|

||

|

|

|

|

||

“I don’t remember when we first met Janice, but she seems to have always been part of our family. I’m sure it was at a time we needed her for some of our questions without answers,” explains one Amish woman with a strong family history of manic depressive disorder.

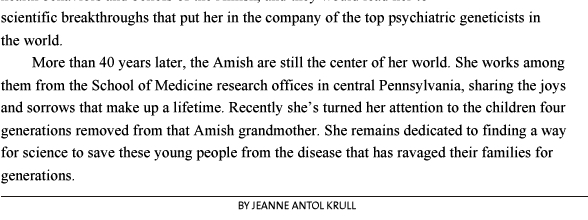

Those questions without answers are what led to Egeland’s “Genetic and Epidemiologic Study of Major Affective Disorders among the Old Order Amish” at the University of Miami. The research project has lasted almost 30 years, covered eight Amish settlements in central Pennsylvania, involved five generations of Amish families—and changed the course of psychiatric genetics forever. The two constants over the years: Janice Egeland, Ph.D., professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and professor of epidemiology and public health, and her partners in this exploration, the Old Order Amish.

![]() s

a 28-year-old Ph.D. student at Yale University, Egeland spent 1962

living with an Amish family

to research health care

patterns throughout

the community.

During that year, “they had been telling me about the mental illness

in their family and how it came down over the generations,” Egeland

remembers on a rainy autumn day, driving across central Pennsylvania,

as she has for decades, to visit several Amish families. “They

were quite convinced it was heritable, that it was ‘in the blood.’ I

was headed for a career in cancer research, but that day at the picnic

my whole life changed.”

s

a 28-year-old Ph.D. student at Yale University, Egeland spent 1962

living with an Amish family

to research health care

patterns throughout

the community.

During that year, “they had been telling me about the mental illness

in their family and how it came down over the generations,” Egeland

remembers on a rainy autumn day, driving across central Pennsylvania,

as she has for decades, to visit several Amish families. “They

were quite convinced it was heritable, that it was ‘in the blood.’ I

was headed for a career in cancer research, but that day at the picnic

my whole life changed.”

So began Egeland’s pioneering search for genetic clues to the origins of manic depressive disorder.

Manic depressive, or bipolar, disorder is characterized by episodes of mania and depression that typically recur and often become more frequent and severe during a lifetime. It’s estimated that more than 2.3 million American adults, or about 1 percent of the population, have a major mood disorder. Back in the early 1960s, psychiatry was psychosocial and psychoanalytic in nature, with little focus on possible biological reasons for psychiatric illness.

But that changed in 1969 when a book about manic depressive illness reported an association between mood disorders and two known genetic markers, for color blindness and a particular blood group located on the X chromosome. Egeland said, “I’m going to propose to do this, get funded, and use large families to replicate these markers. The perfect population is the Amish.” She had already published an extensive genealogy of Amish-Mennonite pioneer families and was well-known in the community.

|

||

Egeland is greeted warmly as she arrives at one family’s home. Even though they are just one day away from a family wedding, they are glad to make time for her visit. The father, who suffers from bipolar disorder, describes their experience: “This disease has torn our family apart. I was 17 when my mother came to me and spoke of not being able to face the day—I didn’t know what she was talking about. At the time none of us knew anything of the illness, but Janice has changed that.”

Amish families are ideal subjects for genetic studies for many reasons. Their population descends from a limited number of pioneer couples who came to America primarily in the 1700s, creating a closed gene pool. Since they are culturally cut off from the outside world, with essentially no migration into or out of the community, they can be followed over time with fewer variables that can complicate research. Amish have large families and keep extensive genealogical records on every member. They also are devoutly religious, with prohibitions against the use and abuse of alcohol and drugs, which often mask the symptoms of manic depressive disorder.

By the early 1970s, Egeland already had begun designing a study of psychiatric genetics among the Amish, and at the time she was on sabbatical from Penn State University at the University of Miami School of Medicine in the Department of Psychiatry. “The chairman then, Dr. James Sussex, told me if I could get the funding I could go north and be a ‘scholar at large.’ He said, ‘You’ll be like a new kind of ship that leaves Biscayne Bay, but instead of being from the school of oceanography, it’ll be from the Department of Psychiatry, and you’ll go up and be in a cornfield.’ That was 1974 and I’m still here.”

The connection with the Amish has lasted so long in large part because Egeland has fiercely protected their privacy and maintained strict research confidentiality. After all these years, the families were eager to talk about her as long as they weren’t identified or photographed.

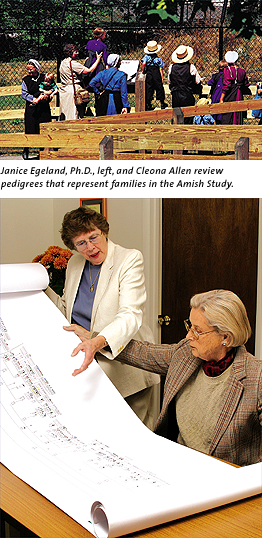

The National Institute of Mental Health funded the Amish Study from 1976 until 1994. Egeland’s goal was to localize a gene predisposing individuals to bipolar affective disorder through a genetic linkage study of multigenerational families focusing on a few markers. But the NIMH didn’t want her to stop there; it recommended that she test every known marker with blood samples from such ideal pedigrees.

“All of a sudden I was caught in something that became an incredible

leading edge for this research,” Egeland says. The first need was

to recruit a Pennsylvania-based Miami team that would grow to include

three staff psychiatrists and 14 employees

with a range of skills, including administrative, computer, even phlebotomy

expertise. The long-term staff with the program includes psychiatrist

Abram Hostetter, M.D.;

Cleona Allen, senior research associate; Susan Gravino, office manager;

and Alma Becker, phlebotomist. “We have been miles from Miami,

but we managed to coordinate it all off campus,” Egeland says.

“All of a sudden I was caught in something that became an incredible

leading edge for this research,” Egeland says. The first need was

to recruit a Pennsylvania-based Miami team that would grow to include

three staff psychiatrists and 14 employees

with a range of skills, including administrative, computer, even phlebotomy

expertise. The long-term staff with the program includes psychiatrist

Abram Hostetter, M.D.;

Cleona Allen, senior research associate; Susan Gravino, office manager;

and Alma Becker, phlebotomist. “We have been miles from Miami,

but we managed to coordinate it all off campus,” Egeland says.

![]() he research was exhaustive. The first several

years were spent delving into the community, inquiring systematically

about

any signs or symptoms

of mental

illness. The investigators conducted extensive interviews with patients

and relatives, as well as abstracting their medical records from dozens

of psychiatric

hospitals

and clinics. This produced a large sample of well-documented case materials

for subjects with various types of mental disorders. A panel of four

psychiatrists and a clinical psychologist reviewed the case records during

a rigorous

diagnostic procedure for a confirmation of bipolar disorder.

he research was exhaustive. The first several

years were spent delving into the community, inquiring systematically

about

any signs or symptoms

of mental

illness. The investigators conducted extensive interviews with patients

and relatives, as well as abstracting their medical records from dozens

of psychiatric

hospitals

and clinics. This produced a large sample of well-documented case materials

for subjects with various types of mental disorders. A panel of four

psychiatrists and a clinical psychologist reviewed the case records during

a rigorous

diagnostic procedure for a confirmation of bipolar disorder.

“You must ensure the accurate diagnosis of the disease,” Egeland says. “You can have all the blood samples you want, but if you don’t have the correct bipolar diagnosis, the rest doesn’t matter.” Only after a proper diagnosis were the blood samples drawn. In the end, the team decided to focus on five large, bipolar pedigrees in which they could see a pattern of illness over several generations. One particular family, which came to be known as Pedigree 110, eventually put Egeland on the map.

Often there was no map to follow. Egeland’s team started out testing all the conventional markers available at the time. “It was like looking for a needle in a haystack. It took us years, and we ended up being able to rule out markers, but not being able to rule in anything,” Egeland recalls. “It was just our good luck that DNA technology was coming into its own.”

Few medical schools at that time had laboratories for establishing permanent cell lines for DNA study. Strategically, the Amish Study was invited by the Coriell Institute for Medical Research to submit blood samples to the National Cell Repository, where they eventually became a resource open to the entire scientific community. In addition, a collaboration was developed among Egeland’s team, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Yale University School of Medicine. Over the years, the Amish Study created a nationwide research network that has involved six laboratories and 15 different schools of medicine. Egeland actually holds two visiting professorships: one at the University of Pennsylvania and the other at the University of Massachusetts. But Egeland, as project director, says, “We always speak in the name of the University of Miami.”

These collaborations paid off in 1987. In a study published in the journal Nature, Egeland and her colleagues reported that they found DNA markers on the short arm of chromosome 11 that predisposes individuals to bipolar affective disorders among 81 members of one large extended Amish family in Pedigree 110. This was the first time DNA technology had been used for the study of a common psychiatric disorder. “Our study defined manic depressive illness as a medical condition, not just a weakness of a person’s will. This helped begin to lift the stigma of mental illness and brought people into treatment. Psychiatric genetics received increased media attention and support in 1987,” says Egeland.

The recognition of Egeland’s breakthrough was worldwide. She became the

first woman to receive first prize from the Anna-Monika Foundation of Germany

for what it called her “brilliant investigation of a genetic foundation

of manic depressive disease.” During an international conference

on psychiatric genetics, she was singled out as one of three scientists

who achieved the biggest

breakthroughs of the 20th century.

The recognition of Egeland’s breakthrough was worldwide. She became the

first woman to receive first prize from the Anna-Monika Foundation of Germany

for what it called her “brilliant investigation of a genetic foundation

of manic depressive disease.” During an international conference

on psychiatric genetics, she was singled out as one of three scientists

who achieved the biggest

breakthroughs of the 20th century.

“What she has done is a model for how you can do scientific research and at the same time educate and care for those same people you are studying. She’s helped educate the community to the point where they understand and accept bipolar and mental illness,” says Carl Eisdorfer, Ph.D., M.D., chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. “University-wide we should be fully supportive of what’s going on up there and see her breakthrough work for what it is, an investment in human health now and in the future.”

![]() geland’s

work didn’t stop with the 1987

study. Her team extended Pedigree 110 to see if they could replicate

their findings on chromosome 11,

but that failed. A 1989 Nature publication reported the negative

findings, but detailed important methodologic issues discovered in that

two-year

period. “We

learned the importance of following all participants—the ill to

check on the course of illness and well subjects because some might have

onset with the

disorder. And we confirmed the continued importance of the correct diagnosis,” Egeland

says. “All of these things affected the results of genetic analyses

for finding markers.”

geland’s

work didn’t stop with the 1987

study. Her team extended Pedigree 110 to see if they could replicate

their findings on chromosome 11,

but that failed. A 1989 Nature publication reported the negative

findings, but detailed important methodologic issues discovered in that

two-year

period. “We

learned the importance of following all participants—the ill to

check on the course of illness and well subjects because some might have

onset with the

disorder. And we confirmed the continued importance of the correct diagnosis,” Egeland

says. “All of these things affected the results of genetic analyses

for finding markers.”

|

||

|

||

Over the past 15 years, the research has expanded to include not only the original Pedigree 110, but three additional large bipolar pedigrees. Blood samples from more than 500 individuals in these pedigrees constitute a permanent cell collection for ongoing genotyping in laboratories, particularly at the University of Massachusetts School of Medicine.

The search continues not only to locate a bipolar gene, but also to track one for autoimmune thyroid disease. In a collaborative decade-long study, J. Maxwell McKenzie, M.D., and Margita Zakarija, M.D., in the Department of Medicine have conducted detailed thyroid screens for most Amish subjects with DNA in Egeland’s pedigrees. In the process, many participants learned their depressive symptoms were actually being caused by an undiagnosed hypothyroidism, and they could then be put on proper treatment. “The discovery of a gene for either bipolar disorder or thyroid disease has an even greater potential given the latest advances in molecular biology and opportunities for novel therapeutic interventions,” says Egeland.

The Amish Study research network has continued to publish a number of pioneering articles. A 1996 article in Nature Genetics was the first to report that manic depressive disorder is inherited as a complex trait, with genetic markers identified on three chromosomes. In 1998 a publication in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reported for the first time the likelihood of a protective gene that would explain why some members of a family have bipolar disorder and others do not but could still pass the disease to their children.

Early research from the Amish

Study had indicated that “affective” type

symptoms could be documented in childhood at least 9 to 12 years before

the actual onset of the illness. This led to a recent focus by Egeland

and colleagues

on

prodromal or early symptoms of bipolarity among well children at high risk.

Early research from the Amish

Study had indicated that “affective” type

symptoms could be documented in childhood at least 9 to 12 years before

the actual onset of the illness. This led to a recent focus by Egeland

and colleagues

on

prodromal or early symptoms of bipolarity among well children at high risk.

In 1994 Egeland and colleagues from UM, Harvard, and Columbia University started the Child and Adolescent Research Evaluation (CARE) program. It is a prospective study of well Amish children that follows 100 children with a bipolar parent and 110 children of well parents. These children represent the fourth and fifth generation of families in the Amish study.

“I held these children when they were born, and I knew many of their parents as children and when they first became ill,” Egeland says. “We see these children every summer after school is over, we weigh and measure them, bring them toys, and then we conduct structured interviews with their parents about any worries or concerns.”

The histories of these children were evaluated blindly by four clinicians for ratings of risk for bipolarity. In a study published last year, Egeland’s group found that twice as many children of bipolar parents were rated at risk compared to the children of well parents in a control group. The researchers concluded that episodic predictors of the illness may appear in childhood, but could go underground until adolescence or adulthood.

“There’s no real consensus in child psychiatry about children and bipolar. Are the signs we are seeing really related to a conduct disorder or ADHD, rather than bipolar?” says Jon Shaw, M.D., director of child psychiatry at the School of Medicine and a member of the panel that evaluated the CARE children. Shaw also travels regularly to Pennsylvania to help with the clinical assessments of well children at risk. “The CARE study will give us the answers as we see which of these children go on to present later in life with the illness.”

![]() s

several of his daughters work in the kitchen preparing dinner, an Amish

man whose wife is bipolar

explains how he

sees the disease: “The first episode

of manic depression makes a wide circle, like a path in the woods—it’s

nice and smooth. With each new episode, the circle draws closer and the pathway

is less smooth. If the illness is untreated or caught late, the circling becomes

more frequent and you fall into deeper and darker ruts.” One of

his children already has symptoms of bipolarity.

s

several of his daughters work in the kitchen preparing dinner, an Amish

man whose wife is bipolar

explains how he

sees the disease: “The first episode

of manic depression makes a wide circle, like a path in the woods—it’s

nice and smooth. With each new episode, the circle draws closer and the pathway

is less smooth. If the illness is untreated or caught late, the circling becomes

more frequent and you fall into deeper and darker ruts.” One of

his children already has symptoms of bipolarity.

In the final years of her career, it is the children Egeland worries about the most. “Nothing is as important to me as finding the funding to keep the CARE and genetics program going and seeing the results so these children and their children to come can have a better life,” she says. It’s with those children in mind that Egeland is analyzing data on how the illness first appears, because that is often the key to how it will unfold over a lifetime and respond to treatment.

She says her work may never be done.

“As long as I can still stand on my two legs, I will be here for these people,” Egeland says. “I feel so lucky to have had the opportunity and support to define research objectives, gather a network of collaborators, and reach those goals. All along the way the Amish have been my partners, not my research subjects.

“The most satisfaction,” she continues, “comes from knowing people are well who might not have been, people are alive who might have committed suicide, and young people have been treated to hopefully stop the illness from becoming firmly entrenched in a cycling pattern that would keep them from having a normal life. I feel like I made a difference, somewhere, somehow in their lives. They certainly made a difference in mine.”

The gratitude flows both ways. One Amish man with extensive bipolar illness in his family expresses a sentiment felt widely in his community: “We wonder what our life would have been like if Janice hadn’t come along. To us, Janice and her life’s work are a miracle.”