|

|||||||||||||

undreds of children and adults are followed in the comprehensive program,

which was started in the mid-1980s and is now recognized as one of the

best in the United States. In many instances UM helped pioneer the way

childhood cancer patients are treated and followed long-term.

undreds of children and adults are followed in the comprehensive program,

which was started in the mid-1980s and is now recognized as one of the

best in the United States. In many instances UM helped pioneer the way

childhood cancer patients are treated and followed long-term.

“People first thought of having long-term survivor clinical programs about 20 years ago primarily because it wasn’t even until the late 1970s that you started to see an increasing number of children who were treated for various malignancies become survivors,” says Stuart Toledano, M.D., who heads the clinic and is director of the Division of Pediatric Hematology/ Oncology in the Department of Pediatrics at the Miller School of Medicine.

|

||

|

|

|

“We started to recognize a unique set of problems and late effects of their treatment, both medical as well as psychosocial, in this group of children and young adults who had survived cancer. And frankly there was no information in the literature about this group of patients because before long-term survival was rare. These kids would be the first generation to survive in large numbers, and they would go on to teach us everything we know, and their experiences impact how we treat children diagnosed today with cancer.”

The current treatment for Hodgkin’s disease resulted directly from the lessons of this first generation of childhood survivors. Mediastinal radiation, or radiation to the chest, was once considered the gold standard for treating children with Hodgkin’s. But years later physicians at long-term survivors programs started seeing young men with shorter-than-normal torsos.

“We found radiation in kids has a very specific side effect and that’s the effect on growth. A lot of these kids received their radiation before puberty and their chests stopped growing,” Toledano says. “I would have to explain to them, ‘You can work out all you want, but because of the radiation, your chest is not going to expand.’ It seems so simple now, but we had no way of knowing before, because so few lived long enough for us to find out.

“With girls we saw the same sort of thing, but it took longer. Ten to 15 years after radiation they were developing a lot of breast cancer, but only in the middle part of the breast, where they received the radiation for their Hodgkin’s. Because of these experiences, today we use chemotherapy for Hodgkin’s and avoid radiation altogether in most patients, with the same survival rate.”

A study recently published in the journal Pediatrics by Steven Lipshultz, M.D., professor and chairman of the UM Department of Pediatrics, found that long-term cancer survivor clinics are among the best places to conduct studies on the late effects of childhood cancers, particularly cardiovascular complications caused by cancer treatments. “Doing these kinds of studies on long-term survivors helps us pick up not only serious medical problems, but trends as well, issues such as employment, psychological problems, and even insurance concerns,” says Lipshultz. “These programs, if run properly, are very effective at helping us identify a multitude of potential physical, psychosocial, and economic problems among cancer survivors.”

Children who come to Toledano’s survivors program hear pretty much the same story, from the first day. “I always tell them, ‘I don’t know why you got cancer, but you did.’ But the point is, there are very few alive today who had childhood leukemia in the 1950s and ’60s, and we are just now seeing a large number of people who have survived more than 20 years, so we have no idea what you can expect when you reach your 40s and 50s. It’s uncharted territory.

“So I tell them to do what they can to live a healthy lifestyle. Avoid risks, avoid heavy drinking, absolutely do not smoke— whatever it is that makes you pre-disposed to cancer, avoid. For example, if you’ve survived a myeloid cancer, it’s probably not a good idea to become a house painter and be around a lot of fumes. Why would you want to work around those kinds of things when you don’t know what caused your cancer the first time?”

s children survived longer and longer, more late effects of their cancer

treatment became evident. One of the biggest areas of concern has been

the impact of treatment

on how a child learns. Daniel Armstrong, Ph.D., associate chair of the Department

of Pediatrics and director of the Mailman Center for Child Development, has

been at the forefront internationally of studying the cognitive effects

of cancer

treatment.

s children survived longer and longer, more late effects of their cancer

treatment became evident. One of the biggest areas of concern has been

the impact of treatment

on how a child learns. Daniel Armstrong, Ph.D., associate chair of the Department

of Pediatrics and director of the Mailman Center for Child Development, has

been at the forefront internationally of studying the cognitive effects

of cancer

treatment.

“We knew when we looked at the first leukemia survivors in the late ’70s and early ’80s, virtually all had significant learning problems, and very few were over 5 feet tall because the radiation stunted their growth and interfered with growth and development of their brain,” remembers Armstrong. “Most of these first kids, over time, would have a decline of 20 to 70 IQ points. It was disastrous.”

|

||

|

It was imperative for researchers to figure out how the treatments were affecting the developing brain. They began to see that the parts of the brain and functions that developed before treatment were relatively intact, but it was a different story for the part of the brain that developed after treatment.

“We did a study in babies under 3 who received high dose radiation for brain tumors, and they had problems in all areas—almost all were in the mentally retarded range, some severely, with lifelong severe disabilities,” explains Armstrong. “But what we found is if we could give chemotherapy and delay radiation until age 4, we got about a 20-point increase in their IQ, and that makes the difference between a child who can learn and one who cannot.”

This work led Armstrong’s team to develop a model that’s been reliably predictive of the impact treatment at a specific age would have on future learning. The most sensitive time for the brain is before birth, while the first three years are the second most crucial time, when gross motor ability and language develop. That’s why radiating a child before age 3 has such devastating effects. The primary development between ages 3 and 7 is in the frontal part of the brain, which is involved in attention, visual memory, speed of processing, and ability to organize and plan. After age 7 the impact of treatment on the brain is not as severe, but the front part of the brain does continue developing into the mid-20s.

“By about 1990 we could identify the impact of treatment on learning, but there were no interventions,” Armstrong remembers. “We could delay radiation, reduce some chemotherapy, but those treatments were associated with good survival, so most parents believed it was better to have a child with a learning problem than a dead child.

“I started working with a series of children having school-related problems and they are really the ones who get the credit—I just recognized the pattern. What I began to see is that these children treated before age 7 for brain tumors could learn when the information was going in their ears and coming out their mouths. But school is a read/write world, not a listen/speak world.”

Armstrong’s team started developing an accommodation plan for these children that shifted them to a listen/speak way of learning: books on tape, dictating their assignments on a tape recorder, voice-recognition software, and other technology. Of the ten children they initially worked with, who at the time met the criteria for special education and mental retardation, nine have graduated from high school with a regular diploma, five have been American Cancer Society college scholarship recipients, and one has graduated cum laude from Florida Atlantic University.

|

||

|

|

|

“What we are working on now is a cognitive rehabilitation model that we can utilize during treatment, when the injury is happening, and drive through the injury by exercising the brain,” Armstrong says. “Where a child with cancer is today, the child of tomorrow won’t be there. They’ll be better. All of our concern when we first started was acute care: How do we keep these kids from dying? Now the shift is clearly how do we lessen the late effects, how do we treat the consequences of our successes? We don’t know the answers, but we’re going to find them because we have the chance to.”

As with many things in medicine, the first hint of late effects of cancer treatment in children came through observation. “I was taking care of children as a cardiologist in the mid-1980s, and I started seeing kids with serious heart problems, and I would look back and see they had been treated with chemotherapy,” recalls Lipshultz. He published the first large study to show a link between late cardiac effects in children treated with doxorubicin (Adriamycin®) for ALL in childhood. Lipshultz estimates there are now more than 2,000 papers on late cardiac effects that show increasing rates of heart failure, cardiac transplantation, and cardiac death in young adults previously treated for childhood cancer.

But much like the cognitive late effects, the focus is now shifting to how to prevent the problem in the first place. A study published in The New England Journal of Medicine by Lipshultz last summer could have huge implications for the thousands of children diagnosed with cancer every year.

More than 200 children newly diagnosed with high-risk ALL were enrolled in this multicenter, randomized, controlled trial, conducted out of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. Half of the children were treated using the standard multi-agent protocol for ALL, which includes doxorubicin. The other half were treated with an infusion of dexrazoxane (Zinecard®) 30 minutes before receiving doxorubicin. Dexrazoxane is a free-radical scavenger that has been found to protect the heart of adults receiving the same type of chemotherapy.

“The dexrazoxane therapy was associated with a large and statistically significant reduction in heart damage in the children who received it before their chemotherapy,” Lipshultz says. “Receiving the dexrazoxane had no impact on the effectiveness of the chemotherapy in the short term; longer follow-up will determine the influence of dexrazoxane on survival and heart function.”

wenty-three-year-old Meital Cohen of Miami received

high doses of Adriamycin when diagnosed with high-risk leukemia just

before her 7th birthday.

Just over a year off treatment, she relapsed. She would come very close

to death

before

a bone marrow transplant saved her life after a seven-year struggle.

Cohen visits the survivors clinic, but she doesn’t dwell on the possibility

of cardiac problems down the road.

wenty-three-year-old Meital Cohen of Miami received

high doses of Adriamycin when diagnosed with high-risk leukemia just

before her 7th birthday.

Just over a year off treatment, she relapsed. She would come very close

to death

before

a bone marrow transplant saved her life after a seven-year struggle.

Cohen visits the survivors clinic, but she doesn’t dwell on the possibility

of cardiac problems down the road.

“I watch myself, I get my annual checkups, but I don’t worry about it. Everyone’s life has problems, but I live a normal life like everyone else,” says Cohen. “Cancer doesn’t mean death—there is life after cancer, and I intend to enjoy it.”

|

||

|

A key area of new research is finding ways to keep kids with heart damage healthy. One way is through exercise, but it is not known which cancer patients would benefit from it most. Tracie Miller, M.D., director of clinical pediatric research at the Miller School of Medicine, is looking at genetic mutations of mitochondrial DNA that may have been damaged in children undergoing chemotherapy. “The mitochondria is the powerhouse that produces energy and is found in every cell in the body,” explains Miller. “If you damage the DNA you could actually impair the mitochondria from producing energy. So if you’re asking a muscle to work, with not enough power you could do more harm than good.”

Miller’s research team has been looking at children who received an anthracycline, such as Adriamycin, to see if they have more genetic mutations in their mitochondria, then determine if those with more mutations don’t excel as well with exercise. “Our work has shown that childhood cancer survivors are at risk for a sedentary lifestyle, cholesterol problems, decreased bone density and obesity, so we want to promote exercise in some regard, but not at the risk of hurting their heart.”

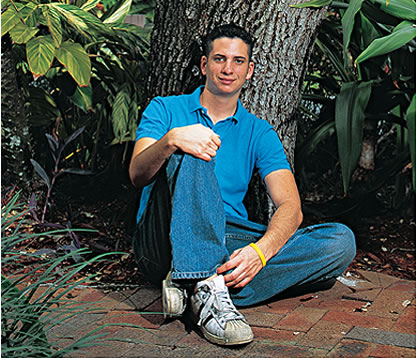

On another warm summer day, 20-year-old Seth Fishman goes for his six-month checkup at the long-term survivors comprehensive program just before returning to Indiana University for the fall semester. At 15 he was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease, but because of the children who came before him, he received no radiation, only chemotherapy. He’s new to survivorship—but as part of the second generation of childhood survivors, he’s grateful to those who came before him and knows he has a role to play.

“You worry that something might go wrong, it’s always in the back of your mind, and you’re certainly not ever going to forget it,” says Fishman. “That’s why it’s important to come back and get checked and help stay on top of any problems that could crop up. Cancer gives you a different outlook—you savor every moment of your life.”

Aviel Sanchez is making the most of his life. Married for six years to his high school sweetheart, he’s just been promoted to sergeant in the Miami-Dade County Police Department, an agency he has served for more than ten years.

Meital Cohen recently received her degree in architecture from the University of Miami, and is already working on a development project. She hopes the doctors and nurses who cared for her never forget how grateful all the survivors are.

“They have a gift to help others, save others,” Cohen says, “especially the children.”

Jeanne Antol Krull is director of media relations in the Office of Communications at the Miller School of Medicine. Photos by John Zillioux and Donna Victor.