any physicians and health decision-makers are quite happy to let the health care system go on like this until the wheels come off,” says Laurence Gardner, M.D., F.A.C.P., vice dean of the University of Miami Leonard M. Miller School of Medicine, Kathleen and Stanley Glaser Professor, and chairman of the Department of Medicine.

“The consequences are outrageous,” says Gardner. “Primary care physicians have to increase the number of patients they see in order to generate enough income to live. As a consequence of that, the quality of primary care medicine has decreased.”

The burdens on current primary care practitioners—the reduced pay and increased patient volume—are now poisoning the next generation. An American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) study found that in just five years, from 1998 to 2003, the number of medical students choosing family medicine had dropped in half.

“Every year it gets a little more difficult,” says Penny Tenzer, M.D., director of the residency program and vice chair of the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health. “The interest in family medicine is significantly down.”

The problem is dire and growing worse. Over the next decade, as fewer students enter the field, the first Baby Boomers become eligible for Medicare, dramatically increasing both the size and age of the patient population. “The oldest patients and those with chronic conditions are going to suffer the most from the collapse of the primary care system,” says Gardner. “The older patients have no real voice in helping to change policy.”

But some physicians at the UM Miller School and elsewhere, as well as medical associations, are giving voice to those concerns.

The Problems

![]() here are three big issues weighing on primary care,

all converging into a growing crisis. First, the elderly population is

growing, precisely

the people at greatest risk for chronic illnesses.

here are three big issues weighing on primary care,

all converging into a growing crisis. First, the elderly population is

growing, precisely

the people at greatest risk for chronic illnesses.

Second: “As more high-tech procedures have entered medicine, they have been paid for out of the same pot,” says Gardner, referring to Medicare and private insurance. “The payment to primary care physicians has declined.”

An AAFP study quantifies that. In 1999 general pediatricians, on average, saw 122 patients per week for which they were paid $137,800 a year. A gastroenterologist saw 90 patients, on average, earning $299,200.

“It seems like you have to put in a lot more work for the same pay,” says third-year medical student David Lopez, who has completed a couple of primary care rotations. He is torn between internal medicine and rehabilitation medicine. “I really don’t think much about what my colleagues will make in other specialties, but it’s a reality that they’ll make more.”

Then, there is that quality-of-life issue. “We look at the residents’ life, and we think we don’t want to go through that,” says Lopez.

“Internal medicine was hectic, and the patient census was very high,” says Lisa Martinez, another third-year student, about her internal medicine clinical rotation. She hasn’t ruled out primary care, but she also wants to have a family one day. “We worked long hours, which I didn’t mind, but those rotations involved 12-hour days. That kind of schedule really makes you think about the future.”

A combination of good pay and personal altruism used to be enough to overcome some of the lifestyle negatives. But both of those are now in short supply, especially with medical students graduating with, on average, $120,000 in debt— even more for students from private medical schools.

“I think a reason a lot of the students aren’t interested is that they have presupposed ideas about what it would be like to practice primary care,” says Rosette Chakkalakal, a fourth-year medical student at the Miller School who is pursuing a primary care track in internal medicine.

“The word is glamour. Many of them think primary care is not glamorous.”

The Impact

![]() he topic people are talking about on both sides of

the reception desk in the doctor’s office is the month-long wait

for appointments.

he topic people are talking about on both sides of

the reception desk in the doctor’s office is the month-long wait

for appointments.

“In the old days pediatricians never retired, they worked until they were 70 years old or more. But with managed care they’re giving up, they’re retiring,” says Eugene R. Hershorin, M.D., a UM pediatrician. In fact, an American Medical Association report points out that one-third of American physicians are over age 55, and most of those older practitioners are expected to retire within ten years. If nothing changes over the same period, more medical students will enter specialties, fewer will choose primary care.

“At the top end they’re getting out earlier,” says

Hershorin. “In

the bottom end fewer are getting in—and they’re working

for fewer hours, so the number of doctor hours available to the

patients is

dwindling.”

“At the top end they’re getting out earlier,” says

Hershorin. “In

the bottom end fewer are getting in—and they’re working

for fewer hours, so the number of doctor hours available to the

patients is

dwindling.”

For health care professionals, the second topic on a lot of minds is pay.

“I think reimbursement is a little bit of a taboo—nobody wants to talk about it because they feel like it’s the antithesis of why they went into medicine,” says fourth-year Miller School student Amer Hanano. Students may not talk about it, but they do think about it.

Lopez says the worry among many students is that they don’t want to invest ten or 12 years of their life incurring a lot of debt, then struggle to pay their bills. “I really don’t know how the cost of my education would affect that decision,” says Lopez.

Lopez saw the real-world impact of dwindling reimbursement through his preceptor on a clinical rotation. “He said that he had more economic demands because his son was in medical school, so he was trying to make more money,” Lopez says of the internal medicine doctor he did a rotation with. “That forced him to take more calls to different hospitals. He admitted that he was trying to increase his patient volume.”

A third impact, one that’s harder to see, is that undervaluing primary care may actually increase the cost of medicine.

The ACP report, which is ominously titled “The Impending Collapse of Primary Care Medicine and Its Implications for the State of the Nation’s Health Care,” uses the illustration of an internist treating a patient with diabetes. Long-term management of blood sugar can prevent an amputation, a procedure that would cost Medicare or an insurer $30,000.

Isn’t that an investment worth making up front?

Not really. Even our own health care plan doesn’t explicitly pay for prevention,” says Gardner. “Savings by investing in prevention is not a concept that has been embraced by most parts of organized medicine.”

To be blunt, when those patients fall through the cracks of primary care and progress to where they need a specialist, the specialist gets paid—and a lot more than the referring physician.

“If we move to a health care system where people basically distribute themselves to physicians according to body part and there’s nobody conducting the orchestra, I think that would be a very frightening view of medicine,” says Tenzer. “I mean, who do you call on Saturday morning when something’s wrong if you don’t call your primary care physician?”

Often, family doctors and pediatricians are invested

in more than just medical outcomes. “For example, if a 17-year- old comes in with a

cough, then you ask whether he’s been smoking, and he says ‘Yes,’” explains

Hershorin, “then you’re thinking about how to advise him against

smoking. And you ask, ‘Is there a little more going on here?’ and

he admits to smoking dope. Well now you’re thinking about intervening

with that. While you’re doing this you’re thinking to yourself, ‘How

can I do this quickly so I can see the next patient who is dealing with

the same issue?’”

Often, family doctors and pediatricians are invested

in more than just medical outcomes. “For example, if a 17-year- old comes in with a

cough, then you ask whether he’s been smoking, and he says ‘Yes,’” explains

Hershorin, “then you’re thinking about how to advise him against

smoking. And you ask, ‘Is there a little more going on here?’ and

he admits to smoking dope. Well now you’re thinking about intervening

with that. While you’re doing this you’re thinking to yourself, ‘How

can I do this quickly so I can see the next patient who is dealing with

the same issue?’”

It’s like constant triage. Physicians used to see four patients an hour. Now it may be ten. Hershorin emphasizes that the health care can’t be compromised. But the social intervention can. “Those are the things that pediatricians may have to sacrifice to concentrate on the medical intervention.”

Even that compromised personal care will be lost if primary care fails and we move toward specialty-only medicine. Here’s the scenario. “You’re going to go to your cardiologist for chest pain, and if the cardiologist finds out that it’s not your heart, then you’re going to go to a gastroenterologist for your chest pain,” says Mark Multach, M.D., chief of the Division of General Medicine. “And when he finds out that it’s not GI, you’re going to go to a spine guy to see if it’s coming from your spine. You’re going to go doctor shopping.”

And every doctor can bill insurers for much more than the $25 or so that a primary care physician gets reimbursed. Academic medical centers, like the UM Miller School, concede some value to primary care, even if it is income generated after the referral. Right now, the general medicine doctors in practice get paid only for time spent with the patient. Making follow-up phone calls and answering weekend pages pays nothing.

“Even though I may lose $100,000 per primary care practitioner, the institution profits a million to a million-and-a-half dollars per primary care practitioner by all the secondary CAT scans, the testing, the cardiologists they see, and the sur-geries and all those things that I refer for,” says Multach, who is also the Department of Medicine’s vice chairman for clinical affairs.

The Prescription

![]() he answer is a major overhaul of the way the health

care system is organized,” says

Robert Schwartz, M.D., chairman of the Department of Family Medicine

and Community Health. “It’s complicated. It has to be taken

care of at the national level.”

he answer is a major overhaul of the way the health

care system is organized,” says

Robert Schwartz, M.D., chairman of the Department of Family Medicine

and Community Health. “It’s complicated. It has to be taken

care of at the national level.”

The ACP report calls for the creation of the “advanced medical home,” health care focused on the well-being of the whole patient. It would reward primary care doctors with pay for referrals. It also calls for a strong embrace of technology, like electronic records and e-mail access for simple and routine consults, and help for physicians to pay for it. While not everyone likes the ACP’s terminology, many primary care physicians think it’s a great idea.

After all, especially with HMO insurance plans requiring a referral, the family physician, pediatrician, and internist are the front door for patients entering the health care system. And after a patient sees a specialist, say a surgeon, he or she often returns to the primary care practice for follow-up.

Medical educators also play a role.

“As a medical educational institution, we have

responsibilities to society to produce the kind of graduates who are going

to meet society’s

needs,” says Mark O’Connell, M.D., senior associate

dean for medical education. Students aren’t forced into

primary care, but there are a couple of ways to increase exposure

to it.

“As a medical educational institution, we have

responsibilities to society to produce the kind of graduates who are going

to meet society’s

needs,” says Mark O’Connell, M.D., senior associate

dean for medical education. Students aren’t forced into

primary care, but there are a couple of ways to increase exposure

to it.

The UM Miller School, for example, was one of the first in the country to teach clinical skills to first-year students, back in 1990.

Between clinic visits and student-run health fairs, students get exposed early and often to general medicine, and the curriculum also emphasizes its importance.

“We have a lot more electives in primary care,” says Amer Hanano, the fourth-year medical student leaning toward radiology. “We have internal medicine, we have general primary care, we have family medicine, we have pediatrics, we have obstetrics and gynecology. By the time you get to your fourth year, less than 30 percent of your time can be spent in subspecialty electives.”

In fact, some students like Hanano think specialties get short-changed, but O’Connell insists it reinforces the general medical skills that all doctors need. In the end, of course, students still make the choice.

Another hurdle for people like O’Connell, who are trying to cultivate the next generation of family physicians, is the dark cloud hanging over clinical rotations in primary care. Often, students spend four weeks with doctors out in the community who have terrible morale because they are drowning under an impossible load of patients and paperwork. Investing in solutions like hiring staff or converting to electronic records—another major ACP recommendation—is impossible when they’re struggling to pay their bills.

But again, there may be solutions.

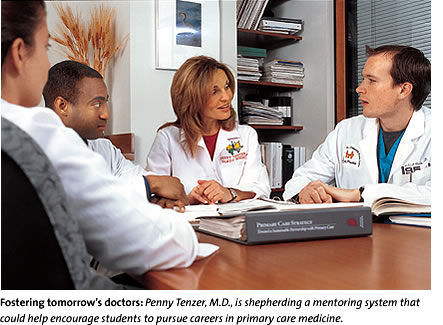

Tenzer is shepherding a multilevel mentoring system where each person in the medical education process is guided by someone one step above—for example, a resident would work with a medical student. That may help retain enthusiasm across “generations” of medical students.

“I felt that those of us who are inter-ested in primary care were rarities in my class,” says Chakkalakal. “But when you get out there and meet other primary care students around the country, it really makes you feel better.”

There are a few bright spots for students and residents. Hershorin says he can’t wait to wake up and go be a pediatrician every day, even after 27 years. And there are still students who dream of a small private practice office, treating families or kids, caring about them, being a part of their lives.

“At UM they taught me to not only be a doctor but a teacher,” says Chakkalakal. “Because if you teach your patients well enough, you don’t have to be the one to save their lives because they’ll save their lives themselves.”

The ACP report, the AAFP study, and experiences here at the Miller School also all suggest that certain people are more amenable to primary care practice to begin with, especially students from low-income or rural areas, minorities, and women.

“There are some markers of people who go into primary care,” says Tenzer, who is also president of the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors. “We need to stop discouraging people from going into it who have the heart and calling, and, in fact, should be looking for ways to recruit students with that aptitude.”

“The system has to change,” says O’Connell. “The good old days of Marcus Welby are gone.”

![]()