ntil

recently South Florida had one large pediatric rehabilitation center

in Broward County and a smaller unit at UM/Jackson. Many children needing

neuro-rehabilitation had to go to adult centers along with the middle-aged

and elderly, who have very different physical and psychological needs.

There was almost no follow-up after the children were released from these

centers and experienced new complications as they returned to home and

school.

The Broward center no longer accepts children, but through the vision of two School of Medicine faculty members, a multidisciplinary team at UM/Jackson is treating larger numbers of infants, school-age children, and adolescents with brain injuries and collecting much-needed information about their recovery.

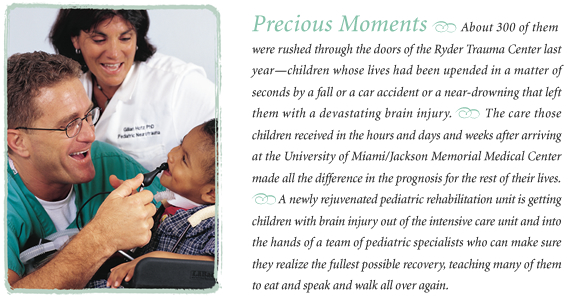

“ Even a mild brain injury has severe consequences,” says Gillian Hotz, Ph.D., assistant professor of surgery in the Division of Trauma and Surgical Critical Care, and one of the forces behind the Pediatric Rehabilitation Unit. “Because kids are not little adults, we need special centers geared to the unique therapy and care these kids require.”

![]()

When she realized about three years ago that

hundreds of children who come to UM/Jackson with neurological trauma

each year were not getting

the services they needed, Hotz went in search of a physician to join

her quest to improve inpatient rehabilitation and outpatient care for

these children. The result was a dynamic partnership with intensivist

John Kuluz, M.D., associate professor of pediatrics, who does basic science

research on how brain cells recover from injury and clinical research

in the pediatric ICU on the management of brain injury.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

When car accident victims came to the trauma center, Kuluz was seeing remarkable recovery of every organ but the brain. The need for clinical research on these children is immense, Kuluz says, because “there is no magic bullet for the brain.”

“ I used to think of the trauma center and the ICU as the most important treatment areas,” he says. “Now I know that what we do there, while extremely important, is only one component of the health care needs of these children. I now recognize that equally important interventions are needed for months, and in some cases years, after the injury. A long-term commitment must be made to these children; the primary care physician often lacks the experience to provide this care.

“Pediatric rehabilitation is a relatively new field,” Kuluz says. “We take the kids nobody else can handle. We take kids other centers say aren’t ready for rehab, who in the past would have gone to a nursing home. For example, we are the only pediatric rehab center in Florida that accepts ventilator-dependent children. We have two children now with spinal cord injuries who are on ventilators.”

It’s been a year and a half since an ambulance brought young Joshua Hernandez to the Ryder Trauma Center with a severe brain injury. On the last day of school before Christmas break in 2001, eight days after his 12th birthday, Joshua was playing ball outside the day care center where his mother works. When the ball rolled into the street, he ran after it. He was hit by a car.

“ The car didn’t even have time to stop; there was no screeching of brakes,” says Joshua’s mother, Judith Hernandez. “He hit the hood of the car and then landed on the concrete. So he had a double impact.”

In the trauma center’s intensive care unit, Joshua remained in a coma for six days. Then he was moved to a pediatric floor in Jackson, where Kuluz and Hotz intervened. Their expertise in brain injury provided answers and some relief for the family. “You could see the stress lift off the parents’ shoulders,” Hotz says.

![]() hey had Joshua transferred to the pediatric rehab

unit, where for weeks “he

still didn’t walk, he didn’t talk—you could say he

wasn’t

really there,” Judith Hernandez says. He was suffering post-traumatic

amnesia, Hotz says, making him agitated and almost robot-like.

hey had Joshua transferred to the pediatric rehab

unit, where for weeks “he

still didn’t walk, he didn’t talk—you could say he

wasn’t

really there,” Judith Hernandez says. He was suffering post-traumatic

amnesia, Hotz says, making him agitated and almost robot-like.

His mother pressed for answers. “I remember asking the doctors, Will he just one day wake up, like you see in the movies, and say, ‘I remember this, I remember that’?” his mother says. “The very next day was the day he says he came back to earth.” Or as Hotz says, “His lights came on.”

Joshua started talking, telling his mom and his twin brother a jumble of recollections that were flashing back into his consciousness, like the kind of car his mother used to drive. He realized he was suddenly remembering. That was the first step of a slow, steady journey back to his old self.

His mother gives a little of the credit for Josh’s recovery to miracles—and a lot to the therapists and physicians. “If it hadn’t been for all the therapies he had, there is no way he would have accomplished what he did in such little time,’’ she says. “All the therapists were great. They could tell me he’s going to do this, and then it would happen. I couldn’t have asked for a better team to get me through this.”

Along with treatment for the child, therapy is critically important for the family inevitably torn apart by the child’s brain injury, Kuluz says. “When a crisis like this hits, it’s like a bomb going off. Whatever little dysfunction they have gets amplified.”

Part of the shock is realizing how little recovery may be possible—and how long it will take. “When they’re really severely injured, the goals are very small,” Hotz says. Therapists work on visual tracking, head control, swallowing, sitting. “They depend on us for every aspect of their daily living,” says Eddy Paez, associate head nurse in the rehab unit.

Doctors worry that the youngest children may never develop reasoning skills and will later fall through the cracks in a school setting. “For kids under six, parents are their frontal lobes, the part of the brain responsible for executive functions,” Hotz says. “Children start making their own decisions in first grade.”

Developmental deficits may show up at various stages. “You don’t know what problems they’ll have in grade five when they need more advanced thinking,” Kuluz said. “Or think about grade six or seven when they have to use their executive functioning to handle different classes, different teachers, lockers. It’s critical that we follow them and make sure they get the services they need.”

The pressure of continuing therapy, tutoring, and eighth grade built up for Joshua Hernandez, causing something of a behavioral relapse last spring. More serious behavior problems are not uncommon among children with neurological injuries, Kuluz says, particularly adolescent boys. Joshua’s mom says she is pushing him a little less now, and he is doing better.

He still has some memory problems, but he is back to playing baseball and other sports. “Step by step, he is going to be a functional human being in life,” his mother says. “That’s all I can ask for.”

Adds Hotz, “He is a very intelligent kid, so he’ll keep getting better. He achieved an excellent outcome.”

![]() he outcome has been bleakly different for little Chucho Wongden, who

fell before his third birthday. His spinal cord was swollen from his

upper neck

to mid-chest,

and he lost all motor function from the neck down. He needs a ventilator

to breathe because a section of his spinal cord has atrophied.

he outcome has been bleakly different for little Chucho Wongden, who

fell before his third birthday. His spinal cord was swollen from his

upper neck

to mid-chest,

and he lost all motor function from the neck down. He needs a ventilator

to breathe because a section of his spinal cord has atrophied.

Hotz is concerned about where Chucho will go next. He needs 24-hour medical care, and the grandmother who is his guardian cannot provide that care by herself because it is so complex. “This is a very bright child,” Hotz says—a child with a strong attachment to Kuluz, who moonlights as his barber.

As they are committed to following Chucho, Kuluz and Hotz want to be able to provide long-term services for every child with neurological injury. They place particular emphasis on their follow-up clinic, which serves children on an outpatient basis. A high priority for the future is a day program, which would bring patients who have been sent home from the rehab center back for school, social activities, and continuing therapy.

As the program grows, the team remains dedicated to making a difference for people who have been through an enormous shock—and whose lives are changed forever.

Joshua Hernandez’s twin brother, Jonathan, “has completely matured over this past year because he has taken over the role of father for Joshua,” Judith Hernandez says. “He takes care of his brother. I’m separating them a little so Joshua doesn’t expect so much from his brother. Jonathan has his own things to take care of at this age.”

And Mom deals with the complexities of raising teenagers, exacerbated in one of them by the effects of a serious brain injury. “You just go on,” Hernandez says. “It’s like a roller coaster, day by day seeing how you’re going to handle the day.”

Never far from her consciousness is her profound gratitude that Joshua woke up from his “dream,” as he describes it, and came back down to earth. “He’s basically fine,” Hernandez says. “Nobody could even tell that he went through such a traumatic brain injury.

“ All the things that happened to him, I believe, were small miracles.”