DISCOVERY YIELDS CLUES TO FIGHTING VIRUSES

Curbing Cancer

![]() eatriz

Fontoura, Ph.D., has discovered an important step in fixing the damage

caused by viruses—a step that moves researchers closer to understanding

one of the mechanisms of cancer and how to treat the disease.

eatriz

Fontoura, Ph.D., has discovered an important step in fixing the damage

caused by viruses—a step that moves researchers closer to understanding

one of the mechanisms of cancer and how to treat the disease.

|

||

Working with a protein that is involved in some types of leukemia, Fontoura and her colleagues discovered a key piece of information about viral infection. A virus interferes with the cell’s genetic program by binding with a type of protein nicknamed a “nup,” or nuclear pore complex protein, and halting the flow of molecular information to and from the nucleus of the cell.

The team found that interferon, a molecule that is released by the body to defend against viral attack, can be used to increase the cell’s production of “nup” proteins and overcome this block in the flow of information.

“It’s almost as though the virus stopped all the trucks that were used for transport and then interferon stimulated the production of more trucks,” says Richard J. Bookman, Ph.D., associate dean for graduate studies at the School of Medicine. “Previously we didn’t know that you could overcome the virus in this way.”

“This is a key cellular regulatory step,” says Fontoura, who collaborated on this research with 1999 Nobel Prize winner Günter Blobel of The Rockefeller University. “It might have important impact for other viruses.”

Interferon, which interferes with the division of cancer cells and can slow tumor growth, is used to treat several kinds of cancer, hepatitis, and other diseases.

Fontoura’s work is funded partly by the Florida Biomedical Research Program. The program uses proceeds from the 1997 settlement of Florida’s lawsuit against the tobacco companies to support biomedical research on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of tobacco-related diseases, such as cancer.

“Dr. Fontoura is our most recent recruit,” says James D. Potter, Ph.D., professor and chairman of the Department of Molecular and Cellular Pharmacology and codirector of the school’s Executive Office of Research Leadership, “and this is a crowning achievement for her to have her first paper as a University of Miami faculty member published in Science, one of the top research journals.” Fontoura joined UM as an assistant professor last year from The Rockefeller University, where she was a postdoctoral associate at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

![]() magine

being so tired you can’t even walk across a room. Then imagine feeling

that way all the time, and you’ll know how it feels to suffer from

chronic fatigue syndrome. This debilitating condition is characterized

by fatigue that lasts for more than six months and has no known cause.

It also has no known cure; currently the most physicians can do is treat

prevailing symptoms, when possible, with medication. But Barry Hurwitz,

Ph.D., and Nancy Klimas, M.D. ’80, professors at the University of

Miami’s Behavioral Medicine Research Center, are investigating a

potential remedy. Working with them are researchers in the Department

of Medicine’s Allergy and Infectious Diseases Clinic.

magine

being so tired you can’t even walk across a room. Then imagine feeling

that way all the time, and you’ll know how it feels to suffer from

chronic fatigue syndrome. This debilitating condition is characterized

by fatigue that lasts for more than six months and has no known cause.

It also has no known cure; currently the most physicians can do is treat

prevailing symptoms, when possible, with medication. But Barry Hurwitz,

Ph.D., and Nancy Klimas, M.D. ’80, professors at the University of

Miami’s Behavioral Medicine Research Center, are investigating a

potential remedy. Working with them are researchers in the Department

of Medicine’s Allergy and Infectious Diseases Clinic.

Their study, funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, is a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial in which Procrit is prescribed to participants for four months. Used for more than a decade to treat anemia, Procrit increases the production of red blood cells, which recent research shows is low in many chronic fatigue patients.

Red blood cells deliver oxygen and blood sugars to the body, and a decreased red blood cell volume may be the cause of fatigue.

As many as 1.3 million people suffer from chronic fatigue, but up to 85 percent are not diagnosed or are not getting proper care.

“Individuals are often stigmatized—they’ve been told their illness isn’t real, it doesn’t exist, and it’s all in their head,” says Hurwitz. “People with chronic fatigue syndrome face an incredible burden just getting doctors to take their symptoms seriously.”

Following the Letter of the Privacy Law

Strictly Confidential

![]() ioethics

has long been a research strength at the University of Miami. Now that

computers, health care, and patient privacy have necessitated a new, nationwide

privacy law—better known as HIPAA, the Health Insurance Portability

and Accountability Act—UM’s expertise in privacy education is

more sought-after than ever before.

ioethics

has long been a research strength at the University of Miami. Now that

computers, health care, and patient privacy have necessitated a new, nationwide

privacy law—better known as HIPAA, the Health Insurance Portability

and Accountability Act—UM’s expertise in privacy education is

more sought-after than ever before.

“Preparation

required to comply with this law will transform U.S. health care,”

says Kenneth Goodman, Ph.D., director of UM’s Bioethics Program and

codirector of University-wide Ethics Programs.

“Preparation

required to comply with this law will transform U.S. health care,”

says Kenneth Goodman, Ph.D., director of UM’s Bioethics Program and

codirector of University-wide Ethics Programs.

The law requires hospitals, doctors’ offices, pharmacies, and other individuals and entities to develop policies and procedures for protecting personal information, together with a privacy education plan. The deadline for implementing a working privacy education program is April 2003.

“Getting up-to-speed with privacy requirements is not a nicety nor a courtesy,” says Goodman. “Morality demands it, and it’s the law. Fortunately, this is an area of expertise at the University of Miami.”

The new privacy law originally was to have been written by Congress, but when legislators failed to meet their own deadline, the task was assumed by then-Secretary of Health and Human Services Donna E. Shalala, Ph.D., now president of the University of Miami.

The University’s privacy education team includes Reid Cushman, Ph.D., of the University of California at Berkeley, a health informatics and policy expert; Anita Cava, J.D., professor of business law at the UM School of Business Administration and codirector of UM’s Ethics Programs; and Stephanie Anderson, M.D., J.D., an Ethics Programs health law fellow.

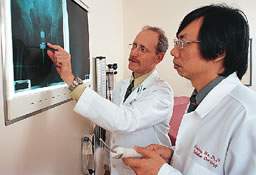

![]() new

device developed at the University of Miami Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer

Center holds promise for reducing hospital stays, improving treatment

outcomes, and cutting costs for women with cervical and other gynecologic

cancers.

new

device developed at the University of Miami Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer

Center holds promise for reducing hospital stays, improving treatment

outcomes, and cutting costs for women with cervical and other gynecologic

cancers.

|

||

|

Created by Aaron Wolfson, M.D., associate professor of radiation oncology and codirector of UM/Sylvester’s Gynecologic Cancers Site Disease Group, and Xiaodong Wu, Ph.D., chief medical physicist at the University, the device delivers low-dose-rate radiation therapy, also called LDR brachytherapy, with unmatched accuracy. UM/Sylvester is the only medical center in the nation currently testing the device.

Called the University of Miami Wolfson-Wu Universal GYN applicator in its patent application, the device is a plastic cylinder that is temporarily implanted in the vagina in a ten-minute surgical procedure. Predetermined doses of radiation flow throughout the unit, targeting cancerous tissue while sparing healthy tissue.

Current LDR brachytherapy applicators require two surgical procedures and hospital stays, each lasting two to three days. The new device requires only one stay and is withdrawn at the completion of treatment with no need for pain medications. In addition, the new device uses the same dose of radiation as the earlier method, but it destroys more cancer cells because it closely mimics how the body naturally emits radiation at a very low level.

GENE IS PREVALENT AMONG AFRICAN-AMERICANS

Demystifying Deafness

![]() esearchers

at the University of Miami Ear Institute have identified a new member

in a gene family that is thought to predispose individuals toward deafness.

This newest sibling in the connexin gene family is attached specifically

to the African-American population.

esearchers

at the University of Miami Ear Institute have identified a new member

in a gene family that is thought to predispose individuals toward deafness.

This newest sibling in the connexin gene family is attached specifically

to the African-American population.

|

||

Reported in Human Molecular Genetics, the findings may help researchers figure out on a molecular level what goes wrong in deafness and eventually design a therapy. During the next two to three years, however, hearing screenings will likely look for this gene mutation, especially in African-Americans, as a possible cause for non-syndromic deafness. In this condition, no other patient problems or symptoms known to cause deafness are present.

“Mutations in four members of the connexin gene family were already known to be the underlying cause of deafness,” says Xue Z. Liu, M.D., Ph.D., lead investigator and assistant professor of otolaryngology.

Since this gene family’s involvement in deafness suggested that other individual genes within the connexin group (Cx) should be considered as candidates for non-syndromic deafness, the researchers looked for mutations in the connexin 43 gene (Cx43). They used DNA samples from 126 people—26 deaf African-Americans and 100 normal-hearing individuals—and analyzed genetic changes in Cx43. Tracing these patient connections and comparing changes between deaf and normal-hearing people, Liu’s team identified a role for the Cx43 gene in non-syndromic deafness. Four of the 26 deaf individuals had the Cx43 mutation, known as GJA1.

“GJ stands for gap junction proteins,” Liu explains. “These gap junctions connect adjacent cells and facilitate the processing of one’s hearing. When the mutations are present at this particular gap junction, there is an interruption in the auditory process.”

![]() he

School of Medicine reaches a milestone this year: its 50th anniversary.

The celebration, however, has already begun with a reception last February

in Tallahassee, to thank the Florida legislature for introducing academic

medicine to the state in 1951. John G. Clarkson, M.D. ’68, senior

vice president for medical affairs and dean, and UM President Donna E.

Shalala, Ph.D., discussed the school’s first 50 years and its plans

for the future.

he

School of Medicine reaches a milestone this year: its 50th anniversary.

The celebration, however, has already begun with a reception last February

in Tallahassee, to thank the Florida legislature for introducing academic

medicine to the state in 1951. John G. Clarkson, M.D. ’68, senior

vice president for medical affairs and dean, and UM President Donna E.

Shalala, Ph.D., discussed the school’s first 50 years and its plans

for the future.

Class began on September 22, 1952, for the first Florida-trained physicians. In commemoration of that day, 2002’s first-year medical students will be guests at a luncheon on September 20. A 50th birthday party to thank staff and faculty is planned for November 20 at the Schoninger Research Quadrangle.

Alumni Weekend, January 31–February 1, 2003, will feature a 50th Anniversary Symposium on the medical school’s beginnings and growth. Speakers will include members of the first class, former deans, and former University presidents. A special session on the school’s future will be led by Dean Clarkson and President Shalala. A time capsule also will be placed in the quadrangle to commemorate the school’s half-century of accomplishments.

Details on these events and others, historical photos, and school facts and figures will soon be available online by accessing the 50th Anniversary link on the School of Medicine’s Web site, www.med.miami.edu. Further information is available from the Office of Public Affairs and Community Relations at 305-243-3453.

Helping Our Heroes Stay Active

Life and Limb

![]() here

are an estimated seven to ten million land mines in Afghanistan. As a

result, many lower limb amputations are expected during the war against

terrorism. Hence, the United States Department of Defense has appointed

a special advisor: Robert Gailey, Ph.D., P.T., assistant professor in

the Department of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation’s Division of Physical

Therapy.

here

are an estimated seven to ten million land mines in Afghanistan. As a

result, many lower limb amputations are expected during the war against

terrorism. Hence, the United States Department of Defense has appointed

a special advisor: Robert Gailey, Ph.D., P.T., assistant professor in

the Department of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation’s Division of Physical

Therapy.

|

||

|

||

“For the first time, the military is adopting a program of encouraging soldiers who lose a limb to return to active duty when they are successfully rehabilitated,” Gailey says.

A specialist in amputee rehabilitation, Gailey and a colleague established the Athletes with Disabilities chapter of the American Physical Therapy Association. He also is a member of the Disabled Sports USA medical advisory group. For the next three years, he will work with military personnel on post-amputation care and prosthetic rehabilitation, as well as consult on individual cases.

“There have been relatively few amputations during recent military actions, so coupled with advances in prosthetic rehabilitation, the military wanted to be ready to provide the most current, comprehensive care available,” says Gailey.

Gailey recently presented a three-day course to 55 rehabilitation personnel from the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C. He discussed prosthetic updates, as well as acute and rehabilitation care for traumatic amputees. With the Department of Defense program focusing on the military’s active duty athletic requirements, Gailey also taught running, jumping, load carrying, agility skills, and gait-training techniques to amputees seeking a return to active duty.

Gailey has traveled with the U.S. Disabled Sports Team as a medical trainer to the Paralympic Games in Barcelona, Seoul, and Atlanta and will do so at the Athens Games in 2004. His training put former competitive swimmer Carolina Bulow, M.S. ’98, back into her sport after amputation—and into the Paralympic Games in Barcelona. He now is working with Paralympic gold medalist Danny Andrews, a member of the University of Miami track and field team and the first disabled athlete to compete in NCAA Division I track and field. Andrews is training to compete in the 2004 Paralympic Games.

![]() spirin

could prevent chemotherapy-induced hearing loss, according to researchers

at the University of Miami Ear Institute and collaborators at the University

of Michigan.

spirin

could prevent chemotherapy-induced hearing loss, according to researchers

at the University of Miami Ear Institute and collaborators at the University

of Michigan.

Thomas

Van De Water, Ph.D., research professor of otolaryngology at the Ear Institute,

has long worked to protect hearing while preserving the efficacy of cisplatin

chemotherapy in animal models. His first research used a drug injection

that provided complete protection of hearing and kidney function but interfered

with the chemotherapy’s ability to eradicate cancer. His second phase

used the same drug, but instead injected it into the middle ear cavity.

Reported in the journal Neurotoxicology, this method protected

hearing and did not interfere with cisplatin’s ability to treat cancer

because it was delivered only to the inner ear fluid.

Thomas

Van De Water, Ph.D., research professor of otolaryngology at the Ear Institute,

has long worked to protect hearing while preserving the efficacy of cisplatin

chemotherapy in animal models. His first research used a drug injection

that provided complete protection of hearing and kidney function but interfered

with the chemotherapy’s ability to eradicate cancer. His second phase

used the same drug, but instead injected it into the middle ear cavity.

Reported in the journal Neurotoxicology, this method protected

hearing and did not interfere with cisplatin’s ability to treat cancer

because it was delivered only to the inner ear fluid.

In another project, published in Laboratory Investigation last May, Van De Water and his colleagues used the same delivery method to inject rats with aspirin—humans could take it orally—and successfully protected hearing function, partial kidney function, and retained cisplatin’s cancer-fighting ability.

“Since my University of Michigan colleagues have already run a successful human trial using aspirin to protect against antibiotic-induced hearing loss,” says Van De Water, “the chemo study should move into clinical trials within two years.”

ENZYME IS KEY TO RESTORING NERVE-MUSCLE CONNECTION

Damage Control

![]() hysicians

may one day be able to repair the nerve-muscle connection that is destroyed

by gases and pesticides or damaged in some genetic disorders, as a result

of studies under way at the University of Miami School of Medicine.

hysicians

may one day be able to repair the nerve-muscle connection that is destroyed

by gases and pesticides or damaged in some genetic disorders, as a result

of studies under way at the University of Miami School of Medicine.

|

||

|

||

Richard L. Rotundo, Ph.D., professor of cell biology and anatomy and neuroscience, has worked with the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE), which terminates muscle contractions.

“If this enzyme is completely inhibited, it’s almost instantly fatal,” says Rotundo, whose findings were published in Nature Neuroscience. “The ability to terminate neurotransmission is very important.”

Nerve gases like those released in the Tokyo subway system in 1995 cause illness and death by disabling AChE. “It doesn’t take much more than a high school chemistry education to produce these gases,” Rotundo says. “It’s pretty scary.”

The same damage can be caused by pesticides such as malathion, which structurally are similar to nerve gases. The United Nations estimates that pesticide poisoning causes 30,000 deaths a year.

For years Rotundo has studied how synapses develop between nerves and muscles. This latest research uses genetically engineered mice to establish how AChE attaches to a neuromuscular synapse.

Rotundo and his colleagues also have studied where and how AChE is made and how it knows where to go. They discovered that cell nuclei at the site of nerve-muscle contact produce AChE, while others don’t.

In research using quails, frogs, and mice, Rotundo has transplanted AChE molecules from one species to another, getting them to attach and function successfully. “We’re hoping eventually we can discover how AChE is attaching to human synapses,” Rotundo says. “By understanding the whole targeting system we can design custom molecules.”

Those molecules could be injected into a patient exposed to pesticide, preventing or stopping the damage if treated quickly enough. Decoding of nerve-muscle connections also could provide important clues to neuromuscular diseases and even to Alzheimer’s disease.

![]() young whistleblower at the FDA in the early 1960s ended thalidomide’s

use for morning sickness, but the drug is showing new promise in treating

other conditions, namely cancer.

young whistleblower at the FDA in the early 1960s ended thalidomide’s

use for morning sickness, but the drug is showing new promise in treating

other conditions, namely cancer.

Specialists at the University of Miami Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center are conducting a study to find out whether thalidomide, combined with standard chemotherapy agents paclitaxel (Taxol) and paraplatin (Carboplatin), can keep ovarian cancer patients disease-free longer than current therapy can.

“There

is no doubt that in previous generations, thalidomide was a frightening

word,” says Ramin Mirhashemi, M.D., gynecologic cancer specialist

and lead investigator of the study. “But for women outside childbearing

age, which nearly all of these patients are, and most have even gone through

hysterectomies, this new regimen holds promise.”

“There

is no doubt that in previous generations, thalidomide was a frightening

word,” says Ramin Mirhashemi, M.D., gynecologic cancer specialist

and lead investigator of the study. “But for women outside childbearing

age, which nearly all of these patients are, and most have even gone through

hysterectomies, this new regimen holds promise.”

Ovarian cancer is the deadliest gynecologic cancer in the United States. Most women are not diagnosed until they are at advanced stages.

In this study, after initial surgery to remove the bulk of cancerous tumors, stage III and IV patients are given thalidomide plus paclitaxel and paraplatin.

“Thalidomide is an immune system stimulant that has a positive impact on the cancer-fighting CD8 cell,” Mirhashemi explains. “Cancer cells release vascular growth factors that promote formation of new blood supply to the tumor to support its continued growth. Since thalidomide down-regulates vascular growth, we think it will be active against the chemotherapy-resistant cells still present after therapy.”

NEW TECHNIQUES EXPAND ISLET CELL TRANSPLANTS

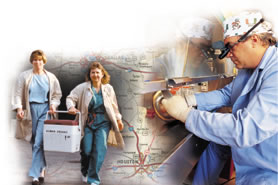

Going the Distance

![]() uccessful

transplants are impossible without successful organ donation. Researchers

at the School of Medicine’s Diabetes Research Institute (DRI) are

now revolutionizing patient care with this truth in mind. Through two

new groundbreaking discoveries, DRI scientists are expanding the base

of patients who can receive an islet cell transplant to treat Type 1 diabetes,

as well as broadening the population of organ donors that make such a

treatment possible.

uccessful

transplants are impossible without successful organ donation. Researchers

at the School of Medicine’s Diabetes Research Institute (DRI) are

now revolutionizing patient care with this truth in mind. Through two

new groundbreaking discoveries, DRI scientists are expanding the base

of patients who can receive an islet cell transplant to treat Type 1 diabetes,

as well as broadening the population of organ donors that make such a

treatment possible.

The first innovation involves the latest cellular isolation and preservation

technologies developed at the DRI. A clinical trial at Baylor College

of Medicine and Methodist Hospital in Houston, Texas, is employing techniques

created by DRI researchers that allow donor pancreases from any state

in the country to be processed in Miami—the fragile cells extracted

from them, preserved, and successfully returned for transplantation in

that state.

The first innovation involves the latest cellular isolation and preservation

technologies developed at the DRI. A clinical trial at Baylor College

of Medicine and Methodist Hospital in Houston, Texas, is employing techniques

created by DRI researchers that allow donor pancreases from any state

in the country to be processed in Miami—the fragile cells extracted

from them, preserved, and successfully returned for transplantation in

that state.

Patients with diabetes no longer need to live close to an islet isolation facility to be candidates for this procedure. Through the study, a Houston woman recently became the first successful islet cell transplant recipient in Texas. Within 24 hours of receiving insulin-producing cells from the DRI, her body began producing the life-saving hormone on its own for the first time in 30 years.

“I’m delighted that we have been the first in the U.S. to demonstrate that islets processed at one center can be safely preserved, transported, and transplanted at another institution across the country,” says Camillo Ricordi, M.D., scientific director of the DRI and the Stacy Joy Goodman Professor of Surgery and Medicine at the School of Medicine.

In a second study, scientists at the DRI have found a way to preserve previously “unusable” pancreases from older organ donors and procure their islet cells for transplant. Each year 4,500 pancreases of the 6,000 donated are discarded and not used for transplantation, including those that are earmarked as too old. But with a new method that uses oxygenated perflurocarbons (PFC) to extend the upper age limit of organ donors, DRI researchers are looking to change the statistics.

Islet cells are notoriously sensitive to oxygen deprivation, a hazard during preservation and isolation. Islet cell recovery was significantly improved when researchers added PFC, known for the ability to transport oxygen, to the traditional cold preservation solution. Using human pancreases from donors aged 51 to 64 and obtained from organ procurement organizations after they could not be allocated for whole organ transplant, DRI scientists achieved isolation of an average of 548,513 islets per pancreas from the PFC group. The control group yielded only an average of 180,740 islets per pancreas. None of the islet preparations from the control group were considered suitable for transplantation, while four patients with Type 1 diabetes have been insulin-independent for as long as six months with islets from organs preserved in the PFC-rich solution.

DRI investigators now routinely use a PFC-enriched solution for preserving all donor pancreases processed for islet cell transplantation.

Photography: John Zillioux and Custom Medical Stock Photo

Illustration: Dave Plunkert