James Orovitz thought he was in the best

physical shape of his life. He was 60 years old and enjoyed

normal blood pressure and low cholesterol. Still, he

felt a little odd.

“I went to my family physician for my annual physical,

and I brought a list of symptoms with me,” says

Orovitz, whose complaints included slower and stiffer

walking, illegible handwriting, and a soft, hoarse voice. “I’m

the kind of person who smiles a lot, and it just felt

difficult to smile,” he says. His doctor diagnosed

Parkinson’s disease. A neurologist tested Orovitz

with a surprise backwards push. “I just lost my

balance totally,” Orovitz says.

The National Parkinson Foundation (NPF)

was there to pick him up. Another beneficiary of NPF

is Bernard J.

Fogel, M.D., now dean emeritus at the Miller School

of Medicine. Fogel’s personal connection dates from

the early 1960s, when he was serving as assistant dean

of medicine and recognized that his father was suffering

from Parkinson’s.

“Back then it was a pretty obscure disease,” he

recalls. “I would bring my father to the NPF, which

was adjacent to the medical campus, for treatment three

times a week.”

Fogel says his father’s regular visits made a big

difference. “The major thrust of his care consisted

of physical therapy and massages. But the consistency

benefited him in many ways beyond medication. It allowed

him social interaction with other people suffering from

the disease, he felt the therapeutic modalities were

very beneficial, and it permitted him to get out of the

house in an independent manner.”

Parkinson’s disease is a motor system disorder

that occurs when dopamine-producing brain cells die or

become impaired. It is named after James Parkinson, the

London physician who in 1817 was the first to describe

the disease in “An Essay on the Shaking Palsy.” Well

over a century later, in 1957 Jeanne C. Levey founded

the National Parkinson Foundation to help her husband

who suffered from the disease. In the 50 years since,

it has become the largest and oldest organization of

its type in the country.

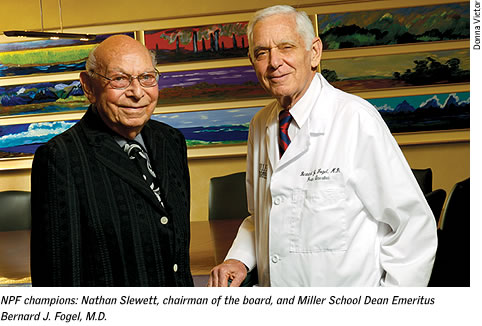

Levey nurtured the NPF until her death

at 92 in 1979, when the directors turned to board member,

businessman,

and attorney Nathan Slewett, who became president and,

later, chairman of the board.

The University of Miami’s relationship with the

NPF began at the same time through the efforts of Slewett,

Fogel, Harold Kravitz, Sidney Schreer, and Herb Zemel.

The partnership led to sharing of medical expertise and

emphasized patient care. “Under the terms of the

agreement,” says Slewett, “the medical school

moved the entire departments of neurology and neurological

surgery into the NPF building and agreed that these clinicians

and surgeons would be the ones to take care of all our

Parkinson’s patients. We also established a unique

clinic that provided physical, speech, occupational,

and recreational therapies, which became a national model.”

Perhaps most importantly, Slewett, who

at 94 years young continues his relationship to the institution

as a daily

volunteer, says, “It was also agreed that every

patient would be treated regardless of their ability

to pay.”

The foundation’s mission is threefold: to determine

the cause of Parkinson’s and ultimately find a

cure; to improve the quality of life of patients and

caregivers; and to educate the patient, their caregivers,

health care professionals, and the general public about

Parkinson’s disease and its treatment.

“The NPF’s relationship with UM was a giant

step in our history because it gave us credibility,” says

Slewett. “About three years after our partnership

started, the foundation created Centers of Excellence

that provided clinical care and outreach. We now have

54 centers all over the world.”

The centers are designed to act as regional “hubs” for

Parkinson’s disease research, care, education,

and outreach. They also offer innovative models of service

such as the Allied Team Training for Parkinson’s,

a one-of-a-kind interdisciplinary training program specifically

designed for allied health and nursing professionals

across the country.

“It’s unique because most training programs

have very little emphasis on Parkinson’s disease,

which is a very complex, idiosyncratic disease,” says

Ruth Hagestuen, R.N., M.A., director of field services

for the NPF in Miami. “We teach the cutting-edge

treatments in such areas as physical therapy and speech

pathology. These services, when delivered properly, can

make an enormous difference.”

When it comes to clinical care, the physicians

in the UM-NPF Division of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement

Disorders are at the forefront of diagnosing the disease,

setting up treatment, and developing appropriate therapies. “We

see patients in every stage of the disease,” says

Carlos Singer, M.D., professor of neurology and division

director.

Singer says that Parkinson’s does not just attack

motor skills. “For instance, sleep, diet, and depression,

gastrointestinal problems, and blood pressure problems

also arise. We try to establish if their symptoms are

linked to the disease or not.” He says that listening

to patients and helping them cope with the unknown is

key. “We acknowledge their fear and see if we can

allay it by reassuring them and educating them. Patient

education is very important because it empowers them.”

For some patients, surgery can also be

an option. Bruno V. Gallo, M.D., assistant professor

of neurology, and

Jonathan R. Jagid, M.D., assistant professor of neurological

surgery, use electrodes to perform deep brain stimulation.

A patient’s brain functions are measured to see

whether he or she would be a good candidate for surgery,

a procedure that modifies the behavior of the “trouble-causing” cells.

At any given time, Parkinson’s patients can take

advantage of dozens of clinical trials that are under

way to test new medications that are not yet publicly

available. Community outreach is also a big part of the

UM-NPF partnership. Nurse practitioner Angela Russell,

A.R.N.P., Ph.D., has a patient practice at Saint Catherine’s

Rehabilitation Hospital in North Miami. “This has

allowed us to establish contact in the community with

the purpose of focusing on the issue of treatment and

sharing information,” explains Singer.

For more than two decades, the Miami Brain

Endowment Bank housed at the NPF has worked on unlocking

the mysteries

of the human brain. Under the direction of Deborah

Mash, Ph.D., professor of neurology and the Jeanne C.

Levey

Professor of Parkinson’s Disease Research, the

bank is one of the nation’s largest collections

of postmortem tissue from patients who have willed their

brains to science. Researchers probe the tissue for clues

to the causes of brain-related disorders and diseases.

This vital center at the National Parkinson’s Foundation

is providing answers from a new frontier. “We’ve

long suspected an environmental link to these illnesses,

but now we think there is a complex interplay between

the genes and the environment,” says Mash, who

is now working closely with the acclaimed genetics team

that recently came from Duke University to the Miller

School. Margaret Pericak-Vance, Ph.D., has identified

genes critical to neurological illnesses. Her husband,

Jeffery Vance, Ph.D., M.D., chief of the Division of

Human Genetics, is a world leader in the genetics of

Parkinson’s disease.

Vance says conventional wisdom about the

disease has changed radically in recent years.

“James Parkinson, in his famous monograph describing

the disorder, considered that ‘lying on the damp

ground’ could

contribute to the development of Parkinson’s disease,” says

Vance. “While we consider this a bit humorous today,

the environment as the primary if not the only cause

of Parkinson’s disease was in favor until as little

as ten to 15 years ago.

“Today we know that genetic mutations in several genes

[Parkin, Leucine Rich Repeat Kinase (LRRK2), a-synuclein,

PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1), and DJ1] can

all cause Parkinson’s disease, each by themselves.

But these mutations represent only a small percentage

of the folks suffering from the disease. It is currently

the belief that most patients develop it through an interaction

between variations of certain genes and the environment.

This complex genetic picture is one which we are just

beginning to unravel.” “Today we know that genetic mutations in several genes

[Parkin, Leucine Rich Repeat Kinase (LRRK2), a-synuclein,

PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1), and DJ1] can

all cause Parkinson’s disease, each by themselves.

But these mutations represent only a small percentage

of the folks suffering from the disease. It is currently

the belief that most patients develop it through an interaction

between variations of certain genes and the environment.

This complex genetic picture is one which we are just

beginning to unravel.”

It’s an exciting time for Parkinson’s research

and the NPF. Just ask James Orovitz. In the decade since

he began treatment, Orovitz—a generous NPF donor

who serves on the board of directors’ executive

committee—has been managing his illness with four

medications that have slowed the disease’s progress

so he can continue to play golf and “live a very,

very normal life.”

Orovitz partially attributes the successful

management of his disease to NPF’s support groups. “They

provide perspective—one day you may find someone

who is doing better than you, and the next day you might

find someone who is much worse. In the end you come to

the realization that you are what you are, and you accept

it and live with it. There are a lot of good days.” |