|

|

|

||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

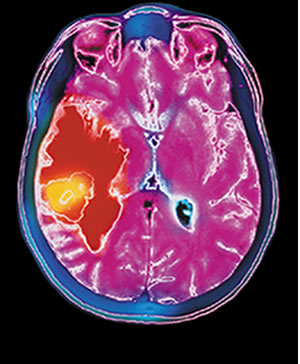

The cause remained a mystery. “Nothing appeared on my MRIs,” she recalls. “Until one day, boom, the tumor appeared.”

It was diagnosed as a malignant glioblastoma, a particularly merciless form of brain cancer that claims more than two-thirds of its victims within five years. Patients who are treated and whose brain tumor reappears face an even graver prognosis; many lose their fight for life within months.

After absorbing the devastating diagnosis, Hartmann, who was 49 at the time, had some difficult decisions to make. The first was where to seek treatment. “I decided I wanted to stay in Miami,” she says. “Then it was the question of ‘What do I do?’”

|

|

Roberto C. Heros, M.D., co-chair of the Department of Neurological Surgery at the School of Medicine, had a novel suggestion for Hartmann. It was a unique chemotherapy treatment—a wafer that is actually implanted in the brain when the tumor is removed. It had been approved by the FDA the year before for use only in cases where other treatments had failed and the patient had suffered a recurrence.

Hartmann didn’t fit the existing protocol, but Heros thought she might be a good candidate for an “off-label” use of the Gliadel Wafer. It was the first time he had considered it.

“She was a relatively young patient at the time and she was in good physical condition,” Heros says. And her tumor wasn’t irregularly shaped, another critical factor. So he told her about his plan to deliver chemotherapy to her brain immediately after her tumor was removed.

Off-label use of the Gliadel Wafer was extremely unusual at the time Heros suggested it for Hartmann. “I knew there were risks about the insertion at the time, the surgery, the irritation, but I was willing to take any chance,” Hartmann says. “They told me they had had very good experience with the wafers after recurrence, so I agreed immediately. When you’re 49, you do what you have to do—you do everything. Four days later, I was home.”

![]() ore than five years later, Hartmann is still disease-free,

a remarkable testament to the power of the implanted chemotherapy. “I haven’t had a recurrence,

thank God, and no side effects. And I didn’t even notice the wafer.”

ore than five years later, Hartmann is still disease-free,

a remarkable testament to the power of the implanted chemotherapy. “I haven’t had a recurrence,

thank God, and no side effects. And I didn’t even notice the wafer.”

In the procedure, up to eight Gliadel Wafers are implanted by neurosurgeons directly into the brain cavity left by the excised tumor. Wafers can be cut to cover every area of affected brain tissue. The wafers remain inside the cavity after surgeons close, then they “bathe” the residual tumor area with high-dose chemotherapy, delaying and even helping to prevent recurrence in many patients. In an international multicenter trial with 240 patients enrolled, those who received Gliadel Wafers and radiation therapy were five times more likely to survive the next three years than patients who were not treated with the wafer.

“Mrs. Hartmann was the first newly diagnosed patient we treated

this way,” says

Heros, who has implanted the wafers in about 20 more patients during

their initial surgeries. Of those, Heros remembers only two recurrences.

“Mrs. Hartmann was the first newly diagnosed patient we treated

this way,” says

Heros, who has implanted the wafers in about 20 more patients during

their initial surgeries. Of those, Heros remembers only two recurrences.

Early treatment of glioblastoma is critical because “we know tumors can become more resistant over time,” says Deborah O. Heros, M.D., a medical oncologist in neurology at the University of Miami Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center and the wife of Roberto Heros. “New tumors are more susceptible to chemotherapy.”

Last spring, the FDA changed the standard of care for the Gliadel Wafer and approved it as a frontline treatment for newly diagnosed malignant glioma patients. Roberto Heros, who is the immediate past president of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, and Deborah Heros hope this change will open new possibilities to surgeons, medical oncologists, and patients. “Previously, patients would present to the emergency room, be whisked away to surgery, come in to their oncologist, and ask for the Gliadel Wafer,” says Deborah Heros. “After the surgery, it is too late.”

Adds Hartmann, “I have spoken with many people who weren’t aware of the Gliadel Wafer. If more patients knew about it, I’m sure they would try it.”

Data from the National Institutes of Health show that each year in the United States more than 18,000 patients are newly diagnosed with malignant brain gliomas, including more than 10,000 with high-grade gliomas. Now as many as two-thirds of newly diagnosed high-grade glioma patients could be eligible to receive the Gliadel Wafer during their initial surgery.

![]()

oberto Heros sees tremendous

potential for patients nationwide to benefit from the change in FDA

approval. “Undoubtedly the use will increase

exponentially.” He believes it also may ease one of the greatest

burdens for any surgeon. “At the time when you have to give the

family the bad news that a tumor was malignant, it is nice to be able

to give

at least some good news that we were able to use the wafers at surgery

and, as we speak, the chemo is now beginning to act on whatever tumor

cells may remain.”

There are three other advantages to the surgically implanted wafer: It circumvents the body’s natural cerebral defense that often prevents traditional intravenous chemotherapy from reaching the brain; it eliminates side effects of systemic chemotherapy, like hair loss and nausea; and it administers chemotherapy immediately. Traditionally, patients don’t begin IV chemotherapy or other treatments until they recover from surgery, which may take up to two weeks.

Despite the success with the Gliadel Wafer, Hartmann’s care didn’t end with her surgery. “I did systemic chemotherapy. I did radiation therapy for almost a year.” She also is on a daily regimen of medications to prevent seizures, medicines that sometimes rob her of energy—but not for long. “Your outlook is also very important. I’m a very positive person and I think that helps a lot. When I came home from my surgery, my mother thought I was going to put on my pajamas but I put on my sneakers and jeans,” Hartmann recalls.

“I would have no hesitation about recommending the wafers. I think they played an important part in my whole treatment,” says Hartmann. “Surgery is your first chance to fight back.”

FDA approval of the Gliadel Wafer for new patients will make it a much more common weapon in that fight. “We do what we think is best for the patient,” Roberto Heros says. “Nothing else matters.”