atching

the surgeons operate, it’s hard to escape the eerie resemblance to

observing two grown men play a video game in a darkened room. Standing

hip to hip, they manipulate long, narrow joysticks while staring silently

up at the television screen. Every now and then, a surgeon grunts “here”

or “okay.” But, otherwise, total silence. Even the surgical

residents and nurses quietly watching add to the feel of a hushed and

darkened video arcade.

atching

the surgeons operate, it’s hard to escape the eerie resemblance to

observing two grown men play a video game in a darkened room. Standing

hip to hip, they manipulate long, narrow joysticks while staring silently

up at the television screen. Every now and then, a surgeon grunts “here”

or “okay.” But, otherwise, total silence. Even the surgical

residents and nurses quietly watching add to the feel of a hushed and

darkened video arcade.

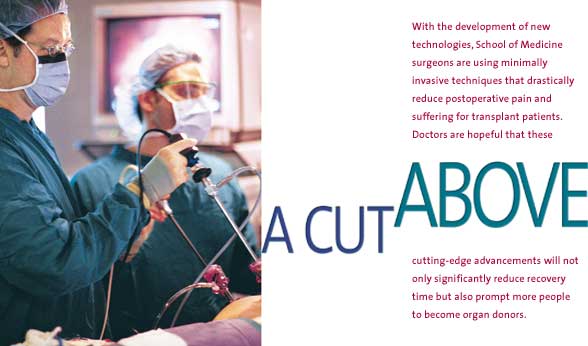

What University of Miami surgeons Robert Bailey, M.D., and Gaetano Ciancio, M.D., are doing is no game. The two are removing a kidney from a man in order to save the life of his brother, who is being prepared for the transplant in the surgical suite just steps away. In moments, transplant surgeon Joshua Miller, M.D., will run into the room, place the kidney in a small metal bowl, and race back to begin the two- to three-hour ordeal of restoring the brother’s health.

The procedure, in and of itself, is not unusual. About 50 such “live” kidney transplants are done at the medical center each year. What sets this surgery apart is the fact that the physicians are using a minimally invasive technique that will spare the donor a painful 14-inch incision around his waist, weeks of medication, and the loss of income from staying home and recovering from major surgery. Though one of the more dramatic examples of minimally invasive surgery—physicians hope the reduced discomfort and faster recovery time will encourage more people to donate kidneys—the surgery is only one of numerous such procedures School of Medicine physicians now offer.

Thanks to new technologies that allow doctors to view internal organs through a telescopic camera and long-handled surgical tools, physicians in virtually every surgical specialty at the School of Medicine now do major operations through smaller access openings in the body.

“What we’re doing now is taking an operation that usually involves an extensive incision and doing it through relatively small, half-inch to three-inch, incisions,” says Dr. Bailey, who was recruited from Philadelphia last year to direct the University’s clinical, research, and educational activities in the areas of laparoscopic and endoscopic surgery.

“That offers the patient a lot of advantages because the hospital stay is cut back; the recovery period is reduced; there’s less pain, discomfort, and use of pain medication; and there’s less scarring. If people get out of the hospital and back to work sooner, there are obviously huge financial advantages there.”

Dr. Bailey is a nationally recognized laparoscopic surgeon credited with a number of laparoscopic firsts, including the first such kidney removal in Pennsylvania. There, he created and directed the Center of Excellence in Laparoscopic Surgery at the Allegheny University of the Health Sciences.

![]() ith

more than 3,000 laparoscopic surgeries and numerous papers and texts to

his credit, he was invited in 1999 to create and direct the University’s

Center of Excellence for Laparoscopic and Minimally Invasive Surgery.

ith

more than 3,000 laparoscopic surgeries and numerous papers and texts to

his credit, he was invited in 1999 to create and direct the University’s

Center of Excellence for Laparoscopic and Minimally Invasive Surgery.

As director, he is working alongside surgeons in the operating room to teach them laparoscopic techniques and is overseeing the University’s laparoscopic training laboratory, where postgraduate and community physicians learn to perform minimally invasive procedures through computerized and hands-on simulations. He also is encouraging collaboration among the University’s established laparoscopic and endoscopic surgeons and training staff to use the specialized equipment in the minimally invasive surgical suites recently opened at UM/Jackson’s Diagnostic Treatment Center.

And

he’s adding a whole new dimension to the University’s kidney

transplant program. In the 12 months after Dr. Bailey’s arrival,

he and Dr. Ciancio, an associate professor of surgery and urology who

has been transplanting kidneys for seven years, performed minimally invasive

nephrectomies on 15 donors. In so doing, they made it much easier for

mothers, fathers, brothers, and sisters to make the sacrifice that helped

another family member live.

And

he’s adding a whole new dimension to the University’s kidney

transplant program. In the 12 months after Dr. Bailey’s arrival,

he and Dr. Ciancio, an associate professor of surgery and urology who

has been transplanting kidneys for seven years, performed minimally invasive

nephrectomies on 15 donors. In so doing, they made it much easier for

mothers, fathers, brothers, and sisters to make the sacrifice that helped

another family member live.

“People

have been reluctant to donate organs because they were concerned about

the pain and how long it would take before they could return to work,”

says Dr. Ciancio, who is national chairman of the Minority Organ Transplant

and Tissue Education Program. “Once people are aware that we’ve

removed many of the negatives, they may be more willing to step forward.”

Because of the lack of available donors, 2,295 people died last year while waiting for a kidney transplant, according to the United Network for Organ Sharing. And while most of the people who undergo kidney transplants receive their organs from individuals who have passed away, those obtaining a kidney from a close relative face better odds of retaining the organ.

Of special concern to transplant surgeons is the fact that while minorities represent about 50 percent of patients seeking kidney transplants, the lack of well-matched donors mean only about 7 percent of kidneys in 1998 went to this group. Dr. Ciancio and his colleagues hope this procedure will encourage more minorities to donate organs.

Betsy Kline, who 15 years ago donated a kidney to her sister, Nancy Varner, admits she’d be willing to do again—especially now that the procedure only involves three bullet hole-sized incisions and a four-inch incision through which the kidney is removed. When the Pompano woman awoke from surgery in the mid-1980s, she found a 13-inch scar around her waist and remembers thinking: “Is it supposed to hurt this much?”

When her sister’s kidney again failed, younger brother John Varner underwent minimally invasive surgery to donate his. “It was like night and day,” Kline says. He reported almost no pain at the incisions and only slight achiness from having air pumped into his abdomen so his kidney could be more readily viewed during surgery. “It really hasn’t been that bad,” Varner said a week after undergoing the procedure. “My biggest problem has been trying not to overdo it because I feel so good.”

While laparoscopic and endoscopic surgery have been available at the School of Medicine since the early 1990s, Dr. Bailey’s arrival signals the medical center’s commitment to expanding research, education, and clinical collaboration in these areas.

Raleigh Thompson, M.D., is confident that the new center will promote cooperation among the School of Medicine’s laparoscopic surgeons. The associate professor and chief of the Division of Pediatric Surgery learned basic laparoscopic techniques performing tubal ligations in the military and has transferred that early experience into one of the busiest pediatric laparoscopic practices in the country. He and his colleagues use the technique as their standard surgical approach to a variety of gastrointestinal repair procedures.

aving

a cooperative relationship without competition among different specialists

is one of the advantages of being at a university. It gives you the freedom

to work together,” Dr. Thompson says. “Sometimes an instrument

or technique that develops in one field may be applicable to others. Moreover,

you don’t learn laparoscopy in one day or one week. It requires training

on simulators and in the OR. Surgeons like Dr. Bailey, Dr. Leveillee,

and I can help others do their initial operations without compromising

patient care.”

aving

a cooperative relationship without competition among different specialists

is one of the advantages of being at a university. It gives you the freedom

to work together,” Dr. Thompson says. “Sometimes an instrument

or technique that develops in one field may be applicable to others. Moreover,

you don’t learn laparoscopy in one day or one week. It requires training

on simulators and in the OR. Surgeons like Dr. Bailey, Dr. Leveillee,

and I can help others do their initial operations without compromising

patient care.”

Raymond J. Leveillee, M.D., assistant professor of urology and director of endourology, laparoscopy, and minimally invasive surgery, does virtually all of his surgeries through a tiny incision. Among these are radical nephrectomies and reconstructive kidney surgeries, laparoscopic techniques he has been teaching to the University’s pediatric and adult urologists.

Though technologically advanced, laparoscopic procedures still require great skill on the part of the surgeon. Many surgeons liken it to manipulating spaghetti with chopsticks. Even so, Michael Hellinger, M.D., is convinced that laparoscopy is well worth the extra effort and cost.

“People have looked at cost and found it very difficult to assess. The surgery is more expensive because you’re using more sophisticated instrumentation, more throw-away equipment, and more staplers. The operation takes longer so the cost of the nurses, surgeons, anesthesiology, and others in the OR goes up,” says Dr. Hellinger, an assistant professor and chief of the Division of Colon and Rectal Surgery who performs laparoscopic colon resections for patients with colon cancer and a number of other diseases. “But it is offset by a shorter hospital stay,” he says. “Even more difficult to compute is the intangible cost to society and individuals of reducing a patient’s pain and recovery time, and returning to work in two weeks instead of two months.”

|

The Surgical Suite of the Future Today, surgery through tiny incisions! Tomorrow, surgery without doctors? That’s not quite the scenario envisioned for the future. But it’s not that far afield either—especially in the field of laparoscopic surgery, where the limitations of working within a very contained space benefit from the precise movements robots afford.

“It’s basically a robotic arm that holds the laparoscope more steadily than a human being could,” says Dr. Robert Bailey, director of the University’s Center of Excellence for Laparoscopic and Minimally Invasive Surgery. “Via about 20 voice commands, the surgeon can direct the scope in any direction he or she wants just by saying ‘move left, move right,’ and so on.” One of the biggest challenges surgeons now face, Dr. Bailey says, is taking advantage of the technology becoming available to the surgical suite. “In the near future, we’ll be bringing more voice recognition technology into the OR so the surgeon can control his or her environment more efficiently by adjusting equipment,” Dr. Bailey says. “We’re not far from the point where you’ll be able to increase the flow of carbon dioxide, adjust the table for positioning, turn lights on and off, and conceivably call up critical information from a patient’s chart through voice commands.” |

With

the opening of two new laparoscopic surgical suites at Jackson Memorial

Medical Center, a robotic arm will help surgeons by holding the

videoscope used to view the patient’s internal organs.

With

the opening of two new laparoscopic surgical suites at Jackson Memorial

Medical Center, a robotic arm will help surgeons by holding the

videoscope used to view the patient’s internal organs.