|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The school gym is the center of life at Camp Katrina. It’s where the bathrooms and showers are, where supplies are stored, and where each day begins with breakfast and ends with a prayer before dinner.

It’s even where some of the volunteers from Miami sleep during their stay in Long Beach, Mississippi, maneuvering their cots around the rain buckets scattered like chess pieces in the middle of a game. It is three weeks after Katrina and Hurricane Rita is coming, so if it isn’t hot outside that’s only because it’s raining.

Still, the volunteers are far better off than the people they’re treating.

“One of the men we saw was in the greatest storm surge area,

Bay St. Louis, and he and his wife had to go up into the attic to avoid

drowning,” says

Eduardo de Marchena, M.D., professor of medicine at the Miller School

of Medicine and director of interventional cardiology at JMH. “He

kicked out the air vents to go on the roof.” That man lost his

home, survived the storm uninjured, then got hurt helping clean up

his son’s house.

“One of the men we saw was in the greatest storm surge area,

Bay St. Louis, and he and his wife had to go up into the attic to avoid

drowning,” says

Eduardo de Marchena, M.D., professor of medicine at the Miller School

of Medicine and director of interventional cardiology at JMH. “He

kicked out the air vents to go on the roof.” That man lost his

home, survived the storm uninjured, then got hurt helping clean up

his son’s house.

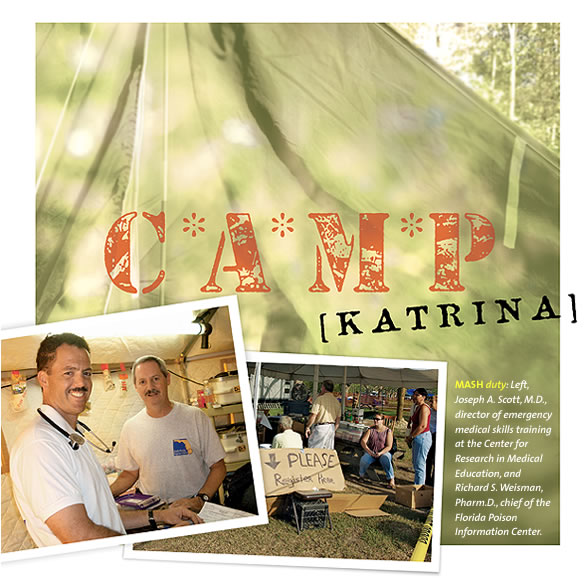

M*A*S*H

![]() ardiologist de Marchena observes

that the family medicine doctor is king in Camp Katrina, but nobody

is really in their element.

They have

had to re-invent health care.

ardiologist de Marchena observes

that the family medicine doctor is king in Camp Katrina, but nobody

is really in their element.

They have

had to re-invent health care.

“Doctors without Orders,” says a sign in the tent.

“We have been very creative and resourceful,” says Elias Vasquez, Ph.D., N.P., F.A.A.N., F.A.A.N.P., associate dean of academic programs, UM School of Nursing and Health Studies. “We know that what we have is what we have, and we need to make the best use of it.”

“Let me put it this way,” says Dodard. “The way we organize stuff here, it’s pretty much the way we do it when we go to [our clinic in] Thomonde, in Haiti.” The medical needs are much the same—trauma and overuse injuries, infections, heat exhaustion, a lack of medications.

“People tell you that they have absolutely no resources, they have nothing left,” says Dodard, leader of the first week’s team. “It’s not just a question of telling them ‘I’ll give you a prescription’—they don’t want to go to any pharmacy or they can’t. So we give them their medications.”

Patients with heart disease and diabetes walk out with clear plastic bags full of medicine, a three-week supply, at the end of a sort of medical assembly line. When they arrive they walk in past one of those enormous, deafening shop fans. It’s jokingly called the privacy fan because nobody at the next table can overhear a conversation between doctor and patient.

Somebody posts the day and date on a piece of cardboard hanging on a tent pole; otherwise it would be hard to keep track. Elementary school desks line the middle of the tent. Seats facing away from the doctors are for people who just arrived—patients facing the docs have been triaged and are ready to be seen.

Army private Trent Barber is here for a tetanus shot after he cut his arm cleaning up—but then almost everyone who walks in gets a tetanus shot. It looks a lot like where people get flu vaccines at the grocery story, with a handwritten “Tetanus” sign hanging on a picnic table.

A neurosurgery resident and a fourth-year medical student sew up lacerations on the operating table around the corner, behind a wall of supply boxes. In front of the boxes sits a man in his 60s, laboring to breathe through a nebulizer. Breathing problems are common since mold is rampant and the hardest-hit areas smell of diesel fuel, sewage, and decay.

Broken Hearts

he other major need, the one

few locals call by its real name, is psychological counseling. “I

started out offering primary care,” explains Carl

Eisdorfer, Ph.D., M.D., Knight Professor and director, University of

Miami Center on Aging, and special assistant for aging to University

President Donna E. Shalala. “As

soon as they found out that I was there, the mental health problems

started getting referred to me, so after a day or so I was really doing

primarily psychiatry,

and I was constantly busy.”

he other major need, the one

few locals call by its real name, is psychological counseling. “I

started out offering primary care,” explains Carl

Eisdorfer, Ph.D., M.D., Knight Professor and director, University of

Miami Center on Aging, and special assistant for aging to University

President Donna E. Shalala. “As

soon as they found out that I was there, the mental health problems

started getting referred to me, so after a day or so I was really doing

primarily psychiatry,

and I was constantly busy.”

Every caregiver was encouraged to ask patients what they’d been through, but sometimes a simple question, like where did they live, would trigger a breakdown. “I saw so many people I can’t even count them,” says Suzanne Lechner, Ph.D., clinical psychologist, director of psychosocial support and research for the Braman Family Breast Cancer Institute at UM/Sylvester. She pauses for a moment. “They’re so completely devastated emotionally that it is heartbreaking.”

In Camp Katrina, a psychological referral is a simple thing. A clinician simply catches the counselor’s eye and gestures for them with a hand.

“It’s unfortunate that we have to experience a tragedy to really appreciate what we have in our own lives,” says Vasquez of the nursing school. “The lessons learned from the patients that I’ve seen who say ‘I’ve lost everything, however my family is OK,’ and they’re grateful for that—that’s incredible to me, when they have nothing but the clothes on their back.”

Among the UM volunteers are brothers Thomas J. and William J. Harrington Jr., M.D.’s from hematology oncology. They lost their father, William J. Harrington, M.D., during Hurricane Andrew

Answering a Prayer

he patients are universally

grateful for these strangers who left behind air conditioning and

traffic lights and came 800 miles

to sleep

in a

gym—and

to help people they’ve never met.

he patients are universally

grateful for these strangers who left behind air conditioning and

traffic lights and came 800 miles

to sleep

in a

gym—and

to help people they’ve never met.

“I came here because it was nearer than the hospital,” says 73-year-old Juanita Burrows, who was bleeding badly from a cut in her leg. “I’m glad you were here.”

Over five weeks in September and October, 35 people from UM and JMH work in this makeshift MASH unit, treating several thousand patients. Ironically, the last volunteers come home a couple of days before they plan to, on Friday, October 21. They’re afraid that if they finish their weeklong “tour” and stay through Sunday, they might have trouble getting home to South Florida.

Hurricane Wilma is on the way.