![]() n

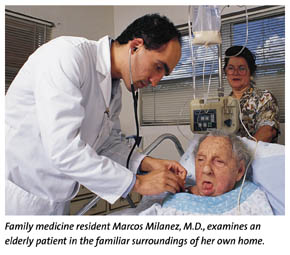

the photograph, 23-year-old Ingrid sits in bed amidst a flowered

comforter and pastel pillows. The wall behind her is adorned

with ribbon-bedecked straw hats and glamour shots of the girl

as an aspiring teenage fashion model. Finally, your eye registers

on her hospital bed and the suctioning machine beside it. Only

then do you notice the vacancy of Ingrid's stare and realize

the tremendous effort her mother has made to help her brain-injured,

quadriplegic daughter maintain her dignity and live as normally

as possible at home. Ingrid is one of a handful of South Floridians

who rely on home visits by the University of Miami School of

Medicine's third-year family practice residents for virtually

all of their health care needs. Most patients are bed-bound in

their homes due to brain injuries, Alzheimer's disease, strokes,

and a host of other chronic ailments. Rich and poor, black and

white, Hispanic and Anglo, these patients are spared the painful

ordeal of visiting a doctor's office or clinic. In exchange,

they are helping residents become more resourceful and compassionate

in their practice of medicine.

n

the photograph, 23-year-old Ingrid sits in bed amidst a flowered

comforter and pastel pillows. The wall behind her is adorned

with ribbon-bedecked straw hats and glamour shots of the girl

as an aspiring teenage fashion model. Finally, your eye registers

on her hospital bed and the suctioning machine beside it. Only

then do you notice the vacancy of Ingrid's stare and realize

the tremendous effort her mother has made to help her brain-injured,

quadriplegic daughter maintain her dignity and live as normally

as possible at home. Ingrid is one of a handful of South Floridians

who rely on home visits by the University of Miami School of

Medicine's third-year family practice residents for virtually

all of their health care needs. Most patients are bed-bound in

their homes due to brain injuries, Alzheimer's disease, strokes,

and a host of other chronic ailments. Rich and poor, black and

white, Hispanic and Anglo, these patients are spared the painful

ordeal of visiting a doctor's office or clinic. In exchange,

they are helping residents become more resourceful and compassionate

in their practice of medicine.

"This program makes residents understand that you can do the same work at home as you do in a nursing facility or hospital," says Rocio Quintero, M.D., assistant medical director of Jefferson Reaves, Sr. Health Center, where family practice residents from the School of Medicine receive outpatient training. "A chronically ill patient may be a little frightening, but as you become familiar with the person you overcome that barrier."

Equally important to these residents, as to the other School of Medicine programs that incorporate home visits, is the human element. "It humanizes you," Dr. Quintero says, "because it forces you to see the family, the person, the community, and the home--not just the chart."

Robert Schwartz, M.D., chairman and professor in the Department of Family Medicine & Community Health, likens making a house call to acting as a medical detective. During a home visit, a physician can perform a physical exam and take vital signs, as well as see how the home environment affects the patient's health.

On a house call, for example, the doctor can determine if an elderly person who has difficulty walking is being tripped by clutter, throw rugs, and stairs, or if an individual with asthma lives with shag rugs, heavy curtains, and dusty furniture. By looking in a refrigerator, a physician can get a fairly accurate impression of a person's nutritional status, while the medicine cabinet holds clues about the types and ages of medications.

![]() hough the

Family Practice Residency home visit program is the most physician-intensive--residents

go to patients' homes every two to three months but are in contact

much more often--it is one of many in which clinical expertise

is brought door to door.

hough the

Family Practice Residency home visit program is the most physician-intensive--residents

go to patients' homes every two to three months but are in contact

much more often--it is one of many in which clinical expertise

is brought door to door.

As early as their first semester in medical school, University

of Miami students make three home visits to a chronically ill

patient, then discuss their medical findings and personal observations

in small groups of students with a physician faculty member and

a psychologist or social worker.

"This puts them in a different venue than an office,

clinic, or hospital, so it creates a very different mindset for

them and the patient," says Ann Flipse, M.D., director of

the first-year clinical skills program within the Department

of Medical Education through which these visits take place. "We

expect them to learn how the patient and family live with the

disease, the patient's background, work history, and belief system

about the illness, and the patient's relationship with the health

care system. We want them to get inside their patients' lives."

Students are asked to assess patients' needs and the community resources that might meet those needs. As a result, many have acted as patient advocates, helping one chronically ill individual acquire a wheelchair, another control her intake of pain medication, and a mother of twins acquire a clinic card to have her breast cancer treated.

"I get these students at the best times in their lives, when they're susceptible to being influenced," Dr. Flipse says. "I hope that learning about this does change the way they practice medicine. So much of how a disease affects people depends on the type of people they are, the resources they have, and their support system."

That same perspective forms the basis for another home-based project--one of the studies within the National Institute on Drug Abuse research initiative by the University's Center for Treatment on Adolescent Drug Abuse (CTRADA).

The treatment approach, called Multidimensional Family Therapy, which was developed by CTRADA director Howard A. Liddle, Ed.D., a professor of psychiatry and psychology, calls on the therapist and therapeutic assistant to become aggressively involved in all aspects of the teen's life. Most of the 225 youngsters in the study are referred to the program through the juvenile justice or mental health system. Many have committed two or three crimes, are on the verge of being placed in boot camp or a residential facility, and have put their families through what Dr. Liddle terms "parental hell."

"It's not enough to talk to a kid about feelings when he has no hope of ever getting a job," Dr. Liddle says. "The approaches we use are much more practical and bring into context psychological treatment, vocational training, and tutoring programs. You're meeting with them [the teenager and family] at the home, at the school, at the kid's court hearing, arguing on their behalf. We're checking their urine for drugs and finding out if they're hanging around with gangs."

Each therapist works with four or five families, averaging three counseling sessions a week and spending time each day managing that case.

![]() t the other

end of the age scale, the University of Miami's Center on Adult

Development and Aging is one of six sites participating in a

five-year study of the benefits of providing in-home therapy

to Alzheimer's disease caregivers. Many of these caregivers suffer

psychological distress and health problems from the strain of

caring for a demented patient, yet fail to seek help because

of the difficulty in arranging alternative coverage for the patient.

t the other

end of the age scale, the University of Miami's Center on Adult

Development and Aging is one of six sites participating in a

five-year study of the benefits of providing in-home therapy

to Alzheimer's disease caregivers. Many of these caregivers suffer

psychological distress and health problems from the strain of

caring for a demented patient, yet fail to seek help because

of the difficulty in arranging alternative coverage for the patient.

The 224 caregivers participating in the study, called Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer's Caregiver Health (REACH), receive various levels of care in their home and over the phone. Some caregivers are sent to study educational materials and contacted only by phone for the 12-month study period. Another group receives one to one-and-a-half hours of weekly therapy at home for four months, followed by two months of biweekly therapy, and six months of monthly therapy. The last group receives the same services along with a special telephone to initiate family conference calls, leave messages, connect with community organizations and therapists, and participate in support groups.

The study, whose principal investigator is Carl Eisdorfer, Ph.D., M.D., professor and chairman of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavorial Sciences, also will compare how Cuban-American and Anglo-American families respond to these approaches.

"There's been a fair amount of research with spouses and adult caregivers, but almost nothing that has attempted to involve the entire family," says Mark Rubert, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and one of the study's investigators. "We're trying to look at good and bad familial relationships and maximize the family's ability to work together or, in cases where behavior is destructive, not work together."

Admittedly, the University's home-based programs are more physician- and therapist-intensive, and therefore expensive, than the prevailing health care system permits. But, from a cost-benefit standpoint, they may well make sense. As South Florida's population ages, chronic illness in the community will increase.

"Most of these people can't come to the clinic because they're not ambulatory, and it's so difficult for them to arrange transportation," says Linda Whitehead, director of administration for the Family Practice Program. "As a result, many people don't get medical care until they are so sick that they come in and fill our emergency rooms."

Geriatrics Training

Comes of Age

![]() ccording

to the U.S. Census Bureau, the nation has some 15 million residents

over the age of 65 and Florida is home to nearly a fifth of them.

As the country's population ages, the medical profession has

focused increasingly on the health concerns of seniors. Geriatrics,

a clinical specialty area dedicated to the needs of the elderly,

has become a priority in medical education--including at the

University of Miami School of Medicine.

ccording

to the U.S. Census Bureau, the nation has some 15 million residents

over the age of 65 and Florida is home to nearly a fifth of them.

As the country's population ages, the medical profession has

focused increasingly on the health concerns of seniors. Geriatrics,

a clinical specialty area dedicated to the needs of the elderly,

has become a priority in medical education--including at the

University of Miami School of Medicine.

With some 35 percent of Florida's elderly citizens living in Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach Counties, geriatric care has become an imperative for the school. First- through fourth-year students take part in training, which takes an interdisciplinary approach by combining hands-on experience with classroom instruction. Geriatrics is interwoven into the presentation of subjects such as cancer, cardiovascular health, or renal function. In fact, the medical school is considered a pioneer in geriatrics, having established a fellowship for advanced geriatric training in 1981.

"The curriculum is always changing, and geriatrics teaching has been one of the areas we've tinkered with the most," says Mark O'Connell, M.D., senior associate dean for medical education at the School of Medicine.

These refinements have not gone unnoticed. U.S. News & World Report ranked the University's geriatric program 37th in its 1999 survey of 125 teaching hospitals across the nation.

--Ruth-Ann Kimbrough