or much of his life, Jack Birnholz knew sooner or later his heart would

fail him. Both his parents died from heart-related conditions. His four

brothers all have had heart trouble, the oldest dying at age 53 after

his sixth heart attack. And for a time, Birnholz acquiesced to his genetic

fate. A heart attack at 41, a second at 59, followed by the implantation

of a defibrillator and a partially successful bypass surgery, led doctors

to predict his premature death due to irreversible heart disease. ![]() But Birnholz, now 70, has cheated that fate. Three years ago after being

hospitalized with congestive heart failure—an erratic beating of

the heart—doctors gave him just months to live. His only hope: a

transplant. In February 1999, following the death of a 29-year-old Orlando

man whose organs were donated to transplant recipients, surgeons at the

University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Medical Center gave Birnholz the

healthy heart he had never known. “I lived much of my life believing

that my next step could be my last,” says Birnholz, a real estate

consultant living in Aventura, Florida. “That fear is gone, and my

whole outlook on life has forever changed.”

But Birnholz, now 70, has cheated that fate. Three years ago after being

hospitalized with congestive heart failure—an erratic beating of

the heart—doctors gave him just months to live. His only hope: a

transplant. In February 1999, following the death of a 29-year-old Orlando

man whose organs were donated to transplant recipients, surgeons at the

University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Medical Center gave Birnholz the

healthy heart he had never known. “I lived much of my life believing

that my next step could be my last,” says Birnholz, a real estate

consultant living in Aventura, Florida. “That fear is gone, and my

whole outlook on life has forever changed.”

Birnholz’s testimonial is far from unique. Each year more than 20,000 people nationwide receive organ transplants. In less than a generation, transplant surgery has progressed from largely experimental to nearly routine. Lives are prolonged, dreams renewed, and quality of life immeasurably enhanced. And UM/Jackson is a major force behind this revolution in patient care. Physicians from the center’s transplant division are known worldwide as pioneers in their fields. There, new drugs and surgical procedures are routinely developed. Patients seeking treatment travel to the center from around the globe. And with close to 500 transplant operations performed annually, including some performed nowhere else in the nation, UM/Jackson ranks among the top three medical centers for organ transplantation in the United States.

M/Jackson’s

prominence within the field of transplant surgery is a product of nearly

30 years of hard work. In 1972 UM/Jackson initiated a small program in

transplantation that, at the time, may have seemed more rooted in science

fiction than in medical fact. The world’s first human heart transplant,

or graft, wasn’t achieved until 1967, in South Africa. That same

year the first successful liver transplant in the United States was done.

And indeed, the UM/Jackson program was short-lived. While many of the

surgical challenges had been overcome, the patient’s immune system

routinely attacked the new organ in the same way it might attack a harmful

bacteria or other foreign invader to the body. Survival rates were low.

A breakthrough occurred in the mid-1970s with the discovery of drugs that

could block the patient’s immune response, reducing the risk of transplant

rejection. The most effective of these at that time, cyclosporine, was

approved for commercial use in 1983. This and other immunosuppressant

drugs paved the way for widespread use of organ transplants to treat a

variety of life-threatening, or so-called “end-stage,” organ

diseases. In addition to heart transplants, surgeons were perfecting the

technique of liver, kidney, pancreas, lung, and combined heart-lung transplants.

Early research also began on other organs.

M/Jackson’s

prominence within the field of transplant surgery is a product of nearly

30 years of hard work. In 1972 UM/Jackson initiated a small program in

transplantation that, at the time, may have seemed more rooted in science

fiction than in medical fact. The world’s first human heart transplant,

or graft, wasn’t achieved until 1967, in South Africa. That same

year the first successful liver transplant in the United States was done.

And indeed, the UM/Jackson program was short-lived. While many of the

surgical challenges had been overcome, the patient’s immune system

routinely attacked the new organ in the same way it might attack a harmful

bacteria or other foreign invader to the body. Survival rates were low.

A breakthrough occurred in the mid-1970s with the discovery of drugs that

could block the patient’s immune response, reducing the risk of transplant

rejection. The most effective of these at that time, cyclosporine, was

approved for commercial use in 1983. This and other immunosuppressant

drugs paved the way for widespread use of organ transplants to treat a

variety of life-threatening, or so-called “end-stage,” organ

diseases. In addition to heart transplants, surgeons were perfecting the

technique of liver, kidney, pancreas, lung, and combined heart-lung transplants.

Early research also began on other organs.

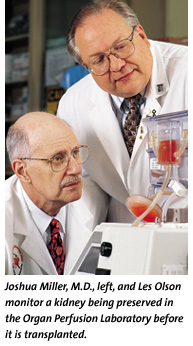

UM/Jackson

revived its transplant program in 1979. Under the direction of Joshua

Miller, M.D., the center performed 28 kidney transplants in its first

year. Since then the program has steadily grown. In 1986 its first liver

transplant was performed. A year later, surgeons here did their first

heart transplant. The program has since expanded to include pancreatic

and intestinal transplants. It also has pioneered much of the work on

removing the islets of Langerhans from the pancreas for transplantation

into diabetes patients.

UM/Jackson

revived its transplant program in 1979. Under the direction of Joshua

Miller, M.D., the center performed 28 kidney transplants in its first

year. Since then the program has steadily grown. In 1986 its first liver

transplant was performed. A year later, surgeons here did their first

heart transplant. The program has since expanded to include pancreatic

and intestinal transplants. It also has pioneered much of the work on

removing the islets of Langerhans from the pancreas for transplantation

into diabetes patients.

In 2000 the center recorded the first heart-lung transplant in South Florida. Dr. Miller, a past president of the American Society of Transplant Surgeons and now the codirector of the Division of Transplantation at the School of Medicine, attributes the program’s growth to the broader contributions to patient care made by advances in transplant science. “What we do impacts many other areas of medicine—molecular biology, cancer treatment, immune system diseases. There is so much spin-off,” says Dr. Miller.

Today UM/Jackson is one of the busiest transplant centers in the nation. Each year surgeons replace more than 150 kidneys, 200 livers, and 30 hearts. More importantly, it also is one of the most successful, with patient survivability often higher than national averages. The kidney program, with one of the highest survivability rates among all U.S. medical centers, is a good example. Dr. Miller credits the high success rate to a list of factors: improved organ removal and preservation techniques; collaboration with pharmaceutical companies developing new immunosuppressant drugs; and their unique sophisticated “immunological monitoring” systems that allow physicians to continuously determine whether the patient’s body is receiving the correct amount of postoperative medication.

Organ preservation techniques are unparalleled at the University’s Organ Procurement Organization (OPO), run by Les Olson, its founding director. Olson has significantly enhanced the integrity and effectiveness of the process, making the OPO one of the most productive procurement organizations in the United States. His tireless efforts have helped rescue thousands of organs and tissues for South Floridians and individuals throughout the nation.

Another key factor, explains Dr. Miller, is UM/Jackson’s effort at developing techniques to decrease the likelihood of organ rejection. While the use of immunosuppressants is still required, UM/Jackson researchers are experimenting with new approaches. Among the most promising involves the intravenous infusion of bone marrow from the organ donor to the recipient patient.

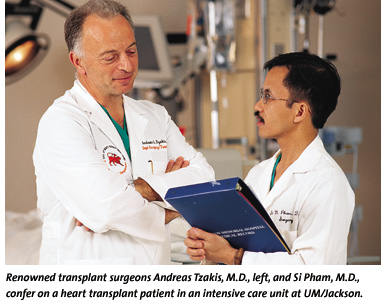

hile

UM/Jackson’s transplant division has grown steadily over the past

two decades, it was the arrival in 1994 of renowned transplant surgeon

Andreas Tzakis, M.D., that many credit with sparking its rise to greatness.

A native of Athens, Greece, Dr. Tzakis gained fame in the early 1990s

at the University of Pittsburgh, when he and a team of surgeons twice

transplanted livers from baboons into humans. Animal rights activists

decried the procedure; Dr. Tzakis called it a last-hope effort for two

dying people. (One patient survived 70 days, the other two weeks.) He

also participated in the world’s first long-term successful islet

cell transplantation and helped pioneer a technique for transplanting

the intestine.

hile

UM/Jackson’s transplant division has grown steadily over the past

two decades, it was the arrival in 1994 of renowned transplant surgeon

Andreas Tzakis, M.D., that many credit with sparking its rise to greatness.

A native of Athens, Greece, Dr. Tzakis gained fame in the early 1990s

at the University of Pittsburgh, when he and a team of surgeons twice

transplanted livers from baboons into humans. Animal rights activists

decried the procedure; Dr. Tzakis called it a last-hope effort for two

dying people. (One patient survived 70 days, the other two weeks.) He

also participated in the world’s first long-term successful islet

cell transplantation and helped pioneer a technique for transplanting

the intestine.

Dr. Tzakis, who could have written his own ticket in the high-profile world of transplant surgery, says he jumped to UM/Jackson because few medical centers could offer such a range of resources: one of the top clinical liver units in the nation, a well-established immunology lab, and a most-respected organ procurement program. He says he also was attracted by the success of UM/Jackson’s kidney transplantation program and of the adjacent Diabetes Research Institute. “It seemed like all the pieces were there,” he recalls. “The infrastructure was in place to build something very special.” Dr. Tzakis has performed more than 1,000 transplant surgeries since his arrival in 1994.

While Dr. Tzakis brought name recognition to UM/Jackson, his more lasting contribution is the creation of one of the top liver transplant programs in the nation. “This certainly has been one of our objectives,” he says. “To develop novel approaches. And innovative procedures.” For example, Dr. Tzakis’ team helped develop antiviral drugs that prevent the recurrence of Hepatitis B in liver transplant patients. Previously, the risk of recurrence was so high that transplantation was rarely prescribed for patients infected with the virus. “This is another of the challenges we’re working to overcome,” he explains. “We can do a transplant, but how do we know there won’t be a recurrence of the original disease in the new, healthy organ?”

Although he has spent much of his career developing techniques for treating patients with liver disease, Dr. Tzakis also is known worldwide for intestinal and multi-visceral (multi-organ) transplantation. Indeed, going back to his days at the University of Pittsburgh, few surgeons, if any, have performed more intestinal transplants than Dr. Tzakis. Other than the brain, the intestine is often regarded as the last frontier of transplant science. With a potent, complex immune-response system in place (to protect the body from bacteria, viruses, and other invaders humans ingest), the intestine has long defied surgeons’ attempts at transplantation. Donor organs were hopelessly overwhelmed by the body’s defense mechanisms. While problems still exist, Dr. Tzakis’ work has opened an avenue of hope for patients who equate intestinal disease with a death sentence.

Dr. Tzakis, now codirector, along with Dr. Miller, of the Division of Transplantation, sees his mandate in the broadest possible terms: to better treat all patients needing transplants, regardless of the organ or disease. To that end, he is helping to develop other organ transplant programs at UM/Jackson. The center’s program in pediatric cardiothoracic surgery, under the direction of Eliot Rosenkrantz, M.D., is regarded among the nation’s best. Earlier this year Dr. Rosenkrantz remarkably performed two heart transplants in a single day, saving the lives of two children with congenital heart defects.

n

1999 Tzakis helped to recruit one of the top cardiopulmonary surgeons,

Si Pham, M.D., from the University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Pham now performs

more than 30 heart transplants annually, including the one on Birnholz.

One year ago he performed the first heart-lung transplant in South Florida.

Dr. Pham, director of the cardiopulmonary transplantation program at UM/Jackson,

credits Drs. Tzakis and Miller with having the foresight to bring all

members of the transplantation team—surgeons, clinicians, researchers,

and support professionals—under one geographical umbrella. While

much of their work is independent, the physical proximity of offices,

labs, and operating rooms fosters interaction. “It may sound unimportant,

but this is really one of the great benefits of working at the University

of Miami,” says Dr. Pham. “There is such a great exchange of

ideas. We share research and attend each other’s conferences. That

doesn’t happen everywhere.”

n

1999 Tzakis helped to recruit one of the top cardiopulmonary surgeons,

Si Pham, M.D., from the University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Pham now performs

more than 30 heart transplants annually, including the one on Birnholz.

One year ago he performed the first heart-lung transplant in South Florida.

Dr. Pham, director of the cardiopulmonary transplantation program at UM/Jackson,

credits Drs. Tzakis and Miller with having the foresight to bring all

members of the transplantation team—surgeons, clinicians, researchers,

and support professionals—under one geographical umbrella. While

much of their work is independent, the physical proximity of offices,

labs, and operating rooms fosters interaction. “It may sound unimportant,

but this is really one of the great benefits of working at the University

of Miami,” says Dr. Pham. “There is such a great exchange of

ideas. We share research and attend each other’s conferences. That

doesn’t happen everywhere.”

Professional

camaraderie was not the only selling point for Dr. Pham. In the end, a

great transplant program requires two things that only a larger urban

center can provide: patients and donors. Miami has both. With more than

three million people, the Miami-Fort Lauderdale area has its share of

patients suffering from end-stage organ disease. It is also a bustling,

crowded place, with all-too-many victims of auto accidents, gunshots,

and other trauma injuries. Upon their death, such victims are the most

likely candidates for organ donation.

Professional

camaraderie was not the only selling point for Dr. Pham. In the end, a

great transplant program requires two things that only a larger urban

center can provide: patients and donors. Miami has both. With more than

three million people, the Miami-Fort Lauderdale area has its share of

patients suffering from end-stage organ disease. It is also a bustling,

crowded place, with all-too-many victims of auto accidents, gunshots,

and other trauma injuries. Upon their death, such victims are the most

likely candidates for organ donation.

But ironically, improved health and safety practices in recent years are creating a shortage of organ donors. A decrease in violent crime, mandatory gun locks in some states, a greater use of seatbelts, and increased awareness of drunk driving laws all have worked to reduce the rate of patients who die suddenly or who linger in a coma after a violent injury. That, coupled with significant advances in transplant surgery, has caused a widening gap between the number of organ donors and the number of patients needing a transplant.

According to figures compiled by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), a government organization that helps match donors with recipients, about 15,000 patients received transplants in 1999, leaving around 7,000 more on a waiting list for organs. By 2000, the number of transplants increased to 22,000, but requests increased to 72,000, swelling the waiting list to about 50,000. The gap continues to widen. An average of 15 people die every day waiting for organs that could have saved their lives.

“In a way we’ve become a victim of our own success,” says UNOS President Patricia Adams, M.D. “With the success and acceptance of organ transplantation, it has become routine therapy for many diseases. We have the know-how to save tens of thousands of lives. What we don’t have is enough donated organs to make it possible.”

The dilemma has spawned debate on how to best encourage organ donation. Surgeons say few hospitals respond quickly and efficiently following the death of a potential organ donor. Expediency is crucial: hearts and lungs must be transplanted within a few hours of removal from the donor’s body; livers can last up to ten hours, kidneys up to a day or two. Some argue that family members should be counseled more aggressively when a patient slips into a coma. Others propose the use of anencephalic babies—those born missing much of their brain and with little chance of survival.

But critics warn against redefining death. A need to harvest organs from the dying should never interfere with every doctor’s first rule: “do no harm.” Instead, they say, public awareness programs should target new organ donors. Hospitals should improve systems to harvest and preserve organs. Public policy also can help. Some European countries have adopted “presumed consent” laws, which allow surgeons to remove organs unless an individual specifies otherwise prior to death.

One person who supports such a law is David Adams, Ph.D. Six years ago, suffering from chronic liver disease, Adams received a liver transplant at UM/Jackson. The experience so changed his outlook on life that Dr. Adams, a psychologist in private practice most of his career, moved to Miami from his home in St. Petersburg, Florida, to work as a counselor at the UM/Jackson transplant program. “Someone else’s liver saved my life,” says Dr. Adams, now 72. “People are dying every day while waiting for organs. I’m proof that that doesn’t have to happen, and that there is life after transplantation.”

|

Miracle in Texas

Cameron was suffering from venous malformation mesentery, an abnormality of the blood vessels that causes veins to grow in a tangled mass within the abdominal organs. The condition, which he likely had since birth, caused internal bleeding and distention of the stomach. He was being fed from a feeding tube; his growth was stunted. By the time he reached age five, doctors said he could die at any moment from massive bleeding. Two previous surgeries to correct the malformation proved unsuccessful. A transplant seemed his last hope. But Dr. Tzakis, one of the world’s foremost intestinal transplant surgeons, searched for an alternative to the high-risk procedure. Intestinal transplants are uncommon because the body’s immune response is especially strong in the abdominal area, often causing rejection of the new organ. He ruled out surgical repair of the malformation, because it would be too difficult to stem blood flow from the sponge-like mass of veins. Instead, he removed most of Cameron’s intestines and pancreas and about 40 percent of his stomach. The organs were placed in chilled water to preserve them, allowing Dr. Tzakis to dissect the abnormal growth, clear obstructions and clots, and reconstruct blood flow. The organs were then implanted back into Cameron’s body. The procedure lasted 19 hours. Today Cameron is eating normally. His height and weight are up. Dr. Tzakis has found no signs of the malformation returning. Jones calls his son’s recovery a miracle. “Most of his doctors had given up hope. But Cameron cheated death,” Jones insists. “This fall he’ll be starting school for the first time. That’s something we thought we’d never have a chance to see.” Photography by The Miami Herald |

But

once in Miami, surgeons recommended yet another option: removal,

repair, and return of the original organs to the boy’s body.

The highly unusual procedure, called auto transplantation, had been

done only twice before in the world. Luckily, one of them had been

performed by Andreas Tzakis, M.D., codirector of the School of Medicine

Division of Transplantation and the man who would be treating Cameron.

“Obviously we were ready to try anything,” says the boy’s

father, Charlie Jones, from their home in Grand Saline, Texas. “Without

something really drastic, we knew he would die.”

But

once in Miami, surgeons recommended yet another option: removal,

repair, and return of the original organs to the boy’s body.

The highly unusual procedure, called auto transplantation, had been

done only twice before in the world. Luckily, one of them had been

performed by Andreas Tzakis, M.D., codirector of the School of Medicine

Division of Transplantation and the man who would be treating Cameron.

“Obviously we were ready to try anything,” says the boy’s

father, Charlie Jones, from their home in Grand Saline, Texas. “Without

something really drastic, we knew he would die.”