Dispatches from the Front Lines

Unimaginable anguish and mind-boggling challenges, lives lost and saved, dignity amid desperation, miracles large and small: Members of the Miller School recall indelible impressions and unforgettable moments from their volunteer work in post-earthquake Haiti.

Eduardo de Marchena, M.D. Eduardo de Marchena, M.D.

Associate Dean for International Medicine Chair, University of Miami Medical Group

Miller School volunteers who served in Haiti after the earthquake saved a lot of lives, but we were the lucky ones. We experienced tremendous horror from human suffering, but we also regained a profound understanding of the purpose of caregiving.

When I arrived in Port-au-Prince four days after the earthquake, our large field hospital, the University of Miami Hospital in Haiti, was not yet built, and medical care was being delivered in two United Nations tents packed with hundreds of patients and human agony. Many survivors were wearing the same clothes they wore the day of the earthquake. They had provisional bandages and were inadequately medicated for pain. Many were soiled. They had the assistance of few health care personnel and a small number of family members. The stench of human excrement, infected wounds, and rotting food was everywhere. Flies and mosquitoes swarmed.

|

| Eduardo de Marchena, M.D., in blue scrubs to the left of truck, instructs other volunteers about to transport a patient. |

Yet the patients were remarkably stoic. Most lay quietly with solemn faces, waiting for relief. Those faces, filled with pain yet hopeful, have stayed with me. I remember a young woman who had been trapped under the rubble for six days after her house collapsed on her. She survived because two family members who died on top of her protected her while their crushed bodies decomposed. When she arrived at the U.N. compound, she was severely dehydrated and had significant injuries to her lower extremities. But she was not worried about medical care; instead, she desperately wanted to be cleansed. We really had no facilities to bathe a patient, so we took wet wipes and, with the assistance of the nurses, wiped her down as much as possible to relieve her intense fear of having the remains of dead family on her skin. After she was clean, she was calm and we were able to attend to her lower extremities; she improved remarkably. In another blessing, her mother soon found her in our field hospital.

We also treated a young woman who had been trapped for days in a collapsed mall. She came in with significant crush injuries and severe dehydration. We were working on her on a stretcher at the hospital entrance when a volunteer, a trainee from our Miami medical training program, happened to walk by. She was elated to see the young patient, a close friend whose frantic family feared she had died at the mall. The trainee happily took over care of her friend until she could be transferred to Miami for rehabilitation.

I would return to Miami touched by the beauty of humanity and feeling more complete, as both a physician and a human being.

Joni Maga, M.D. Joni Maga, M.D.

Assistant Professor of Anesthesiology

One of the most challenging days during my time in Haiti was the day we relocated from the U.N. facility to the new University of Miami field hospital. We had overwhelmed the U.N. compound with our volunteers, supplies, and patients, and the relief effort could not expand on those grounds. The U.N. agreed to provide trucks to transport the patients but could not help us move medical supplies.

|

| Anesthesiologist Joni Maga, M.D., performed many roles during her tour of duty at the U.N. clinic and UM field hospital. |

We were fortunate because several U.S. Army soldiers came to us that day asking for specific anesthetics for a hospital in the city that was in dire need. The soldiers had a small truck, so we negotiated its use in exchange for the drugs. I accompanied one of the soldiers, Joey, to show the way and ensure he would return for the rest of the supplies. It took five trips and, even though the new site was only a mile away, nearly 30 minutes each way. The road was lined with hundreds of Haitians, including many children.

With the windows open to relieve the 90-plus degree heat, the truck moved slowly. Frantic people begged for food, water, and work, bombarding the vehicle and thrusting their hands and faces through the windows. Initially I regretted that we didn’t have food or water to hand out. But I began to think that was probably a blessing in disguise, because we would have been mobbed if we had started randomly handing out food and water. It was then that I fully realized the magnitude of despair that had enveloped Port-au-Prince.

Seth Thaller, M.D. Seth Thaller, M.D.

Professor of Surgery Chief, Division of Plastic, Reconstructive, and Aesthetic Surgery

After arriving in Haiti, Dr. Vincent DeGennaro Jr., my former chief resident, found us a ride on a U.N. vehicle, which took us to the provisional tent hospital. Immediately we were overwhelmed by the magnitude and number of injured and lack of supplies. But we were also awed by the energy, enthusiasm, and resourcefulness of the volunteers already there.

|

| A nun asks Vincent DeGennaro Sr., M.D., to help acquire a stretcher. |

We made rounds cleaning wounds and teaching fathers to change their kids’ dressings. I noticed some plaster and began removing an array of improvised splints and creating plaster ones with the few rolls I found. Two nuns managed to get through security and suddenly appeared in our tent. They had hidden injured people under blankets in their van and brought them for treatment. After two more runs, they asked us to commandeer a stretcher so they could lift the injured more easily into their van. With the help of U.N. security personnel, we helped the nuns “borrow” the stretcher.

As they rode off, I turned to two team members and said, “I can’t believe we helped them snatch the stretcher.” My compatriots, both good Catholics, informed me that, because we were working with nuns, it wasn’t considered “snatching.” With the “loaned” stretcher, the nuns continued to bring injured people to our hospital.

Antonia P. “Toni” Eyssallenne, M.D., Ph.D. Antonia P. “Toni” Eyssallenne, M.D., Ph.D.

Internal Medicine-Pediatrics Resident

When I arrived in Haiti with a medical team two days after the quake, we had no nurses and limited medications. Everyone was in pain. Everyone needed immediate attention. Our triage system evolved from red and yellow dot stickers to writing on the patients to writing on scrap paper and taping it to the cot. In some cases, we taped it to the patient. Sleep was impossible. There was too much need: crush injuries, open fractures, pelvic fractures, facial and internal traumas, wounds so severe they seemed unreal.

|

| From top: In the first days, doctors tend patients in the U.N. tents without nurses. A patient is moved to UM’s new field hospital with her hand-written chart taped to her chest. |

In the midst of the chaos, more help came with an international flavor. Physicians from Martinique selected critical patients to evacuate to their island; the Dominican Republic took in a few as well. Those on death’s door were evacuated to the United States. The Israeli military came in like ninjas and quickly set up a fully operational tertiary care field hospital; they also took some of our patients. Doctors, nurses, and medics from Colombia and Portugal came to lend a hand.

As the days progressed, more physicians came in from Miami and all over the United States. It was incredibly moving to see such an outpouring of support for this traumatized country. We received new patients as fast as we evacuated others; they were dropped off by the dozens by ambulance, pickup truck, or other vehicles. The patients included children burned by boiling food, water, or oil in pots overturned by the earthquake. Lungs were collapsing, pelvic fractures were causing urinary retention, and people of all ages were unable to move—some just their legs; others their arms too. We lost several patients that first week, some old, some young—all heartbreaking.

Nathalie Dauphin McKenzie, M.D. Nathalie Dauphin McKenzie, M.D.

Gynecologic Oncology Fellow

I arrived in Port-au-Prince ten days after the earthquake and, just before I left four days later, was fortunate to deliver the first baby born at the University of Miami’s field hospital. The mother had been in labor the entire night, and we tried to make her as comfortable as possible without any anesthesia. She did a great job. When I saw the baby’s head coming, I felt a rush of adrenaline. Finally the baby emerged and let out a cry. Suddenly the entire OR staff and other random volunteers surrounded us and applauded, some teary-eyed, all rejoicing in a moment of happiness.

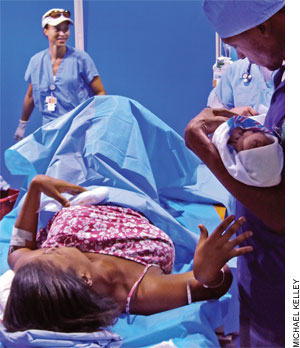

|

| Nathalie Dauphin McKenzie, M.D., delivers the first baby born at the University of Miami field hospital. |

Amid so much pain, moments of joy were few. My dad lives in Haiti, and seeing him was one of those precious moments. He was fine, so—as thrilled as I was to see him when he came by the hospital—I had only an hour to spare for his visit. I could not bear to be away from my patients any longer. I knew they needed me more, so I kissed my dad goodbye and went back to work. He understood.

Every couple of hours helicopters dropped off wounded people by the dozen, and we worked day and night in a shared desire to do all that was possible to make things better. I felt I was no longer just an OB/GYN physician. I comforted a recently orphaned toddler in pain from a fractured femur, and the team brought blankets and food to patients who had not eaten in days. Particularly heartbreaking were the severely wounded children who called out in agony for their parents, not knowing their moms and dads had died in the quake. Equally hard was having to make room for more incoming casualties by watching patients whom we had finished casting or debriding limp back to the street on crutches, with no home or family to go to.

Michael A. Kolber, M.D., Ph.D. Michael A. Kolber, M.D., Ph.D.

Professor of Medicine Director, Comprehensive AIDS Program

Director, Adult HIV Services For my five-day tour, I, along with other doctors at the University of Miami Hospital in Haiti, wanted to care for the large number of individuals in need. Everyone worked long hours; personnel resources were limited. No one complained. During my first day, six nurses needed intravenous fluids because they had not taken the time to drink or eat.

|

| Security officers keep order among the anguished. |

A medical barter system was in play: Someone from one medical facility would take these patients if they could have some of those supplies. It was commonplace and it worked—driven by the volunteers’ common goal to help all the patients.

But there were those we could not help, like the 26-year-old man with congenital bullous disease of the lung. He was unable to provide enough oxygen to his body and needed a lung transplant or a bilateral upper lobectomy. He was transferred to a local hospital.

|

| A rescue worker transports a well-bundled newborn. |

A premature baby was delivered by Cesarean section, but there was no incubator. So pediatricians kept her warm with the heating element from an MRE (military Meals Ready to Eat). Even with that effort, she got worse and needed to be intubated. There was no respirator so the pediatricians alternated bagging her on an hourly basis before she was transferred to another facility.

Even now I marvel at how people from so many different states and countries worked together for a common good.

Michael Kelley, MBA Michael Kelley, MBA

Vice Chair for Administration University of Miami Medical Group

In Haiti, I saw more death in one day than I had seen in my entire life. I would wake up with corpses of the victims who died the night before placed next to me. Yet those visions do not haunt me. Instead, I see the faces of the wounded who would have died, had the impossible not occurred. I see the enthusiasm of caregivers asked to do the unimaginable. I see the woman with a freshly amputated leg, singing songs of praise to God.

|

| An injured survivor writhes in pain as doctors prepare to move him from a truck. |

“A miracle a minute” was the catchphrase we used again and again.

The very existence of a 25,000-square foot tent facility erected and staffed in a virtual war zone by volunteers is miraculous in and of itself. After all, the University of Miami isn’t a first responder. Yet we were on the ground before governments and organizations that spend millions on disaster preparedness.

We have no mobile medical facilities, yet in a few days we built the largest operating hospital in the region. We had no stockpiles ready to ship, yet we overflowed our tents and swamped a section of the airfield with donations to feed countless survivors and supply legions of medical teams with the essentials needed to treat thousands of patients.

We are not an airline, yet we transported hundreds of volunteers to Haiti at no cost.

I am not haunted by what I saw. I was witness to a miracle.

Thomas Johnson, M.D. Thomas Johnson, M.D.

Professor of Ophthalmology, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute

I was part of an ophthalmology team organized by Richard Lee, M.D., associate professor of ophthalmology. We arrived in Haiti with medical supplies and a goal to assess the need for ophthalmology intervention, then perform any emergent eye or facial surgeries. Our first night, we confronted harsh reality. I held a flashlight for a trauma surgeon while he amputated a gangrenous arm on a concrete slab outside one of the medical tents at the U.N. compound.

|

| Ophthalmologist Thomas Johnson, M.D., comforts a 2-year-old orphan whom the ophthalmology team took under its care. |

The next day we rounded on more than 200 patients to evaluate ophthalmic injuries. Most eye-related injuries consisted of infected lid and facial lacerations. On our third day, we set up a makeshift ophthalmology and wound-care clinic between the hangers. Tom Shane, M.D., had previously organized an eyeglass library, and we brought several boxes of ready-made glasses with us.

|

| Johnson examines a patient who had been trapped for days under a collapsed market. |

The clinic was open to inpatients, family members, and relief workers. We tested vision, used the autorefractor to determine lens power, and distributed glasses, eyedrops, artificial tears, and vitamins. Word quickly spread, and soon we had a long line of patients. At the end of the day, we had examined and treated over 140 patients. Many had lost their glasses and eye medications in the quake. We changed dressings on facial wounds. There were a lot of smiles and laughter, and the clinic provided a welcome respite from the prevailing chaos, suffering, and agony.

Ashlee Vainisi, M.S.N., FNP-C, CCRN Ashlee Vainisi, M.S.N., FNP-C, CCRN

Oculoplastics Nurse, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute

Haiti was a completely surreal sensory overload—I experienced sights and smells that I will never be able to erase from memory. We were lucky enough to have been stationed in the U.N. compound, which, awful as it was, was far better than the danger and filth many unfortunate Haitians were experiencing. I believe I will easily be able to conjure up the sickly smell of the air and hear the cries that I heard in those tents 20 years from now.

|

| The sun rises over the burgeoning UM camp. |

Heading to the camp, it was odd to fly over a country at night and not see city lights. Compared to the bright lights of Miami, seeing only fires and a few emergency generators was frightening. In the morning, it was hard to reconcile the beautiful sunrise over the mountains with the sight of small children with missing limbs. The nights were equally unnerving—very quiet except for muffled sobbing and an occasional peppering of bloodcurdling screams.

|

| From left: A volunteer organizes supplies. Ophthalmology resident Thomas Shane, M.D., checks the eyes of an earthquake survivor. |

Haiti was at once one of the best and one of the worst experiences of my life. Giving back in a time of need is truly a blessing. You learn a lot about people’s tolerance for bad times. You learn a lot about yourself. And you learn how good canned sardines taste after a long day without food.

|