Sheri Flamenbaum was thrilled to discover

she was pregnant with twins in 2001. She was devastated

two years later

when her twins were referred to the Debbie School at the

University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. The twins

were diagnosed with developmental delays and hypotonia,

or floppiness. At age 2 1/2, Haley was at the level of

a 15-month-old child; Alec was like an 8-month-old. “A

little knowledge is a dangerous thing,” says Flamenbaum.

All the former physical therapist and UM alum knew of the

Debbie School was the classroom it had for profoundly disabled

children—and she was terrified to think that “my

children belong there.” But “once I got into

the Debbie School, it was the most wonderful experience,” Flamenbaum

says. “Everybody there, from their teachers to the

bus drivers to the custodians to the administrators, loves

and knows every child by name. My children had the best

of everything—the best therapists, the best programs,

the best education. I knew nothing about the Debbie School,

and I’m now one of its biggest cheerleaders.” The

path to the Debbie School was different for

another mother. After seeking second and

third and fourth opinions,

Carladenise Edwards was eager to send her son, William,

to the school for its Auditory/Oral Education Program.

The toddler had been diagnosed with moderate to severe

bilateral hearing impairment and started attending the

Debbie School’s summer camp. “We saw progress

the first week,” says Edwards. “He really

started to communicate, and we’ve kept him there

ever since.” Now 3, William is enrolled in the

program full time and continues to improve his communication

skills. “He’s

receiving therapy every day,” Edwards says. “Our

only other option was to send him some place where he would

receive therapy once a week. There just aren’t

enough therapists to go around.”

Joining William at the Debbie School

is his 16-month-old sister, Zora. The “typically developing” child

is also thriving at the school. “She’s building

self-esteem and confidence and leadership skills. I’m

really pleased with her progress,” Edwards says.

The Debbie School (also known as

the Debbie Institute) “is

one of the gems of the Mailman Center for Child Development

and the Miller School of Medicine,” says Daniel Armstrong,

Ph.D., professor and associate chair of the Department

of Pediatrics and director of the Mailman Center. “Parents

of children who go there gush about their child’s

experience, regardless of whether the child has a disability

or not.” A higher than average teacher-to-student

ratio, coupled with early intervention research, training,

and service, make the school popular for parents of

both typically developing children and children with

disabilities.

The enthusiasm doesn’t end when the child leaves

the Debbie School. There are few research/service programs

like the Debbie School that inspire gratitude for more

than 20 years,” Armstrong says.

The Debbie Institute was built in

1972 to house early education programs for young children

with disabilities.

The institute

conducts research on problems impacting children with

special needs and provides early intervention services

for children

and their families. It also offers training for University

students interested in careers ranging from special

education to physical therapy. The institute is a designated “demonstration

school” where students from many different disciplines

come to research and learn different techniques and faculty

members apply different models of teaching gleaned from

research. Originally called “laboratory schools,” demonstration

schools are the “scientific arenas in which professionals

experiment with new ideas that advance teaching and learning,” notes

Rebecca Fewell, Ph.D., who directed the Debbie Institute

from 1991 until her retirement in 2002.

The results of research studies

from demonstration schools are often key to shaping

public policy. In

1975 education

for students with disabilities began to change with

the passage of the Individuals with Disabilities Education

Act (IDEA). A National Education Association publication, NEA

Today Online, reported that as late as the mid-1970s

an “estimated one million kids with disabilities

didn’t even attend school. For disabled children

who did attend school, special education usually meant

placement in a special class or a special school.” A

series of amendments to IDEA in the 1990s mandated

moving children with disabilities into classrooms with

typically

developing peers.

The Debbie School was one of the

first schools that provided “a

model for early intervention for young children with disabilities,

which was then transitioned to Miami-Dade County Public

Schools and is now known as their Prekindergarten Program

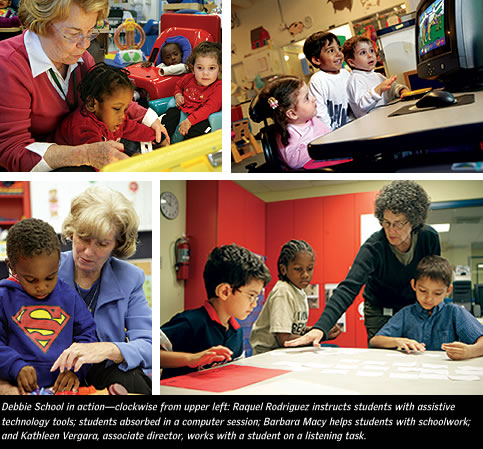

for Children with Disabilities,” says Kathleen Vergara,

associate director of the Debbie School. The school was

one of the first in the country to research—and then

advocate—placing both typically developing children

and children with special needs in classrooms together.

It was a hard sell at first. “Parents of children

with disabilities thought teachers would only pay attention

to typically developing children, and parents of typically

developing children thought their children would imitate

the children with disabilities,” Vergara says. A

generation of children has now grown up “comfortable

with children with disabilities and their differences.

And the gains for children with disabilities have been

greater than predicted,” Vergara says.

Vergara heads a staff of about 60

who serve the school’s

three separate programs for children.

The Early Education Program serves

80 children with developmental disabilities from birth

through 3 years

of age with their

peers. The program includes six “inclusion” classrooms

as well as one self-contained classroom for children

with severe disabilities.

The Auditory/Oral Education Program

serves 35 children who are deaf and hard of hearing

from 12 months to

8 years of age, and the Infant-Toddler-Preschool Education

Program

has approximately 45 typically developing children

between

the ages of birth through 5. Families pay tuition to

support those services—the Early Education and Auditory/

Oral Education programs are supported by contracts with

Miami-Dade County Public Schools and Children’s Medical

Services, while summer services are funded by The Children’s

Trust.

“The Auditory/Oral program is also an inclusion

program,” says

Vergara. “The children are together from the

time they’re 1 until they move out into kindergarten.

The more time they spend together, the closer they

become.”

Alec and Haley Flamenbaum were referred

to the Early Education Program after having been diagnosed

with

more than a 25

percent deficiency in one or more areas. They became

eligible for fully funded education from the State

of Florida. “To

me, it was a handout, and that had a stigma,” admits

Flamenbaum. “I thought I would be treated differently

because I wasn’t paying, but I never felt out of

place—it always felt like home.

“But the most important thing is the quality of education

and the care they received,” Flamenbaum says. “The

amount of disabilities these children come in with

and overcome because of the school’s stellar

staff is incredible.”

In addition to its educational programs, the Debbie

School is engaged in several studies designed to improve

the education

of both disabled and non-disabled children. Among those

projects is the DEB-Tech Project, originally funded

by the Health Foundation of South Florida, which is

developing

a model program on providing up-to-date assistive technology

for special needs children who are educated in inclusive

classrooms with their typically developing peers.

Vergara says the DEB-Tech Project

helped create guidelines for the best practices in

assistive technology usage

in classrooms. Through funding from The Children’s

Trust, the Debbie School has expanded the DEB-Tech

Project by

providing workshops on how to use assistive technology

at child care centers throughout Miami-Dade County.

Outside of the Debbie School, students and teachers

from all over the state benefit from its research,

including

former pupils.

After attending the school for a

year, Alec and Haley Flamenbaum are now almost 6 years

old and in kindergarten

at a Miami-Dade

public school. They come back to the school every year

for summer camp. Their mother obviously still holds

the school dear: “My husband and I may have created our

beautiful twins, but the Debbie School gave us the children

they were meant to be,” she says.

|