![]()

Project Medishare Provides Dose of 'Real-Life' for Participants

![]() hrongs

of people stand in the heat, outside the mayor's office in Thomonde,

Haiti, divided into lines according to what ails them-rashes,

lumps, bumps, worms, fever, cough. Many have walked for hours,

some shoeless over rough terrain, to see the dokte and get medical

care. For some, it is the first time in their lives they have

been treated by a health care provider.

hrongs

of people stand in the heat, outside the mayor's office in Thomonde,

Haiti, divided into lines according to what ails them-rashes,

lumps, bumps, worms, fever, cough. Many have walked for hours,

some shoeless over rough terrain, to see the dokte and get medical

care. For some, it is the first time in their lives they have

been treated by a health care provider.

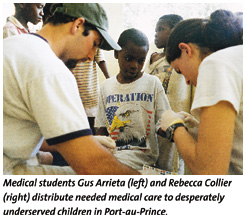

It is also a first for many members of Project Medishare, the University of Miami School of Medicine's affiliated organization created to provide medicine and health care in areas of Haiti that are desperately underserved. The program enables practicing physicians, health care workers, and students from the United States to help their colleagues in Haiti upgrade that country's health care system by working with the national medical and nursing schools, private hospitals, and state-run hospitals.

Barth Green, M.D., chairman of the Department of Neurological Surgery, conceived the idea for Project Medishare in 1994. To start the project, he sought the help and involvement of Arthur Fournier, M.D., associate dean for community health affairs and professor and vice chairman of the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health at the School of Medicine. Dr. Fournier, in turn, approached Michel Dodard, M.D., a native Haitian and clinical assistant professor in the Department of Family Medicine, and now medical director of the Jefferson Reaves Senior Health Center in Overtown.

"It was one of those things that as soon as you heard about it, you wanted to be involved," says Dr. Fournier. "I don't think any of us hesitated."

Under

the direction of Drs. Fournier and Dodard, about 600 medical

students have visited Haiti in the last four years, experiencing

medicine and the human condition in a way that would be nearly

impossible in the United States.

Under

the direction of Drs. Fournier and Dodard, about 600 medical

students have visited Haiti in the last four years, experiencing

medicine and the human condition in a way that would be nearly

impossible in the United States.

"The beauty of this program is that students don't even realize they are learning. Yet as soon as we arrive, they learn how to organize, problem-solve, overcome diversity, and collaborate," Dodard says. "This experience could never be duplicated in a classroom. It's like a medical Outward Bound experience."

About four trips are scheduled each year. Each trip lasts

about a week and includes either Dr. Fournier or Dr. Dodard,

or both, and about 12 to 15 students. The teams also are joined

frequently by other Haitian and non-Haitian faculty. Students

raise money to cover their airfare, food, and lodging. University

faculty and private physicians, Jackson Memorial Hospital, and

other community organizations donate most of the medical supplies

and medications. Once in Haiti, students and doctors stay in

either the guest quarters of a hospital, in hotels where discounts

were obtained, or in the homes of colleagues they have met from

previous visits. The mayor's office in Thomonde, a small town

where a large number of patients are cared for, also has served

as sleeping quarters for

participants.

Besides teaching good medicine, the trips tug at almost every emotion, says second-year medical student Thomas Heffernan, who was brought to tears upon his return to Miami following his first trip.

"Within my first moments back, I just started to cry. I looked around and here I was back in air conditioning with electricity and running water," says Heffernan, a student coordinator for Project Medishare. "You're so busy there and so consumed with work you don't really have time to reflect. Once home, it really hit me that I was able to leave, but all these people had to stay. "

Experiences like Heffernan's are what make these trips so invaluable, says Dr. Dodard.

"Project Medishare is real life," says Dr. Dodard. "It's a classroom without walls, and we, as mentors, are able to find so many teaching moments. It is a clear model of old-fashioned apprenticeships."

Additionally, students are able to see and treat conditions and diseases that they may have never encountered in the United States, such as leprosy and elephantiasis. But even more eye-opening is seeing other health problems that are easily preventable and treatable, such as diarrhea, malnutrition, tuberculosis, and worms.

Besides the country's impoverished infrastructure and problems with sanitation, much of Haiti's public health problem stems from people needing health education.

"We make it a point to conduct health education classes in the villages to teach things such as not drinking dirty water and showing them how to make a porridge with lots of protein for children," Fournier says. "We even try to explain how important it is for a village to do things like getting together and draining standing water to prevent malaria."

Once the education portion is completed, the students-in collaboration with the local government, organizations, and hospitals-organize "health fairs." Following the model of health fairs pioneered by the School of Medicine, students check blood pressures, provide glucose screenings, and administer vaccines. Students, through the guidance of doctors, also answer patients' questions and provide care. Hundreds of patients are seen daily. On one day a record 600 individuals were cared for.

Since the inception of Project Medishare about four years ago, a close relationship has been established with several Haitian orphanages. Often, this is where the most heart-breaking scenes take place, says Dr. Dodard. But, it also is where Project Medishare can make the biggest difference.

"On one of my trips I treated a seven-year-old dying of gastroenteritis. When I examined him, I thought there was no hope. I sent him to the hospital in Port-au-Prince and prescribed treatment for him," says Dr. Dodard. "Six months later, though, I received a photograph of a perfectly healthy boy playing soccer. It's these things that make you want to return."

Rudolph Eberwain, M.D., now an intern at the University of

Miami/

Jackson Memorial Medical Center and originally from Haiti, has

been involved with Project Medishare for three years. Besides

helping those in his native land, he believes the program also

offers

doctors in the United States another

perspective.

"I like that students go to Haiti and they come back with so much respect for the country and its people," says Dr. Eberwain. "They learn its history, religion, folklore, and culture, as well as receiving an incredible clinical experience."

The trips are a life-altering experience, says Heffernan. "I truly think that anyone who goes will come back a better person, and certainly a better physician," he says.

-Danielle Beck

![]()

University Physicians Bring Family Medicine to Haiti

![]() he

School of Medicine's Department of Family Medicine and Community

Health is making strides to improve Haiti's health care system,

an effort jumpstarted by a $1 million challenge grant recently

awarded to the department.

he

School of Medicine's Department of Family Medicine and Community

Health is making strides to improve Haiti's health care system,

an effort jumpstarted by a $1 million challenge grant recently

awarded to the department.

Under this initiative, University of Miami family practice physicians are consulting with the Medical School of Haiti and the Ministry of Health to establish a Family Medicine Residency Training Program. The program will train Haitian medical school graduates and provide much-needed services to Haiti's rural areas.

First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton announced the grant during her Caribbean tour in November, kicking off the project in two rural hospitals in Haiti-Hospital Bienfaisance de Pignon and Hospital Justinien in CapHaitien. Also present was George Soros, international financier and philanthropist, who made the grant possible through his private foundation, the Open Society Institute (OSI).

"This initiative recognizes that the necessary training opportunities currently do not exist in Haiti, where the distribution of health professionals is skewed in favor of the metropolitan areas of Port-au-Prince, and where medical training emphasizes specialization and acute disease management," said Arthur Fournier, M.D., vice chair for community affairs for the Department of Family Medicine.

Faculty from the Department of Family Medicine are spearheading and administering the project, and the Medical School of Haiti will expand the faculty and staff of its Department of Community Health in order to oversee community-based programs. Once matching funds are secured, the project will become self-sustaining within six years.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()