BY TERESA SMITH

HE IMPOSSIBLY TINY BABIES in the Neonatal Intensive

Care Unit at the University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Medical

Center seem oblivious to all the lights and the beeping and the

tubes and the wires surrounding them as they stretch and coo

in their plastic-sealed incubators. Some of them weigh less than

two pounds. Then, as often happens, a worried mom wanders in

from the maternity floor. ![]() "I'm mad because I can't take them home with me," complains

Hazel Marota, who gave birth prematurely to twin girls. Their

hospital stay is expected to last about three months. "You

cold?" she asks little Kelly, who is shaking, then she rushes

over to check on the other twin, Kelsey.

"I'm mad because I can't take them home with me," complains

Hazel Marota, who gave birth prematurely to twin girls. Their

hospital stay is expected to last about three months. "You

cold?" she asks little Kelly, who is shaking, then she rushes

over to check on the other twin, Kelsey. ![]() Before Marota leaves the floor, she is approached by Vanessa

Booth, a case manager for UM/Jackson's Early Intervention Program.

Booth introduces herself, and the two women chat for a few minutes.

This is just the first contact. By the time Marota's babies leave

the hospital, she will have a telephone list of doctors and staff

members she can call if she or the babies need help. And probably,

like the more seasoned moms who greet and hug Booth as she passes

through the unit, she will have a new friend.

Before Marota leaves the floor, she is approached by Vanessa

Booth, a case manager for UM/Jackson's Early Intervention Program.

Booth introduces herself, and the two women chat for a few minutes.

This is just the first contact. By the time Marota's babies leave

the hospital, she will have a telephone list of doctors and staff

members she can call if she or the babies need help. And probably,

like the more seasoned moms who greet and hug Booth as she passes

through the unit, she will have a new friend.

Babies in neonatal intensive care who were born at 2.2 pounds or less are automatically enrolled in the Early Intervention Program. Started in 1973 as a research follow-up program for low-birth-weight babies, the program has expanded into a full-service clinic for some of the youngest, and neediest, of patients, who are followed and assisted from birth (or referral date) to age three. After three, the children are eligible for help from the Head Start program in the public school system.

![]() ow-birth-weight

babies are often acutely ill, and even if they're not, they may

have developmental problems that show up later on, says Charles

R. Bauer, M.D., the founder and director of the Early Intervention

Program and associate director of UM/Jackson's Division of Neonatology.

Mothers can be confused and exhausted by the range of appointments

required in the months and years ahead, which can include physical

therapy, speech therapy, and special education. The Early Intervention

Program helps babies to survive, children to thrive, and mothers

to cope.

ow-birth-weight

babies are often acutely ill, and even if they're not, they may

have developmental problems that show up later on, says Charles

R. Bauer, M.D., the founder and director of the Early Intervention

Program and associate director of UM/Jackson's Division of Neonatology.

Mothers can be confused and exhausted by the range of appointments

required in the months and years ahead, which can include physical

therapy, speech therapy, and special education. The Early Intervention

Program helps babies to survive, children to thrive, and mothers

to cope.

"We're seeing kids having tremendous difficulty with everyday life and parents worried about them. They don't know what to do. Then we enroll them in the Early Intervention Program and attempt to get them intervention services in the community. It's very rewarding, and the parents are very relieved," Bauer says.

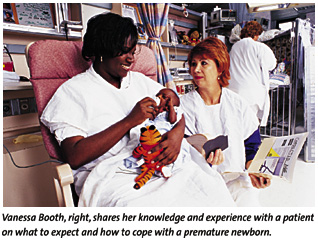

Though

infinitely grateful for the program, Vanessa Booth wishes it

had offered more counseling when her triplets were born at UM/Jackson

nine years ago. After ten years of fertility treatments, she

gave birth to three boys after 26 weeks of pregnancy. They weighed

one-and-a-half pounds each.

Though

infinitely grateful for the program, Vanessa Booth wishes it

had offered more counseling when her triplets were born at UM/Jackson

nine years ago. After ten years of fertility treatments, she

gave birth to three boys after 26 weeks of pregnancy. They weighed

one-and-a-half pounds each.

"They didn't even look like babies to me," she says. One died at two days old, and another was very sick and had to have a third of his intestines removed. He stayed in the hospital for eight months on a feeding tube. The problems, including mild cerebral palsy that eventually led to seizures, didn't end when he left. The other triplet, considered to be healthy at birth, later developed some learning disabilities.

After leaving the hospital, "I had no instructions except, 'Good luck!'" Booth recalls. She filled her days with doctor's appointments and her home with physical therapy equipment. "My house looked like a hospital," she says. It was rough, but Booth, a former teacher and lab technician, acquired a tremendous amount of knowledge and coping skills in dealing with her children's problems.

Booth decided she wanted to share her knowledge and experiences with others. "I knew what it was like to be out there alone, and I wanted to help," she says. Fortunately, just as she called Bauer to ask what she could do, the program was expanding and he was looking for someone to counsel families of children in the program. Booth fit the bill. Today, the program also has Creole-speaking and Spanish-speaking family counselors to assist the diverse patient population.

![]() orking

with families was a crucial step in the program's success, Bauer

says. "At first, we just made appointments for them. But

if the dad's in jail and the furniture's in the street and there's

no food, getting eyeglasses for the baby is lowest on the priority

list," he says. "With parent involvement, compliance

skyrocketed. It's made tremendous difference in the success rate."

orking

with families was a crucial step in the program's success, Bauer

says. "At first, we just made appointments for them. But

if the dad's in jail and the furniture's in the street and there's

no food, getting eyeglasses for the baby is lowest on the priority

list," he says. "With parent involvement, compliance

skyrocketed. It's made tremendous difference in the success rate."

In addition to the counseling parents receive at the program, social workers are dispatched to help them cope with other problems so that the family is able to give the necessary extra time and attention to the sick or disabled child.

All families entering the program have their child's and their own needs assessed in an initial interview. Some come to the program through neonatal intensive care. Others, like Jacqueline and Harry Thomas, hear of the program in the community and come in for help. The Thomases have brought their four-month-old daughter, Jessica, in for an assessment because the baby is having trouble moving her leg after being on intravenous medication due to a high fever. This problem is not unsolvable by itself, but the Thomases, who have two other toddlers at home, work the evening and night shift at the Miami Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

"It was extremely difficult," Jacqueline Thomas says. "I had to take extra maternity leave for Jessica's leg. She had surgery and skin grafts and was getting physical therapy every day. It was a nightmare." She and her husband have come in for an assessment after a night of no sleep. "There are many days like this," she says. The Early Intervention Program offers help not only for Jessica, but also for her overburdened parents.

Though it is difficult even for parents with assistance to trot their child back and forth to doctor's appointments and therapy, spotting difficulties early and starting treatment can make all the difference for these children, Bauer says. He cites deafness as an example: "People say, 'Don't worry, it'll go away.' Don't wait! Before three to six months, if you detect deafness, the child can develop almost normal speech patterns."

![]() he

Early Intervention Program began as a small research program

running on grant funds from the March of Dimes. It grew over

time as the field of neonatology grew, Bauer says. The state

began collecting data on premature babies, as other states were

starting to do, too. Florida's regional neonatal program started

about the same time as the Early Intervention Program and grew

to include research about pregnant women. Then the state began

a follow-up program, and Bauer began collecting data for a state

database.

he

Early Intervention Program began as a small research program

running on grant funds from the March of Dimes. It grew over

time as the field of neonatology grew, Bauer says. The state

began collecting data on premature babies, as other states were

starting to do, too. Florida's regional neonatal program started

about the same time as the Early Intervention Program and grew

to include research about pregnant women. Then the state began

a follow-up program, and Bauer began collecting data for a state

database.

"They were trying to find out if it was worthwhile trying

to save little tiny sick babies," he says. "It's a

very expensive system. Now it costs upwards of $40,000 or $50,000

or higher per baby, depending on how sick the baby is and what

the complications are. Is that a good investment? That was the

big question. There were debates on the TV newsmagazines 60 Minutes

and 20/20-should doctors spend the money on a one-pound baby;

are they playing God? We found most of the babies did well. They're

not all normal and they do require services, but they're well.

And they did better with early intervention. We showed pretty

quickly it's a good investment. The earlier they're diagnosed,

the better they do."

The program's staff of 43 includes four doctors, two nurses, a psychologist, case managers, data managers, and others. It's primarily a clinic now, but still plays a significant role in participating in research projects along with 14 other universities across the country. Jackson's neonatal unit in the Holtz Center for Child and Maternal Health is one of the largest in the nation. One successful experimental program involved giving mothers going into premature labor steroids before delivery to mature the babies' underdeveloped lungs, one of the main killers of premature babies. The treatment is now used widely. Program doctors also are experimenting with a drug that they hope will prevent or decrease brain hemorrhages in newborns, which can cause long-term problems such as cerebral palsy or retardation.

"We give the drug to the baby in the first hours of life in the hope of stabilizing the brain and lessening bleeding," Bauer says. The program will follow the babies over time to see how they do.

The University's Early Intervention Clinic in the Mailman Center for Child Development is very busy, open four days a week and receiving about 3,500 visits a year, some 600 of which are from new patients. Though the children are followed only until age three, many grateful parents keep up with Bauer and his staff, sending postcards and letters throughout the years.

"You really develop relationships," Bauer says. Though he no longer sees many patients, his walls are plastered with family and baby pictures from people he has helped through the program. "Now I'm getting invitations to college graduations," he says.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()