|

|

![]()

inally in 1999, the National Academy of Sciences’ Institute

of Medicine released its bombshell report “To Err is Human.” Among

the extraordinary findings: 44,000 to 98,000 deaths occur each year

as a result of medical errors, which is more than the number of Americans

who die of breast cancer, AIDS, or car accidents. The report concluded

that “health care is a decade or more behind other high-risk

industries in its attention to ensuring basic safety.”

“Most of the data in the report was 10 to 20 years old—these kinds of medical errors had been going on for decades—but it was the presentation of the data that finally brought the federal government and private industry together to start dealing with this problem in a coherent fashion,” says patient safety expert Paul Barach, M.D., M.P.H. “It’s important to appreciate that sequence, because it was not just one bellwether event. It was an accumulation of events and an awareness that we cannot continue to do business as usual.”

Barach was recruited by David Lubarsky, M.D., M.B.A., chair of the Department of Anesthesiology, to run a new center with grand ambitions. The University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Hospital Center for Patient Safety aims to be a national leader in patient safety research, the place where medical centers across the country come for guidance in building safety systems.

The safety center will reflect the values advanced

by UM President Donna E. Shalala when she co-chaired the Quality Interagency

Coordination Task Force as secretary of the U.S. Department of Health

and Human Services. “For a pro-fession that promises first to ‘do

no harm,’ with this new center we will make the safety of our patients

our first priority by reducing hazards in patient care, design-ing new

curricula, and implementing safety strategies,” says President

Shalala.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

UM/Jackson trains close to 1,000 residents every year, along with hundreds of medical and other graduate students. Safety education will be integrated throughout the curriculum. “Patient safety must be at the forefront of everything we do,” says John G. Clarkson, M.D. ’68, senior vice president for medical affairs and dean of the School of Medicine. “This mindset must start on the first day of medical school.”

It was a mistake Barach made in his third year of medical school resulting in a patient’s death that led him to become one of the nation’s leading advocates for patient safety.

“I was crushed by my experience and felt guilty for many years, but it galvanized me to understand and work to change the conditions that led to the errors,” Barach says. “This is a problem that does not get enough visibility, and that’s where the patient safety center needs to begin its work.

“First, we must start by raising awareness of the problem so that more people appreciate the need to collect information on what’s working and what’s not,” says Barach. “Then we need to design a system to measure our outcomes, find out how we’re really doing. Once we’ve identified a problem, we need to work with the clinical departments to come up with a solution and then continually go back and see if the solution has solved the problem.

“I’ve described it as splicing safety into the genome of health care, like a genetic modification.”

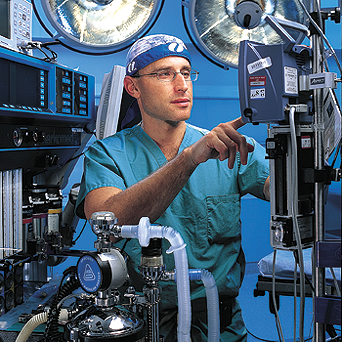

![]() t’s

no accident that Barach is a board-certified anesthesiologist and that

the patient safety center emanated from the Department of Anesthesiology.

While much of the medical world has been criticized for not making patient

safety a priority and not fixing underlying systems failures, the Institute

of Medicine identified the field of anesthesiology as the only exception.

Plagued a decade or two ago by a mortality rate of one in 10,000 to 20,000,

the current rate is about one in 400,000.

t’s

no accident that Barach is a board-certified anesthesiologist and that

the patient safety center emanated from the Department of Anesthesiology.

While much of the medical world has been criticized for not making patient

safety a priority and not fixing underlying systems failures, the Institute

of Medicine identified the field of anesthesiology as the only exception.

Plagued a decade or two ago by a mortality rate of one in 10,000 to 20,000,

the current rate is about one in 400,000.

“Anesthesia is intense. You have a physician intimately involved moment to moment in the care of a patient, and we see the impact of everything we do immediately,” says Lubarsky. “When we make a mistake and it doesn’t go well, people die. It’s devastating to a doctor to hurt somebody and to be literally right on top of it when it happens. I think that’s why anesthesia has been at the forefront of the safety movement.”

The movement began in 1982 when a patient safety committee was created as part of the American Society of Anesthesia. Anesthesiology borrowedheavily from human factors research, which examines the environment in which people operate and the circumstances that may influence their ability to function effectively. Human factors specialists, mostly engineers, design equipment for complex environments that reduces the potential for mistakes. For example, the major U.S. anesthesia machine suppliers have designed their equipment to prevent the simultaneous administration of two or more anesthesia agents.

“The goal is to create systems that make it harder and harder to make an error in the first place,” Lubarsky says. “It is very rare that one person can create a mishap; it requires miscommunication and failed rescue attempts all along the way for patient harm to occur. All sorts of bad events need to line up. So when a small error occurs, and it starts to roll downhill and gather steam, you head it off before it causes an avalanche. That’s the whole theory of patient safety.”

![]() he

new patient safety center will study how to make those systems

work. Lubarsky

describes

one system already in place at UM/Jackson before any

surgery involving a limb or organ that comes in pairs. The correct

side of the body is labeled with indelible marker and then “everyone

in the room stops what they’re doing, pays total attention,

and we all agree that this is what we’re doing. We do a time-out,” says

Lubarsky. “People have to know it is their job to make sure this

happens before every surgery and to build it into the work flow process.

That is what building a culture of safety is all about.”

he

new patient safety center will study how to make those systems

work. Lubarsky

describes

one system already in place at UM/Jackson before any

surgery involving a limb or organ that comes in pairs. The correct

side of the body is labeled with indelible marker and then “everyone

in the room stops what they’re doing, pays total attention,

and we all agree that this is what we’re doing. We do a time-out,” says

Lubarsky. “People have to know it is their job to make sure this

happens before every surgery and to build it into the work flow process.

That is what building a culture of safety is all about.”

The practice of medicine often has been compared to aviation because both fields are highly automated, complicated, and risky. But unlike medicine, aviation has discovered a way to build a successful culture of safety: During calendar year 2002, there wasn’t a single fatality in commercial aviation. To try to learn from aviation’s dramatic turnaround, the UM/JMH Center for Patient Safety has brought onboard William Rutherford, M.D., a retired United Airlines pilot who combined his medical knowledge with his love of flying.

“When you look at aviation and medicine, the two are very much the same,” Rutherford says. “Both have a very similar hierarchy where the doctor and pilot know all, and no one would ever dare challenge them.

“Mdical students very early on are subliminally suffused with the notion that if I know enough, am smart enough, and work hard enough, I will not make mistakes,” he adds. “If you look back to the 1960s, the culture of the airlines at that time was that the plane belonged to the captain, and other crew members adapted their normal flying standards to the way the captain wanted them done.”

That culture proved to be deadly, with a single event changing forever the way the airlines approached safety. Ten people died when a jetliner crashed after running out of gas near Portland, Oregon, in December 1978. The investigation found that two other crew members in the cockpit knew they were low on fuel, but they said nothing and let the captain make the mistake. What followed at United Airlines was a dramatic restructuring of training that ultimately became an industry standard.

Rutherford says the message of the training was “subordinate crew members need to stand on your own two feet, make your concerns known, and pay attention in the cockpit because you’re also responsible for the safe outcome of the flight. And it’s your job, Mr. Captain, to create an environment in the cockpit in which your subordinates feel comfortable telling you what’s going on.

“The same thing needs to happen in medicine from the doctor to the nurse, right on down to the technician who draws blood.”

Other key differences helped aviation make the transition to a safety culture. In contrast with the privacy of the operating room, all airline accidents are public events. Two independent agencies are responsible for air safety—the Federal Aviation Administration regulates flying and safety procedures, while the National Transportation Safety Board investigates every accident. Furthermore, a confidential reporting system, set up almost 25 years ago, enables airline workers to report dangerous situations promptly and without penalty.

The reporting system helped to standardize procedures to the maximum extent possible. “The importance of standardization has a lot of subtle implications that are nonexistent in medicine,” Rutherford says. “When one airline learned a lesson, the whole industry learned a lesson.”

|

||

Something the medical industry already is borrowing from aviation is the use of simulators for training, which is a program Rutherford will oversee at the patient safety center. Anesthesia, in particular, has embraced in recent years the use of simulators for teaching basic skills. Simulation is now so advanced that it’s almost like practicing on a real person and doesn’t carry the risk of harming someone. Rutherford says it’s a great way to build teamwork and leadership training across all levels, from the medical student to the resident to the nurse. And unlike real-life emergencies, all the elements of the case are clearly defined. Mistakes cannot be explained away because almost all simulations are videotaped.

Many experts believe a major reason that a safety culture developed early in aviation is that pilots’ lives are on the line along with those of their passengers. Rutherford says he would like to see a health care system in which “I am as comfortable going into a hospital or sending a loved one into a hospital as I am sitting in the back of a commercial air carrier in this country.”

Can medicine make the needed changes to become safer? The UM/JMH Center for Patient Safety intends to become a national role model, and its director believes the timing has never been better. “This center could not happen without national interest in the last few years,” Barach says. “But it’s not going to happen overnight. Moving to a culture that focuses on transparency, reporting, systems, and safety takes time—five to ten years—but we absolutely can get there.”

Barach believes that when good systems are in place, people will do good things. “Right now we have a lot of systems that don’t stop people from doing wrong things, not because they’re malicious but because of thoughtlessness, forgetfulness, or even tiredness. Simple solutions are things like taking potassium chloride off the hospital floors altogether because patients are almost never harmed by no potassium, but a lot of patients have been harmed by too much potassium.”

![]() ubarsky

and Barach envision the safety center having

a University-wide impact. Lubarsky,

who has a business

degree,

sees implications

for the School of Business Administration

as its operations experts work

on patient

flow and other logistical issues, not to

mention the economics of safety. He says the College

of Engineering could be

instrumental in designing

biomedical equipment that helps prevent mistakes.

ubarsky

and Barach envision the safety center having

a University-wide impact. Lubarsky,

who has a business

degree,

sees implications

for the School of Business Administration

as its operations experts work

on patient

flow and other logistical issues, not to

mention the economics of safety. He says the College

of Engineering could be

instrumental in designing

biomedical equipment that helps prevent mistakes.

“Safety is about collaboration and expanding the initiative into every corner of the medical center and the University,”Lubarsky says. “We don’t have a culture of safety in medicine, but we’re going to have to get it. It takes someone to lead, to say it over and over again for ten years before it sinks in. I see this center’s creation as a great investment by the University of Miami and Jackson Memorial Medical Center.”