|

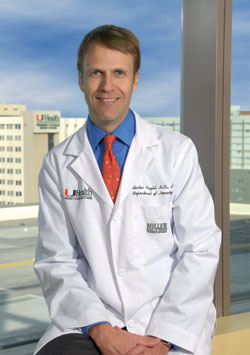

| Clinton Wright, M.D., seeks to unlock

the mystery of the aging brain and how

it relates to memory and other forms

of cognition. |

How many times have you forgotten where you put your car keys—or walked into a room only to forget what you went there for? Do these scenarios sound familiar? When it comes to memory lapses, the big unanswered questions ask what is considered a part of normal aging—

and what is actually the beginning of a disease process.

Clinton Wright, M.D., recently recruited from Columbia University to be the scientific director of the Evelyn F. McKnight Center for Age-Related Memory Loss and an associate professor of neurology at the Miller School, has spent most of his career trying to find the key to unlock the mystery of the aging brain and how it relates to memory and other forms of cognition.

“The purpose of the McKnight Center is to look at normal cognitive aging, but first we have to define what is normal,” explains Wright. “Our research will focus not only on understanding normal cognitive aging, but distinguishing it from Alzheimer’s disease

and other causes of cognitive problems.

“A certain degree of forgetfulness

is normal as we age, such as trouble finding words, remembering names,

not being perfect at recognizing someone whom you don’t know all that well—

but that doesn’t mean you are going

to continue to progress and get worse. Studies show that people who have complaints about memory tend to develop problems later, but there are plenty who do not. We need to figure

out what’s going to happen to someone based on these mild symptoms.”

The Evelyn F. McKnight Center for Age-Related Memory Loss was established at the Miller School through

a $5 million gift from the McKnight Brain Research Foundation in 2003, which required matching funds. The Miller School met the funding requirements through several sources, including the Schoninger Foundation. The Schoninger Foundation’s $3.5 million gift will support the Alexandria and Bernard Schoninger Neuropsychology Program and Clinic and The Alexandria and Bernard Schoninger Professorship in Neurology at the McKnight Center.

In addition to the center at the Miller School, the McKnight Brain Research Foundation has established programs at the University of Florida, the University of Alabama, and the University of Arizona.

|

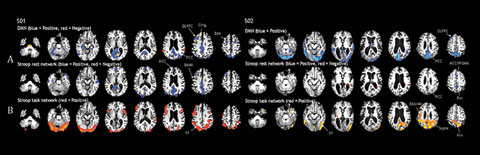

| Functional MRIs showing the default mode network enable researchers at the McKnight Center to study age-related changes in brain connections. |

The centers all have similar missions, but the faculty at each location has different research strengths. “It was a natural to recruit Dr. Wright as scientific director because of his role with the Northern Manhattan Study while at Columbia University,” says Ralph Sacco, M.D., M.S., professor and chair of neurology at the Miller School and the person who established the study in 1990 while at Columbia.

“The Northern Manhattan Study

is the first study of its kind to focus on stroke risk factors in more than 4,000 whites, blacks, and Hispanics living in the same community,” explains Sacco, who also serves as executive director of the McKnight Center. “Five years ago Dr. Wright took a subset of that population, 1,290 people, to study subclinical changes in the brain and how they may relate to cognitive decline or even future stroke.”

None of the participants had ever had a stroke and were relatively normal from a cognitive standpoint. They each underwent MRI scans and cognitive testing and are now being followed over time with repeated neuropsychological testing to see who declines and who stays normal.

“We are very interested in the group that stays normal because that may suggest some determinants of successful cognitive aging,” says Wright. “Already we have gotten some interesting results. A fifth of our population had vascular damage in their brain that never gave them symptoms severe enough to lead them to a physician, and when we looked at their cognitive function we found associations between the presence of vascular damage and decrements in the ability to perform tests that tap specific cognitive functions.

“Even though some with vascular damage had cognitive complaints, others did not. Since we haven’t followed them long enough yet, we don’t know who will get Alzheimer’s, who will have vascular dementia, and who will stay normal. Figuring that out is the key.”

Cognitive impairment caused by vascular damage or vascular cognitive impairment, which can lead to vascular dementia and contribute to Alzheimer’s disease, is a growing area of research because modifiable vascular risk factors can be treated—such as high blood pressure, diabetes, and high cholesterol—and damage thereby prevented.

Since the purpose of the McKnight Center is to look at normal cognitive aging, researchers must first determine what is normal when we age.

“It’s very common to have vascular damage in older people; 78 percent have it in our sample. Maybe that’s normal, and it’s not normal to have squeaky clean vessels in an old person,” Wright speculates. “If so, the question becomes what is the threshold of vascular damage a person can suffer before it seriously affects their cognition?”

In an effort to drill down into vascular risk factors that may affect cognition, Wright examined a

subsample of 656 of his Northern Manhattan Study participants to measure white matter hyperintensities and subclinical infarction and their possible association with cognitive performance.

“The brain is made up of nerve cells, and those connections between the neurons make up the white matter,” Wright says. “Think of the nerve cells as tiny computers, and the white matter as the cables between the computers.

“What we found is that people with a certain amount of white matter damage performed slower on cognitive tests and had problems with cognitive flexibility on cognitive tests compared with those with lower levels of white matter damage.

“White matter damage can be caused by a variety of things, but to the extent

it is caused by vascular damage it can be prevented by controlling blood pressure, sugar levels, and cholesterol, and avoiding smoking.”

The center is supporting yet another research focus that is just getting under way: a genome-wide association study of all 1,290 of the Northern Manhattan Study subset participants. Genetic researchers at the Miller School’s Miami Institute for Human Genomics will be looking at genes related to healthy cognitive aging and vascular cognitive impairment.

“This collaborative research project will help us identify genes that may be associated with early vascular changes in the brain, such as white matter disease,

as well as cognition,” says Sacco.

The McKnight Center plans to facilitate collaborative research projects throughout all levels of the University, whether basic, translational, or clinical, aimed at a better understanding of healthy cognitive aging.

“It would be great if we could keep people thinking as sharply when they are 90 as when they were 20,” adds Wright. “There have to be reasons cognition changes as we get older. We need to figure them out, and then throw a monkey wrench into the process.” |