|

|

n

the Yunnan Province of south-central China, a dragon is awake. Desperate

to hold fast to a rich culture and history, but eager to claim its place

in the global community that has merged East with West, the vast population

struggles to find the balance between tradition and today. A global economy

has forever changed the opportunities available to Chinese professionals.

Women enjoy unprecedented equality. But when their country lifted its

restrictions and opened its doors to the world two decades ago, the bad

came with the good. Social advances were introduced—but so were social

ills. Chief among them, heroin abuse has reached epidemic proportions

in China’s cities and its countryside, particularly in Yunnan.

n

the Yunnan Province of south-central China, a dragon is awake. Desperate

to hold fast to a rich culture and history, but eager to claim its place

in the global community that has merged East with West, the vast population

struggles to find the balance between tradition and today. A global economy

has forever changed the opportunities available to Chinese professionals.

Women enjoy unprecedented equality. But when their country lifted its

restrictions and opened its doors to the world two decades ago, the bad

came with the good. Social advances were introduced—but so were social

ills. Chief among them, heroin abuse has reached epidemic proportions

in China’s cities and its countryside, particularly in Yunnan. ![]() Within this merger of old and young, rural and urban, yin and yang, an

American researcher is making a difference. Applying knowledge gleaned

at the University of Miami Comprehensive Drug Research Center, Clyde McCoy,

Ph.D., and an international team of experts are conducting studies that

will set a standard for preventing and treating drug abuse in China, as

well as improve those initiatives back home in South Florida and the United

States.

Within this merger of old and young, rural and urban, yin and yang, an

American researcher is making a difference. Applying knowledge gleaned

at the University of Miami Comprehensive Drug Research Center, Clyde McCoy,

Ph.D., and an international team of experts are conducting studies that

will set a standard for preventing and treating drug abuse in China, as

well as improve those initiatives back home in South Florida and the United

States.

he

dragon’s fiery breath first swept over China in smoky opium dens,

a practice of drug use that reaches back hundreds of years. Once touted

for medicinal purposes in relieving body aches or as recreation for the

elite, opium use was widespread and addiction inevitable. But in 1949,

when Communist rule cracked down on social deviance, drug use in China

vanished like a puff of smoke.

he

dragon’s fiery breath first swept over China in smoky opium dens,

a practice of drug use that reaches back hundreds of years. Once touted

for medicinal purposes in relieving body aches or as recreation for the

elite, opium use was widespread and addiction inevitable. But in 1949,

when Communist rule cracked down on social deviance, drug use in China

vanished like a puff of smoke.

China’s drug-free reputation faltered in the 1980s with sweeping reforms and greater influence from beyond its borders—a move dubbed “awakening the dragon.” Along with other illegal goods smuggled through poorly guarded borders, drugs quickly found their way into Chinese society again. Attempting to preserve their country’s pristine social status, China’s leaders kept silent about the problem.

|

||

“In Asia, nobody wants to report bad news. So the best way to do it at the beginning is just to try and cover it up,” says Shenghan Lai, Ph.D., adjunct associate professor of epidemiology at the School of Medicine and a key member of McCoy’s research team.

A graduate of the prestigious Peking University and native of China, Lai first introduced McCoy to the problem on an initial visit. “There is a very strong social stigma,” Lai explains. “A drug user in China shames his whole family, as well as his country.”

Uninformed of the heroin addiction problem in their country, Chinese citizens were not educated about the dangers and consequences of drug abuse. Twenty years later, the situation has become critical. Last summer, the United Nations outlined the severity of China’s plight, calling one consequence of drug use—HIV infection—an epidemic of “titanic proportions.” HIV cases have exploded in China, with more than two-thirds of them among people who inject drugs, primarily heroin. The solution, McCoy says, is to address the problem at its source. And in tracking the pathology of HIV infection in China, American researchers are discovering a new resource to help them understand drug use patterns in the United States.

“In

the U.S., these practices were very mature when HIV started,” McCoy

explains. “Through our research in China, we’re getting a fresh

look at the emergence of drug use, how drug use then progresses to injecting

practices, and how injecting practices progress to these severe health

consequences of HIV/AIDS, hepatitis, and other diseases. It’s a pattern,

and to understand the total risk, you have to look back to the drug use.

If you’re going to prevent HIV, you have to go back and prevent drug

use.”

“In

the U.S., these practices were very mature when HIV started,” McCoy

explains. “Through our research in China, we’re getting a fresh

look at the emergence of drug use, how drug use then progresses to injecting

practices, and how injecting practices progress to these severe health

consequences of HIV/AIDS, hepatitis, and other diseases. It’s a pattern,

and to understand the total risk, you have to look back to the drug use.

If you’re going to prevent HIV, you have to go back and prevent drug

use.”

|

||

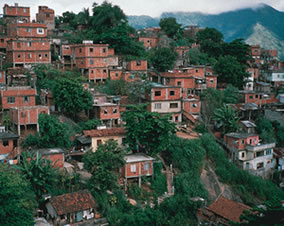

Like opium before it, heroin found its way into Yunnan by way of a desolate highway stretching from the famed Golden Triangle—Myanmar (Burma), Laos, and Thailand. Goods including fine wood, priceless gems, and highly concentrated, powdered heroin still pour in via the roadway, built in the 1940s as a passage for Allied troops during World War II. Because of the highway’s remote location, security is poor and smuggling is rampant. Like the road that connects the Golden Triangle to Yunnan’s vulnerable population, heroin has cut a path through Chinese society along which HIV infection can travel at breakneck speed, crossing borders and forever altering the health of its people.

Researchers at Yunnan University routinely studied the consequences of injection drug use, like HIV and other bloodborne diseases. They joined University of Miami investigators for an international conference in 1995 that introduced the center’s perspective on epidemic research through population studies. As chairman of the School of Medicine’s Department of Epidemiology and Public Health and director of the Comprehensive Drug Research Center, McCoy set out to offer his expertise to the troubled situation in China.

“Most participants at the conference were basic scientists,” Lai remembers. “They had never looked at the big picture. They had never linked drug abuse and HIV. That’s how Dr. McCoy made his contribution. He looked at the big picture.”

cCoy’s

contributions didn’t stop with the conference. After receiving funding

from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to continue the collaboration,

he and Lai joined Yunnan University’s President Xue-ren Wang, Ph.D.,

in establishing the Comprehensive Drug Research Center East. Encouraged

by the success of UM’s center and eager to bring its influence to

his own domain, Wang accepted the position as its director.

cCoy’s

contributions didn’t stop with the conference. After receiving funding

from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to continue the collaboration,

he and Lai joined Yunnan University’s President Xue-ren Wang, Ph.D.,

in establishing the Comprehensive Drug Research Center East. Encouraged

by the success of UM’s center and eager to bring its influence to

his own domain, Wang accepted the position as its director.

With the center in place and epidemiological investigations under way in China, McCoy focused on developing standard research principles that would maximize cooperative study between the United States and China. The task is a familiar one. As director of the School of Medicine’s Executive Office of Research Leadership, McCoy regulates guidelines and directs investigators to enforce cohesive research practices in all of UM’s laboratories.

“There has got to be equity between the researchers there and here,” McCoy says. “We are setting the standard by building infrastructure for doing research on drug abuse in China that is modeled after the study standards employed back home at our UM center.”

After years without awareness among Chinese citizens and scholars alike, questions are finally being answered through the work McCoy has introduced. Population-based studies are revealing why the heroin epidemic has been so far-reaching and how to curb consequences of unclean injection practices, such as HIV infection.

At a concentration of up to 80 percent purity, the heroin smuggled into Yunnan is highly addictive. By comparison, the drug’s purity in the United States is 6 to 25 percent. In studying the practices that led to injection of the drug, McCoy and his team found one of many stark differences between the two countries’ cultural adaptations to heroin use. Though families in China often keep syringes in the home for the administration of over-the-counter medications, illicit drug injection did not affect the population until the 1980s—when Western influence intervened and drug trafficking increased. Until then, users employed the technique of “chasing the dragon”—heating heroin to inhale its flames. But users soon sought a more effective approach.

“Because of the inefficiency of the inhaled method, once addicted, users will look for more efficient practices,” says McCoy. “And with syringes readily available in the home, the cultural adaptation to injection was much easier there than here. We were shocked at the short time period involved.”

hen

the UM and Yunnan researchers moved from the streets of China, where they

gathered demographic and epidemiological findings, to the country’s

drug rehabilitation clinics, they discovered other cultural differences.

hen

the UM and Yunnan researchers moved from the streets of China, where they

gathered demographic and epidemiological findings, to the country’s

drug rehabilitation clinics, they discovered other cultural differences.

One important addiction treatment unique to Eastern practices is the administration of a combination of native herbs. The therapy could hold an advantage over U.S. rehabilitation, which replaces one dangerously addictive substance, heroin, with another, methadone. A comparative study of the two treatments has been proposed by the U.S./China research team.

“The Chinese have 5,000 years of culture that is very different from our own, and if we don’t see them as being ‘Westernized,’ we think that difference is not as good,” McCoy says. “We need to realize that they’ve survived with this knowledge for 5,000 years, so maybe they know some good things that we need to adapt to. Researchers should ask, ‘What is best from both cultures that will improve the prevention and treatment of drug use?’

“In China, it’s not ‘Western medicine’ and it’s not ‘traditional Eastern medicine,’ ” McCoy adds. “It’s what works.”

What works so far, if the success of the collaboration between the Comprehensive Drug Research Center’s East and West sites is any indication, is continued study and partnership. At the invitation of People to People Ambassador Programs, McCoy and Lai will head back this winter and rejoin colleagues at Yunnan University to continue building the infrastructure for international research. The team also will focus on gender relationships to drug abuse, namely its prevalence among men compared to women.

Questions do remain, as do China’s epidemic of heroin abuse and its dire consequences including HIV/AIDS cases. But, as researchers at the University of Miami and in China have discovered, answers are best found and best employed by building bridges that span the globe.