horizontal platforms are being evaluated by the leadership of the Miller School.

Importantly, all discoveries developed by Miller School of Medicine faculty have the opportunity to be translated into commercial or industrial venues. The UM Innovation program, created by Bart Chernow, M.D., offers great expertise in technology transfer and other licensing opportunities for UM investigators.

As part of UM Innovation, the University is building a Life Science Park, an idea that UM President Donna E. Shalala brought to Miami. A former U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services, Shalala knows health care and has a keen sense of the importance of technology and bioeconomy for the country. After all, it was under her leadership that Francis Collins, M.D., Ph.D., was recruited in 1993 to be the director of the National Human Genome Research Institute at the National Institutes of Health (he stepped down in August).

Miami, with its location at the tip of the Florida peninsula—in the middle of the ocean and between four continents—turned out to be a strategic ingredient of our global role. It has always been an international city where most of its citizens are born abroad rather than in the United States. The multilingual character of Miami’s population also offers the opportunity for the city to become an important broker in the international landscape. With its central location, Miami has been blessed by the intellectual input and cultural heritage of countries in Latin America, the Caribbean, and beyond. Miami and South Florida, a central point in the corridor for exchange between North America, the Caribbean, and the rest of Latin America, will see a major growth of financial and commercial activity, including a major focus on bioeconomy.

The creation of the Life Science Park on the east side of the Miller School of Medicine campus is designed to promote the University of Miami as a catalyst for a transcontinental bioeconomy. It is also designed to foster synergy between investigators at the University and other research venues of South Florida, including Florida International University, Scripps Florida, Max Planck Institute of Florida, and other institutes that are currently in the planning stages. The Life Science Park will be able to house companies relocating to Miami and satellite operations of major international institutions interested in relocating in the United States. As part of the University of Miami plan, the creation of institutes abroad, particularly in Latin America, offers the opportunity to rapidly expand our international reputation and helps create pipelines for talented researchers and experienced staff to populate our Life Science Park.

As a result of the creation of the Life Science Park, multiple high-paying jobs will be generated, new patents and new companies will be created, and the entire surrounding community will feel the opportunities created by our venture—another bold step in our mission of collaboration and integration.

|

|

|