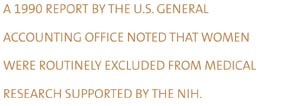

ne spring morning in 1993, cardiologist Maureen

Lowery, M.D., was at her office sifting through mail when she

came across an article on the cover of Consumer Reports

that surprised her. The article highlighted the topic of heart

disease and why women often have been neglected in the research

and subsequently the treatment of the illness. "That was

the first time I had seen anything about heart disease and women

on a front page of a layman's journal," she recalls.

An estimated 250,000 women die annually from heart disease, and with such staggering statistics, Dr. Lowery, an associate professor of cardiology at the School of Medicine, often wonders why the medical community has been so slow in treating early signs of the disease in women. Also, she questions why education has fallen short, not only for heart disease, but for other serious illnesses affecting women, such as osteoporosis.

So far, she's found one explanation in the area of heart disease--a disparity in study results comparing men and women. The majority of early research studies funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) were predominately populated by men, who were the major casualties in the coronary artery disease epidemic in the 1960s. Hence, many doctors today are working with data that represent men and heart disease, and so women are still treated based on their male counterparts, Dr. Lowery says.

One of the early studies that tracked chest pain in men and women in the early 1970s contributed to this trend. The study found that it did not matter if a man was in his fifties or sixties; once he developed chest pain, he was at risk of an impending heart attack. When researchers looked at women between the ages of 50 and 60 complaining of chest pain, they found that few had any heart attacks, partly due to a certain protection provided by the hormone estrogen, which delays the development of heart disease in women. What researchers ignored, says Dr. Lowery, was that women between the ages of 60 and 69 died as often as men after developing chest pain.

"So for the next 20 years, women would go to the doctor complaining of chest pain with the same risk factors as men, and they were told, 'It's O.K. You're emotional. Here's a Valium.' That still goes on today," says Dr. Lowery.

Even the early data on estrogen is questionable, given that most of the conclusions came from observational studies that say women who took estrogen had a 50 percent decrease in heart attacks. What these studies failed to account for were women's lifestyle and risk factors, such as obesity and smoking.

![]() 1990 report

by the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) noted that women

were routinely excluded from medical research supported by the

NIH. There are no clear-cut answers that fully explain why women

were not included in research trials, but the NIH has acknowledged

that including women in research studies adds complications,

such as concerns that an experimental treatment may adversely

affect an undetected pregnancy and that menstrual cycles could

confound results.

1990 report

by the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) noted that women

were routinely excluded from medical research supported by the

NIH. There are no clear-cut answers that fully explain why women

were not included in research trials, but the NIH has acknowledged

that including women in research studies adds complications,

such as concerns that an experimental treatment may adversely

affect an undetected pregnancy and that menstrual cycles could

confound results.

With the release of the GAO report, guidelines were strengthened to ensure inclusion of women and minorities in NIH clinical trials, and in 1993, the NIH policy became legally binding. In an effort to further address issues impacting women's health, the NIH launched the Women's Health Initiative, a multimillion-dollar, 15-year project that has been characterized as "the most definitive, far-reaching study of women's health ever undertaken."

The Women's Health Initiative is studying the most common causes of death and disability among postmenopausal women--heart disease and stroke, cancer, and osteoporosis-related fractures. The initiative attempts to address the "knowledge gap" and redress some of the inequities that exist with regard to research on women's health, according to Dr. Vivian Pinn, associate director for research on Women's Health at the NIH.

In fact, there has been a more recent study that has sorted the facts pertaining to women, heart disease, and estrogen. Known as the HERS study (Heart and Estrogen Replacement Study), this five-year nationwide effort recruited approximately 3,000 women with documented heart disease who had not had a hysterectomy and so still had a uterus. Dr. Lowery, one of the investigators in the study, says the results stunned the team of investigators nationwide.

"The women on estrogen more often died during years one and two than the women off estrogen. On year three, we started to see the increase in survival in women taking the estrogen compared to the women without it," Dr. Lowery says. "In August 1998, our research concluded that you should not start estrogen in women with pre-existing heart disease and a uterus. However, if a woman with heart disease has been on estrogen for more than two years, it was probably safe to continue, because that's when benefits begin to register."

![]() he estrogen

link also surfaces in the battle between women and the bulge.

At the University of Miami Human Performance Lab, Arlette Perry,

Ph.D., recently conducted a study on the relationship between

fat distribution and coronary risk factors in sedentary, post-menopausal

women, on and off hormone replacement therapy. She found that

post-menopausal women on hormone therapy showed a pattern of

reduced obesity on the abdomen, a reduced rate of cardiovascular

disease, and a better profile of lipids that are associated with

risk of diabetes. Generally, women who distribute weight in the

abdominal area tend to have medical problems pertaining to diabetes

risk, high cholesterol, and high blood pressure.

he estrogen

link also surfaces in the battle between women and the bulge.

At the University of Miami Human Performance Lab, Arlette Perry,

Ph.D., recently conducted a study on the relationship between

fat distribution and coronary risk factors in sedentary, post-menopausal

women, on and off hormone replacement therapy. She found that

post-menopausal women on hormone therapy showed a pattern of

reduced obesity on the abdomen, a reduced rate of cardiovascular

disease, and a better profile of lipids that are associated with

risk of diabetes. Generally, women who distribute weight in the

abdominal area tend to have medical problems pertaining to diabetes

risk, high cholesterol, and high blood pressure.

Yet, when it comes to weight control, women are pressured by the societal image that thin and slender spell success. Keeping up with this image, for many women, carries a host of problems, such as eating disorders and psychological conflicts.

"We've done some work looking at eating disorders, and there's no mystery that women who engage in sports have the highest incidence of eating disorders. They believe that the more weight they take off, the better they do in sports. That's not necessarily true," says Dr. Perry, associate professor of exercise physiology and director of the Human Performance Lab at the University. "There are medical problems with restricted food intake and excessive exercise, such as amenorrhea or lack of menstruation. When women stop having their period, they are at risk of osteoporosis, which could be a major problem in young girls."

Dr. Perry believes establishing a higher peak bone density in the young women is the key to reducing osteoporosis fractures later in life. Osteoporosis is the loss of calcium in the bones, which makes bones brittle and susceptible to fractures. The National Osteoporosis Foundation estimates that one in every five hip-fracture patients could die from complications, while one in every four will require long-term care.

When a young woman loses weight and stops menstruating due to excessive exercise or diet, her estrogen levels decline, says Silvina Levis, M.D., director of the Osteoporosis Center, which is run by the University of Miami and the Miami Veterans Administration Medical Center. Estrogen is essential in reducing bone resorption and slowing down bone loss. Up to a woman's mid- to upper thirties, bones regenerate and the process of resorption and formation of bones are at a balance. However, when estrogen levels decline, bone resorption occurs at a faster rate than bone formation.

"Yet, not all woman can take hormone replacement therapy, and not all women want to take it," Dr. Levis says. "Women, however, should engage in a discussion with their doctor about hormone therapy."

Dr. Levis advises women to become educated about osteoporosis, which is often mistaken as an inevitable consequence of aging. The reality is that osteoporosis is preventable.

"Women should incorporate foods in their diet that are rich in calcium and also exercise regularly," Dr. Levis says. "Drinking in moderation and not smoking also help to promote stronger bones."

As for heart disease and maintaining a healthy weight, exercise and moderate eating are allies. But Dr. Lowery also advises, "Modify your risk factors. Don't wait until you're 68 to stop smoking. Just don't start."

Discriminating Diseases

![]() he proof

is in the numbers. Women are particularly at risk of certain

health problems, including cardiovascular disease (heart disease,

stroke, and high blood pressure), lung cancer, breast cancer,

and osteoporosis, as the findings below illustrate:

he proof

is in the numbers. Women are particularly at risk of certain

health problems, including cardiovascular disease (heart disease,

stroke, and high blood pressure), lung cancer, breast cancer,

and osteoporosis, as the findings below illustrate:

Cardiovascular disease is the number

one cause of death among American women. Every year, an estimated

485,000 women die of the disease--more than twice the number

who die of all forms of cancer combined.

Cardiovascular disease is the number

one cause of death among American women. Every year, an estimated

485,000 women die of the disease--more than twice the number

who die of all forms of cancer combined.

- Heart disease in women often goes undetected and untreated until the disease has become severe. As a result, more women than men die of heart attack within the first year of their first heart attack--44 percent versus 27 percent.

- Lung cancer is the number one cancer killer of American women, and its rate continues to increase. More than 20 percent of women over 18 years of age are smokers, as well as 1.5 million adolescent girls.

- Breast cancer is the leading cause of death among women ages 40 to 55. One in eight women in the United States will develop breast cancer during her lifetime.

- More than 80 percent of those affected by osteoporosis--some 20 million people--are women. Osteoporosis is the major cause of disability in women over age 75.