|

|

|

Fournier, vice chairman of the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health

and associate dean for community health affairs at the Leonard M. Miller

School of Medicine, made his first trip to Haiti in December 1994. He made

his 100th in December 2004. Along the way, he’s taken dozens of medical

students on life-changing educational experiences, working with other UM

faculty members and the legendary Paul Farmer, M.D., the infectious disease

specialist who founded Partners in Health to serve Haitian patients free

of charge.

“Our students really are inspired down there, they’re inspired by our own faculty, they’re inspired by Dr. Farmer,” says Fournier. “They’re inspired by the courage and endurance of the Haitian people.”

Three students who made the trip in 2001 were especially inspired. With some help from their physician advisers, they diagnosed congenital rubella syndrome, which has been unheard of in developed nations since being eradicated by childhood vaccinations. Their discovery led to a chain of events resulting in the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) administering rubella vaccines to Haitian children for the first time beginning this year.

But half a dozen steps had to align just right, or none of this would have happened.

Hands-On Training

![]() edical

missions to the third world can be outstanding learning experiences,

for both faculty members and students. For the

experienced clinician, it’s

a reminder of the special gift all physicians can offer those in need,

regardless of specialty—the value of basic medical care. And students

on these trips get hands-on experience early in their medical training

in a setting that humanizes

medicine in a truly unique way.

edical

missions to the third world can be outstanding learning experiences,

for both faculty members and students. For the

experienced clinician, it’s

a reminder of the special gift all physicians can offer those in need,

regardless of specialty—the value of basic medical care. And students

on these trips get hands-on experience early in their medical training

in a setting that humanizes

medicine in a truly unique way.

The benefit to the Haitian people is obvious. Fournier adds, “I also want to inspire the next generation of doctors to aspire to the noblest parts of our profession, which is serving those in the greatest need.”

The Miller School of Medicine is one of a very few that operate at the front door of the third world and have such an established relationship. And only a handful of medical schools take first-year students beyond books into hands-on skills training, although the number is growing. “We prepare our students to be able to do a history and physical examinations in year one,” says Fournier. Before the fall of 1990, when the Miller School of Medicine began offering it to students in the class of 1994, no school did.

Alex Mechaber, M.D., F.A.C.P., now runs the clinical skills program. “I’ll get calls from preceptors who say, ‘Alex, you want me to let students do clinical exams on patients?’ Yeah, that’s right. ‘But they’re in the first semester of their first year!’ That’s right. ‘It wasn’t like that when I was in medical school.’ Yeah, that’s right.”

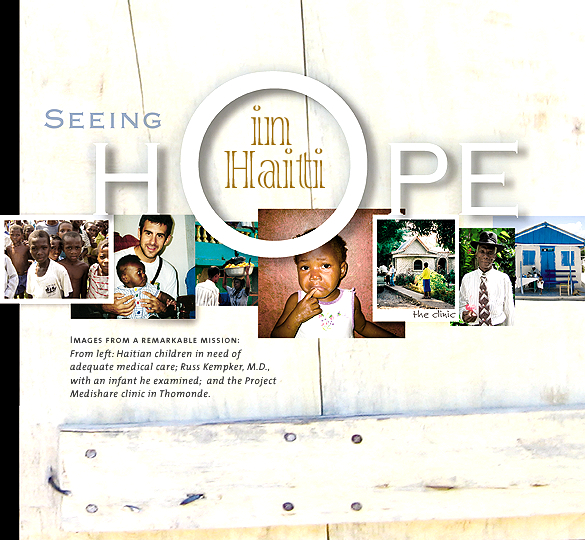

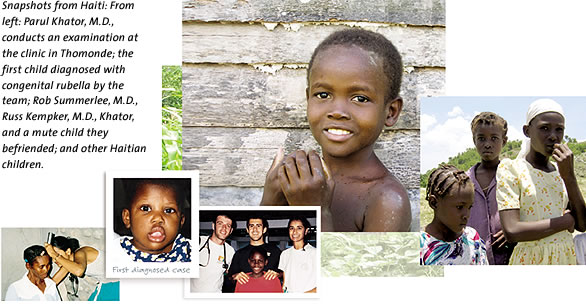

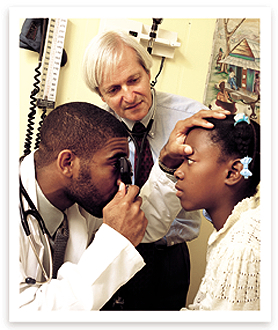

“That is probably one of the biggest assets to the UM School of Medicine, getting the chance to practice clinical skills early,” says Rob Summerlee, M.D., who joined fellow first-year medical students Russ Kempker, M.D., and Parul Khator, M.D., on the one-week medical missions in 2001.

“It really adds to the progression in your skills as a doctor. To this day, I really feel like my eye exams are the strongest part of my physical exams because of that early experience. I’m surprised more schools don’t do that—it definitely makes you a better clinician in the long run.”

A Different World

![]() ournier has made many of these trips, but he was

accompanied in March and June of 2001 by his sister-in-law, pediatrician

Nancy Golden, from

Cape Cod,

Massachusetts.

Both excursions were part of UM’s ten-year-old Project Medishare

for Haiti, founded by Fournier and Barth Green, M.D., president and clinical

program director

of The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis and chairman of the Department

of Neurological Surgery. Project Medishare collaborates with Farmer,

the Peace Corps, and others

to provide medical care to Haitians and has had a tremendous impact in

one of the poorest communities in the Western Hemisphere.

ournier has made many of these trips, but he was

accompanied in March and June of 2001 by his sister-in-law, pediatrician

Nancy Golden, from

Cape Cod,

Massachusetts.

Both excursions were part of UM’s ten-year-old Project Medishare

for Haiti, founded by Fournier and Barth Green, M.D., president and clinical

program director

of The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis and chairman of the Department

of Neurological Surgery. Project Medishare collaborates with Farmer,

the Peace Corps, and others

to provide medical care to Haitians and has had a tremendous impact in

one of the poorest communities in the Western Hemisphere.

“We work very closely with Dr. Paul Farmer in developing community health workers, so we’ve used peers as educators to get the message out,” says Fournier. “Our immunization rates in the Plateau Central, where we work, have gone from the worst in Haiti to, now, 98 percent of kids getting the prescribed package of immunizations—although the prescribed package is pretty anemic.”

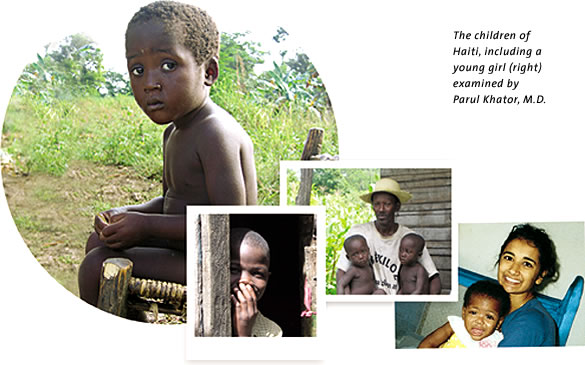

Students often see patients in established medical missions, like the one Project Medishare runs in the village of Thomonde. Occasionally, students and their mentors will venture into the countryside to other villages and orphanages. Fournier points out that most orphanages in Haiti take only healthy orphans—and because of social and medical strife, there are an estimated 187,000 such children in the nation. Only a handful of orphanages accept handicapped or abandoned children, and given the strength of the family unit in Haitian culture, it’s highly unusual for parents to give up a child.

But on this trip, the UM crew visited three orphanages with handicapped and abandoned kids.

While seeing patients on the first trip in March, Kempker made an unusual discovery.

“Russ was palpating a patient’s abdomen and found an enlarged spleen,” says Khator, now an ophthalmologist in Atlanta. She examined the girl and felt the same thing. “Then Rob came over and corroborated our finding.”

They started taking notes.

The five of them were together at dinner when an interesting question came up—something only someone trained in eye exams would know. Summerlee had actually volunteered in an ophthalmologist’s office as an undergrad.

He asked why some of the orphans had cataracts, which appear almost exclusively in older adults.

“Dr. Fournier was quiet for a long time,” says Khator.

But Golden had a question. “Did they have any other symptoms?”

All three students piped up, describing a host of unusual findings—abnormally shaped heads (microcephaly), deafness, cases of retardation, signs of autism, a heart murmur, glaucoma—and multiple children, ages 1 to 14, with cataracts.

“Congenital rubella.” Golden was thinking out loud, but her experience as a pediatrician told her they were seeing a disease that had been eradicated from the United States for more than 30 years.

|

||

|

||

Congenital rubella is relatively harmless in adults. It can cause a fever and rash for a couple of days, but rarely does permanent or life-threatening harm. In fact it doesn’t pose a significant risk even to young children. But in the early stages of pregnancy, especially the first 12 weeks, exposing an expectant woman to rubella can pose serious risks to the fetus. Exposure closer to week one poses an even higher risk than exposure at week 12.

Up to 85 percent of children exposed to rubella in that first trimester may suffer some negative impact.

“The developing fetus has no immune system and the virus gallops through and causes damage to the brain, damage to the skeleton, damage to the eyes,” says Fournier.

“It’s particularly terrible in a country like Haiti,” says Golden, “because it has such limited resources.”

In addition to the symptoms the students found, children with congenital rubella are at increased risk of meningoencephalitis, congenital heart disease, diabetes mellitus, hepatitis, hyperthyroidism, and more. There is also a sharp increase in the likelihood of a miscarriage.

The risk has been known for generations, since well before a vaccine was available. There was even a strategy to reduce it in many communities around the world.

Because rubella tended to strike in epidemics, when someone in a commun-ity contracted the illness, girls younger than childbearing age would attend “German measles parties” specifically to expose them to the virus. The girls would develop immunity before pregnancy so that when they got pregnant, their unborn child was immune to the disease.

Learning Curve

![]() fter the initial diagnosis in those children, Fournier

encouraged the students to report their discovery.

fter the initial diagnosis in those children, Fournier

encouraged the students to report their discovery.

Even in surrounding Caribbean and Latin American countries where there are vaccination programs, as many as one-third to one-half of women of childbearing age may be susceptible. In Haiti the rate is much higher. Based on reported rates in Jamaica and Trinidad, the number of children born with congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) per 1,000 births is about 1.62. In Haiti, it’s 34.

Almost every western child is vaccinated before starting school—in fact, according to the World Health Organiza-tion, the Americas have the highest vaccination rate of any WHO region, involving 38 countries and territories, with about 90 percent of 1-year-olds receiving the vaccine.

But not in Haiti.

Lifelong care for a child stricken with CRS could cost in the tens of thousands of dollars, even in a poor nation like Haiti, which was the last remaining western nation that didn’t vaccinate against CRS. Even the country’s neighbor on Hispaniola, the Dominican Republic, began rubella immunizations last year.

“This is a situation where you can make an intervention for 93 cents,” says Fournier. “It doesn’t get any better than that in prevention.”

And the discovery was made by curious and insightful first-year students.

In all, in March and June, they saw 80 children in three orphanages, and in at least six cases they identified classic symptoms of what they now knew was congenital rubella—something they had barely studied, let alone expected to find. Encouraged by Fournier, they documented the cases.

“That was my first taste of research,” says Summerlee, now practicing internal medicine in Bethesda, Maryland. “It’s very eye-opening because Dr. Fournier told us it’s really something that you’ll never see again in countries that have a vaccination campaign.” The students wrote it up and managed to get their findings accepted as a short communication in the December 2002 Public Health, the journal of PAHO.

They examined congenital rubella rates in the Caribbean and the U.S. before vaccination programs, and they estimated there are as many as 440 new cases each year in Haiti.

PAHO already oversees a program to vaccinate Haitian children for diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus, polio, and starting in 2004, measles—but not German measles. And only about half of Haitian children receive even those shots, despite the success in the area served by Project Medishare.

“In Thomonde we will have the infrastructure so that once PAHO makes the new vaccines available, we’ll be able to get almost 100 percent of the kids in this particular catchment area immunized right away,” says Fournier.

Lives Saved, Lives Changed

![]() o go through the whole intellectual process of writing

an article and getting it accepted, and then seeing that actually cascade

into an effective

intervention,” recalls

Fournier, “I think it had a really profound effect on the three

students.”

o go through the whole intellectual process of writing

an article and getting it accepted, and then seeing that actually cascade

into an effective

intervention,” recalls

Fournier, “I think it had a really profound effect on the three

students.”

“Never would I have thought that our little observations would lead to anything,” says Summerlee. “Who knows how much of a role our publication played, but just the possibility that the women and children of Haiti will benefit from it is terrific.”

“To get published was the icing on the cake,” says Khator. “To have this change in Haiti, to offer a vaccination program, that’s the cherry on the icing on the cake. I did a dance. Russ and I heard at the same time and we were thrilled. Later we saw Rob and we high-fived and hugged and everything.”

Golden, the pediatrician, is fairly matter- of-fact about the diagnoses they all made. “The students brought pieces of knowledge to the debrief, which they shared,” she recalls. “Dr. Fournier and I had been trained and brought other pieces and we were able to put it together.”

“All the stars aligned,” says Summerlee. “The students were doing all the exams, getting our practice, but Drs. Fournier and Golden were the ones that knew the science. We honestly didn’t know when we brought it up at dinner what it was.”

Family ties and her personal commitment have brought Golden to Haiti more than once. She is a big advocate of the student medical missions. “There are things they see that otherwise they would never, ever look at. You could read this in a book and memorize it for the next exam, but if you see it in the flesh then it becomes much more meaningful.”

So how formative was the trip?

“To Rob, I.D. doesn’t mean infectious disease, it means international disease,” notes Khator, who says this also helped guide her decision to specialize in eye care. As for Kempker, he’s devoting his career to infectious diseases.

“We all loved it,” says Khator. “Project Medishare, that’s such a great experience. I told everyone in the class below me, if there’s one thing you do, you have to do this.”

But what about all the puzzle pieces that had to fall into place to bring vaccinations to Haiti—did fate intervene?

“It’s probably much bigger than all of us,” says Summerlee, who is echoed by Khator. “I definitely think a lot of different forces came together to make this diagnosis possible.”

“I always feel that way, every trip,”says Fournier, walking away

to plan the next adventure. “It’s a big question mark. You just never

know what kind of help you’ll get.”

Kelly Kaufhold is a senior media relations officer and writer in the Office of Communi-cations at the Miller School of Medicine. Special thanks to Wassim Serhan for his photography. Other photos by Donna Victor and students who participated in the mission.