|

|

hree years ago readers of The New York Times, USA Today,

and other dailies opened their papers to find a chilling advertisement:

a picture of a girl wearing a black ski mask reading a ransom note. “We

may be hostages,” it read, “but today we’re the ones making

the demands. We’re truth. A generation tired of being lied to about

tobacco. Tired of replacing the 1,000 customers tobacco kills every day.”

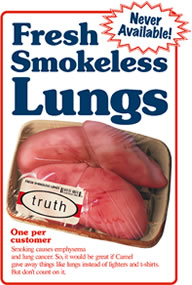

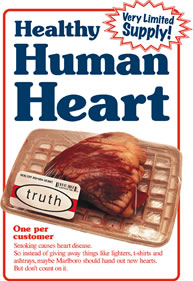

The ad, along with a series of others appearing in print, on billboards,

and on TV, was part of a “counter-marketing” campaign designed

to warn teenagers about the dangers of smoking. ![]() In

counter-marketing, a widely promoted image or perception is challenged,

causing the target group to reevaluate and, ultimately, modify its behavior.

“If you simply tell kids not to smoke, you can bet they’re going

to go out and smoke,” says Edward Trapido, Sc.D., a special consultant

to the Florida Tobacco Pilot Program (FTPP) and the director and principal

investigator of the Tobacco Research and Evaluation Coordinating Center

at the University of Miami School of Medicine. “But if you tell them

they are being manipulated, forced into doing something—like smoking

cigarettes—they’ll react to that by turning away from smoking.”

In

counter-marketing, a widely promoted image or perception is challenged,

causing the target group to reevaluate and, ultimately, modify its behavior.

“If you simply tell kids not to smoke, you can bet they’re going

to go out and smoke,” says Edward Trapido, Sc.D., a special consultant

to the Florida Tobacco Pilot Program (FTPP) and the director and principal

investigator of the Tobacco Research and Evaluation Coordinating Center

at the University of Miami School of Medicine. “But if you tell them

they are being manipulated, forced into doing something—like smoking

cigarettes—they’ll react to that by turning away from smoking.”

And turning away they are. Within two years of the launch of Florida’s highly celebrated anti-tobacco campaign, teenage smoking plummeted across the state. Cigarette use among Florida high school students dropped 18 percent; among middle school students it dropped a whopping 40 percent. So successful has been Florida’s multipronged program to reduce teen smoking that other states, as well as a federal office charged with reducing teen smoking, have patterned their programs after it. And Dr. Trapido, who also heads up the school’s Division of Cancer Control, has been key to that success. Since the inception of the FTPP in 1998, he has been charged with evaluating the effectiveness of the ad campaigns, community outreach, and other anti-smoking initiatives aimed at Florida’s youth.

|

|||||

|

|||||

Using an array of research techniques, Dr. Trapido and his staff help determine which messages stick and which ones flop. His data is used by ad agencies eager to reshape marketing campaigns, by state health officials to identify risk factors for cigarette use, and by lawmakers and other public officials to justify funds and other resources for anti-smoking efforts. “We try to ask the question, What works and what doesn’t?” Dr. Trapido says. “The more we know, the more efficient we can be about delivering our message.”

FTPP arose out of the state’s historic $13 billion settlement with the tobacco industry, reached in 1997. Florida, like many other states, sued the large tobacco companies, claiming they failed to disclose information to the public showing that cigarette smoking posed severe health risks. The suit further alleged that cigarette makers often subliminally, if not overtly, targeted youths. Studies show that more than 80 percent of all smokers began tobacco use before turning 18. Over the past decade that figure has risen. Health officials estimate that close to 300,000 Floridians now under the age of 18 will one day die from tobacco-related disease. In Florida, health care expenditures directly related to tobacco use are estimated at $4.6 billion per year, $1.7 billion of which is paid for with state and federal tax money.

Given such costs, lawmakers were eager to earmark much of the tobacco settlement money for programs to steer Florida’s youth away from cigarettes. In its first year, the FTPP received $70 million in funding. The bulk of that was used to saturate the state with ads touting the evils of smoking. Dr. Trapido says the campaign has been successful largely because of input from Florida’s youth. Student groups from around the state coined the slogan “A Generation United Against Tobacco.” They also conceived of the provocative, in-your-face style of advertising termed the “Truth” campaign—short for the tag line, “Their brand is lies, our brand is truth.”

In one TV ad the Grim Reaper asks a gathering of tobacco executives to help ease his workload. A billboard ad pictures a hairy, overweight man lounging by a pool, dressed in a skimpy bikini. “No wonder tobacco executives have to hide behind sexy models,” reads the caption. “Allowing kids to participate, to help design the campaign, made a big difference,” says Dr. Trapido. “In many ways they were able to articulate a message that adults could not.”

Dr. Trapido’s research also helped weed out ineffective ads. One ad, for example, likened cigarettes to a Venus fly trap and a young smoker to the fly. “Young people didn’t get it,” says Dr. Trapido. The ad was pulled.

![]() ut the high-profile ad campaign is just part of a larger offensive against

youth smoking. The FTPP is organized around four components: marketing

and communications, youth and community partnering, education and training,

and enforcement of anti-tobacco laws. Dr. Trapido’s role, evaluation

and research, is often considered a fifth component.

ut the high-profile ad campaign is just part of a larger offensive against

youth smoking. The FTPP is organized around four components: marketing

and communications, youth and community partnering, education and training,

and enforcement of anti-tobacco laws. Dr. Trapido’s role, evaluation

and research, is often considered a fifth component.

Other FTPP initiatives, many of which also are student-driven, are as innovative as the ad campaign. For example, the “Artful Truth” community education program teaches fourth– through sixth–graders how art, design, and advertising can be used as propaganda tools, influencing behavior despite often harmful consequences. In another example, student anti-tobacco groups around the state are lobbying county lawmakers to require convenience stores to display cigarettes behind counters, where they are less likely to be shoplifted. (Tobacco companies often replace stolen cigarettes at no cost.) Fourteen counties already have passed such an ordinance. Another program, the county-operated Tobacco Courts, has been shown by Dr. Trapido’s research to be effective at discouraging smoking by offering alternative sentencing options to youths charged with the purchase or possession of tobacco products.

Through the FTPP’s first two-and-a-half years, the University of Miami’s Tobacco Research and Evaluation Coordinating Center was responsible for evaluating the state’s anti-smoking initiatives. In June 2001 its focus shifted solely to education and training. The center also bases two full-time staff people on site in Tallahassee, providing research and evaluation support services to the Florida Department of Health, which runs the FTPP. Additionally, the center is conducting a statewide study that tracks shifts in tobacco-related attitudes and behaviors of young people. The study, the first in the nation to include children as young as fourth graders, has already revealed some important findings. For example, students who perform poorly in school or who report ambivalence toward it are more likely to use tobacco products. The study also found that despite overall declines in smoking among Florida’s youth population, non-Hispanic whites report a far greater rate of tobacco use than other ethnic groups—more than double the rate of African-American high school students. Word of the center’s success is getting around: The Minnesota Department of Health recently contracted Dr. Trapido’s team to evaluate its own anti-smoking campaign geared toward adolescents.

Despite Florida’s success at reducing youth smoking, the future of the FTPP remains somewhat in doubt. Funding was reduced from $70 million in 1998 to $39 million in 1999. That figure was later increased, but each year legislators spar over FTPP funding. Some believe all tobacco settlement proceeds should be used for anti-smoking efforts and to improve health care services for children and the elderly. Others propose tapping the funds to help balance the state budget and for other general needs. But Dr. Trapido is confident the program will continue. “We’ve been able to reduce smoking among children in Florida far in excess of what we had ever imagined,” he says. “The results speak for themselves.”