DEVICE HELPS AVERT SURGERY-RELATED HEARING LOSS

Know the Flow

![]()

he

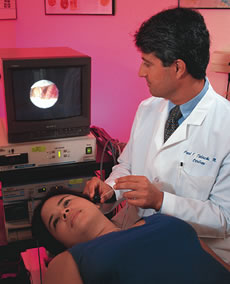

School of Medicine and College of Engineering are working to perfect

the Otic Probe, a device that measures blood flow to the inner ear during

surgery.

“We have known that blood flow can

drop during surgery, but had no way to directly monitor it,” says

Fred Telischi, M.D., director of the University of Miami Ear Institute

and principal

investigator of the

study, funded by the National Institutes of Health. “Reduced blood

flow can promote hearing loss, but if we can monitor it and administer

corrective drugs before any loss occurs, surgical outcomes will further

improve.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The prototype for the monitoring device adapted existing laser and Doppler technology to the human ear, says Telischi, associate professor of otolaryngology, neurological surgery, and biomedical engineering. Doppler technology, typically associated with weather forecasting and marine applications, measures changes in wave frequency to determine the flow of air or water. The Doppler laser used in the Otic Probe measures blood flow within the cochlea to determine its direction and strength, in order to assure that it doesn’t drop too low to sustain hearing function.

Human trials on the device began last spring. In a few years, Telischi says, the device may be used to monitor and treat blood flow right in a physician’s office.

“For patients who come in with sudden hearing loss, say within 24 to 48 hours, we may be able to identify whether or not blood flow was interrupted and treat it immediately,” adds Telischi. “The prototype also has a drug delivery system so if the loss of flow is identified, it can be resumed as soon as possible.”

Life-Saving System Acts as ‘Liver Dialysis’

![]()

iver specialists at the University of Miami School

of Medicine are successfully extending the patient’s ability not

only to await a compatible organ, but in some instances to completely

avoid a liver transplant. They are studying the merits of the ELAD system—Extracorporeal

Liver Assist Device—on patients who suffer acute liver failure.

“The

system is referred to as ‘liver

dialysis,’ a bridge to

transplant that buys patients time until a donor becomes available,” says

Guy Neff, M.D., University of Miami liver specialist and the study’s

principal investigator.

“The

system is referred to as ‘liver

dialysis,’ a bridge to

transplant that buys patients time until a donor becomes available,” says

Guy Neff, M.D., University of Miami liver specialist and the study’s

principal investigator.

“Roughly a dozen patients throughout this seven-site national study have successfully been supported until a liver became available, but at UM we have had two patients who completely averted a transplant,” Neff adds.

Manufactured by VitaGen, Inc., ELAD uses human liver cells to perform functions normally handled by a patient’s own liver. “This system appears to remove toxins from the blood, convert nutrients to energy, and process drugs, giving the liver enough time to go through its natural regeneration process,” Neff explains.

“Our first patient who enrolled in the study suffered from both liver and kidney failure,” Neff says. “Ninety percent of those patients die unless they receive a new liver.”

But after less than two days on the ELAD system, she had improved dramatically—enough so that when a donor liver became available, she was no longer considered the most critical patient, and the organ was used to save another young woman.

DEPARTMENT OF REHABILITATION MEDICINE ESTABLISHED

Function Takes Form

![]()

The

Department of Rehabilitation Medicine has been established as the first

new department at the

School of Medicine in more than 15 years. The interim chair, Marca Sipski,

M.D., sees the initiative as one that blazes a new frontier in patient

care—at the school and statewide.

“When I came to Florida to join UM just a couple

years ago, the area was lacking in terms of dedicated efforts in physical

medicine and rehabilitation,” she

says. “But I saw a lot of potential, and in many ways, we’re

breaking new ground.”

“When I came to Florida to join UM just a couple

years ago, the area was lacking in terms of dedicated efforts in physical

medicine and rehabilitation,” she

says. “But I saw a lot of potential, and in many ways, we’re

breaking new ground.”

The department will streamline clinical services for patients with rehabilitative needs, including acute consultations and inpatient treatment for neurologic or musculoskeletal dysfunction, medical illnesses, and traumatic injuries, as well as outpatient care and follow-up.

“The conceptual view in creating the department is to bring all rehabilitation services under one umbrella,” says Sipski. “Not only will we tighten up and improve the services already provided, but we will bring in new areas of treatment as well.”

Rehabilitation physicians will supervise therapies to return patients to their optimal level of functioning, in addition to providing lifelong medical care for people with disabilities. Pediatric rehabilitation and progressive care for amputees will be introduced, along with specialized services for disabled women. Academic opportunities for students and residents are planned, and additional physicians will be recruited, as necessary.

“The creation of the department offers us the opportunity to significantly expand our services to patients while reducing duplication and inefficiency,” says John G. Clarkson, M.D. ’68, senior vice president for medical affairs and dean of the School of Medicine.

Current research efforts under the direction of rehabilitation physicians, including the South Florida Model Spinal Cord Injury System, will be augmented, as will studies to improve muscle function and sexual response, and decrease osteoporosis and spasticity in patients with spinal cord injuries and multiple sclerosis. Translational research will focus on promoting recovery from traumatic injuries and studying medications and rehabilitative therapies to speed discovery from the lab to the clinic, offering the most effective treatment for each patient.

|

UM/Sylvester at Deerfield Beach Opens |

UM/Sylvester at Deerfield Beach can be reached at 954-571-0111. |

NATIONAL PARKINSON FOUNDATION GRANTS $9 MILLION TO MEDICAL SCHOOL

Committed to a Cure

![]()

he National Parkinson Foundation launched a major

expansion in research toward a cure for Parkinson’s disease with

a special grant of $9 million to the School of Medicine, marking the

largest financial

award from the foundation to a single institution.

“The University of Miami and the National Parkinson Foundation

have long shared a vision of creating a world-class Parkinson center

in Miami,

and this grant will make it possible for us to achieve that goal together,” says

John G. Clarkson, M.D. ’68, senior vice president for medical

affairs and dean.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The affiliation between the institutions began in 1979 through the efforts of Nathan Slewett, then a new board member of the NPF, and Bernard J. Fogel, A.B. ’57, M.D. ’61, then assistant vice president for medical affairs at the School of Medicine and now dean emeritus. The two leaders built a relationship that led to the establishment of the UM-NPF Parkinson Center in 1999. Over the years the foundation has granted millions of dollars to support Parkinson’s disease programs at the School of Medicine.

“This is truly a historic moment in our relationship with the University of Miami School of Medicine, which has been going strong for more than 20 years and has been one of deep satisfaction,” says Slewett, now chairman of the board of the NPF. “The grant of $9 million to UM clearly reinforces our joint efforts to remain as partners in our determination to put an end to Parkinson’s disease.”

The disease is a motor system disorder that occurs when dopamine-producing neurons or nerve cells in the brain die or become impaired. Although 15 percent of the 1.5 million Americans affected by the disease are diagnosed before age 50, it is generally considered to target older adults, with one in 100 over the age of 60 affected. Basic neuroscience research at the center will look to the cause of neuronal death, while applied neuroscience efforts aim to develop stem cells to replace dead neurons and transport nerve growth factors to dying neurons. Clinical research will investigate new drugs for treatment, while expanding studies on deep brain stimulation, a technique that uses electric currents to replace the effect of missing cells in Parkinson’s disease.

|

UM Helps Create First Online Medical School |

World-renowned leaders in medical education, program directors Ronald M. Harden and Ian Hart were drawn to the School of Medicine’s success in curriculum advancement, having worked with the school’s Center for Research in Medical Education (CRME). IVIMEDS will pool resources from participating schools for the benefit of students around the world, including technological learning tools already perfected at the CRME. Each partner school will develop its own curriculum from the online library, with pilot classes scheduled for fall 2004. “The University of Miami is involved with IVIMEDS because our leaders are open to new ideas,” says S. Barry Issenberg, M.D., director of educational research and technology at the CRME. In support of the project, School of Medicine Dean John G. Clarkson, M.D. ’68, has joined the Executive Committee of the Steering Council for IVIMEDS. UM President Donna E. Shalala, Ph.D., is a member of the IVIMEDS Development Board. |

EXPERTS IN MOVEMENT DISORDERS JOIN UM

On the Move

![]()

aking

a significant stride in its treatment of movement disorders, the School

of Medicine welcomed two of the discipline’s leaders last

fall: James M. Schumacher, M.D., and Bruno V. Gallo, B.S. ’82,

M.D.

The pair brings nationally renowned proficiency in deep brain stimulation

(DBS), which delivers electrical stimulation to parts of the brain that

control movement. Such stimulation counteracts neurological imbalance

that

produces tremor, dyskinesia, and rigidity. After years of working together

at a clinic in Sarasota, Florida, Schumacher and Gallo have developed

their teamwork into seamless expertise. Schumacher is a neurosurgeon;

Gallo is

a neurologist. Unique to their approach is interdisciplinary collaboration

to offer comprehensive treatment. An operating room has been dedicated

for their DBS procedures.

The pair brings nationally renowned proficiency in deep brain stimulation

(DBS), which delivers electrical stimulation to parts of the brain that

control movement. Such stimulation counteracts neurological imbalance

that

produces tremor, dyskinesia, and rigidity. After years of working together

at a clinic in Sarasota, Florida, Schumacher and Gallo have developed

their teamwork into seamless expertise. Schumacher is a neurosurgeon;

Gallo is

a neurologist. Unique to their approach is interdisciplinary collaboration

to offer comprehensive treatment. An operating room has been dedicated

for their DBS procedures.

Beyond surgery, the two work to improve quality of life for patients. Their clinic incorporates physical and occupational therapy, nutrition counseling, social work, and other complements to traditional treatment with medications. Partnerships with laboratories at Harvard University and in Sweden will help bring the latest innovations to the clinic.

Collaboration between departments at the School of Medicine was a major reason Schumacher and Gallo joined the University. The strength of current relationships, such as the school’s affiliation with the National Parkinson Foundation, along with successful research programs at facilities like The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis, made the move attractive.

“It has to be a team effort, and this will be the spearhead,” Schumacher says.

For Gallo—who grew up in Miami, earned his undergraduate degree from UM, underwent internship and residency training under the direction of School of Medicine faculty, and completed a fellowship in the Department of Neurology—the decision to come on board was even easier.

“Providing these services to the people of South Florida is extra-special for me,” he says. “I’m coming home.”

![]()

ne step at a time, The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis at the University

of Miami School of Medicine is changing the lives of people paralyzed

following spinal cord injury. Miami Project researchers welcomed

Volker Dietz, M.D., director of the Swiss Paraplegic Clinic, as a

visiting scientist at the School of Medicine for four months last

winter.

Dietz collaborated with Miami Project scientists

for study of the Lokomat robotic walker, an assistive walking machine

he helped develop. Supported by an exoskeleton harness, participants

experience passive walking as the robot moves their legs along

a treadmill, bending hip and knee joints to simulate the action

of

stepping forward. Repetitive training with the device is aimed

at helping participants’ muscles relearn the functions of

walking.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

“The repetitive motion of the Lokomat helped me to walk in a more normal fashion,” says Diane Hughes, a research participant. “And I continue to have positive effects measured through better standing and walking as a result of the experience.”

For Dietz’s study at The Miami Project, participants with incomplete spinal cord injuries began retraining to walk with assistance from the device. Targeting “spinal locomotor centers,” Lokomat allowed researchers to evaluate variations to the stepping pattern and how they affect motor response in the subjects’ muscles.

“These studies will help us develop the best rehabilitation intervention, so that we can maximize function today,” says Edelle Field-Fote, B.S. ’84, M.S. ’90, Ph.D., research assistant professor at The Miami Project.

Photography: Jay Good, Darryl Strauser, Pyramid Photographics,

Rob Camarena

Illustration: Stuart Briers, Whitney Sherman, Robin Jareaux, Peter

Hoey

Specialists from UM/Sylvester’s Courtelis Center for mind

and body healing are also on site to offer complementary therapies,

such

as acupuncture and psychological support to patients and their families.

Education and outreach activities, including frequent classes, seminars,

cancer screenings, and outreach to local physicians will involve the

surrounding community. Though the bulk of clinical services will continue

to be offered at UM/Sylvester on the School of Medicine campus, patients

residing in Broward and Palm Beach counties can schedule follow-up

appointments, second opinions, consultations, and screenings for clinical

trials closer to home at the new 10,000-square-foot satellite office.

For those referred to the University of Miami medical campus for specialized

care, a shuttle from the Deerfield Beach location provides transportation.

Specialists from UM/Sylvester’s Courtelis Center for mind

and body healing are also on site to offer complementary therapies,

such

as acupuncture and psychological support to patients and their families.

Education and outreach activities, including frequent classes, seminars,

cancer screenings, and outreach to local physicians will involve the

surrounding community. Though the bulk of clinical services will continue

to be offered at UM/Sylvester on the School of Medicine campus, patients

residing in Broward and Palm Beach counties can schedule follow-up

appointments, second opinions, consultations, and screenings for clinical

trials closer to home at the new 10,000-square-foot satellite office.

For those referred to the University of Miami medical campus for specialized

care, a shuttle from the Deerfield Beach location provides transportation.