Mentors Provide Student Scientists a Lifetime of Valuable Skills

![]() raining

in biomedical science is a character-building experience. During

the approximately five years it takes to earn a Ph.D., students

take advanced courses, do a number of laboratory rotations, pass

a qualifying exam, assemble a dissertation committee, propose

and defend a research project, independently carry out the research,

and write and successfully defend their dissertation. This is

usually followed by one, and maybe two, postdoctoral fellowships

where students can further refine their scientific skills.

raining

in biomedical science is a character-building experience. During

the approximately five years it takes to earn a Ph.D., students

take advanced courses, do a number of laboratory rotations, pass

a qualifying exam, assemble a dissertation committee, propose

and defend a research project, independently carry out the research,

and write and successfully defend their dissertation. This is

usually followed by one, and maybe two, postdoctoral fellowships

where students can further refine their scientific skills.

Throughout this arduous process, the student is not alone. In contemporary scientific training, the faculty member whose laboratory the student trains in is also the student's scientific mentor. More than an advisor, the mentor develops a personal as well as professional relationship with the student, and can a play a crucial role in the student's success.

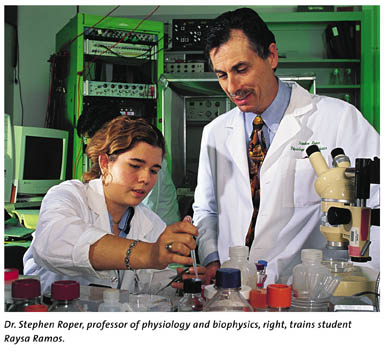

While mentors agree that their primary task is to train students in the correct way to do science, how that occurs can be as varied as the mentors themselves. Stephen Roper, Ph.D., professor in the Department of Physiology and Biophysics, takes a structured approach to mentoring. "I sit down with my trainees in the beginning and provide them with a written guide for their first eight weeks in the lab," he says. "This is designed more as a map to keep the trainees on course, rather than a hard and fast timeline, and it also documents my expectations for the student." Dr. Roper also provides an annual written evaluation for all trainees in his lab.

"In addition to teaching them to do excellent research,

I believe we must also train graduate students and postdocs to

be independent and to have thick skins," says Dr. Roper.

"The current job market is highly competitive, and we'd

be doing our trainees a disservice if we didn't prepare them

for the real world. A vital part of the training is to produce

independent scientists."

To

help teach his trainees to become independent, Dr. Roper has

them write the first draft of their own scientific papers, as

well as write their own grant proposals. "I try not to do

too much hand-holding," says Dr. Roper. "Trainees need

to experience the process, and I also want to foster in them

a sense of ownership of their papers and grants."

To

help teach his trainees to become independent, Dr. Roper has

them write the first draft of their own scientific papers, as

well as write their own grant proposals. "I try not to do

too much hand-holding," says Dr. Roper. "Trainees need

to experience the process, and I also want to foster in them

a sense of ownership of their papers and grants."

Part of what drives Dr. Roper's mentoring style is his own training experience, and one of the main virtues he tries to instill is perseverance. "There was a nine-month period during my graduate training when none of my experiments worked," he says. "Because of that, my mentor spent more time with another student in the lab whose experiments were working. That created a healthy and friendly competition between us and hardened both our resolves to succeed, which we eventually did. Now I teach my trainees not to give up too soon and to be persistent."

Rick Rotundo, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Cell Biology and Anatomy, feels that another mentoring role should be that of facilitator. "There should never be an excuse for not doing a good experiment," he says. "Part of my job is to ensure that the necessary resources are in the lab, or that we have access to them, so that my trainees can succeed."

Dr. Rotundo has trained both graduate students and postdoctoral fellows, and takes a slightly different approach with each. "Graduate training is longer than postdoctoral training, so with the graduate students I encourage more varied and independent investigation. If they initially fail, I remind them that they still have time to try again; if they succeed, there are lots of rewards."

Jason Campagna, M.D., Ph.D., completed his graduate training in 1998 in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Pharmacology under the direction of John Bixby, Ph.D. Dr. Campagna agrees that the relationship between student and mentor should be one of scientist-in-training. "At the most basic level, one needs rigorous science training: how to ask good questions and how to think through complex problems," he says. "Mentors also have to realize that although students are still learning, they should be encouraged to take initiative, have their own thoughts, and do things their own way, even if the consequences are less than optimal."

Dr. Campagna, who is currently completing his residency training in anesthesiology at Massachusetts General Hospital, also points out the "trust" factor necessary between mentor and trainee. "It is difficult putting your trust in someone, that they will guide, teach, and support you in all the right situations, and defend you in the wrong ones," he says. "Mentors who do not provide a sense of security often run into trouble getting their trainees to listen and to work.

"John and I had a unique relationship I think," Dr. Campagna adds. "He was able to sense my strengths and my weaknesses pretty easily and structure our interactions around them. We butted heads occasionally, but we always had this base in order that we could work through things."

In addition, Dr. Campagna says that mentors also are critical for at least two things: helping an otherwise bright mind learn to ask good questions that are answerable using science, and helping an otherwise bright mind to persevere when things in the lab are not working out. "Without a mentor, these two things run a big risk of getting lost. Therefore, in many ways, there is no scientist created, just a worker with a good science background," Dr. Campagna says.

For Dr. Bixby, some aspects of mentoring fall into two different categories. "There are certain aspects of training that are learned from explicit instruction: the science, writing papers, seminar presentations, grant writing, and critical reading," he says. "There are other tasks scientists perform that aren't covered by formal training, such as teaching, conducting lab meetings, running a lab, leading journal clubs, collaborating with other scientists, choosing a research question, etc. In these cases where the training is often indirect, I try to do everything as well as I can and hope my trainees learn by example."

Dr. Bixby's mentoring style is also influenced by his past experience. During the first two years of his undergraduate training, he was the only student in the lab, and received a lot of one-on-one time with his mentor. He now strives to keep his lab size small as well, so he can provide more attention to his trainees. But, he admits, "it's hard to refuse good graduate students."

Recognizing individual personalities also plays an important part in mentoring. Robert Levy, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, says that while he received some support during his graduate training, his mentor, who was a department chair, was often busy with administrative duties that precluded a lot of one-on-one time. By contrast, he says his postdoctoral training at the National Institutes of Health was a superb experience with an extraordinary scientist and individual who carried with him an inherent excitement about science. These experiences helped shape Dr. Levy's current mentoring philosophy.

"I think I'm a little more of the hands-on type," Dr. Levy says, "but I try to adjust my approach to each individual. Some trainees you give more rope and independence, and others you need to keep a little closer."

--Jeff Coulter

M.D./Ph.D. Program Coordinator

University of Miami School of Medicine