The deadly medical mystery that rocked Panama

last September began innocuously, with a trickle of patients

complaining of

weakness and tingling in their legs. Within a matter of weeks

Panama was grappling with a health crisis that claimed scores

of lives until inspired sleuthing by a University of Miami-trained

physician brought the dying to an end. The deadly medical mystery that rocked Panama

last September began innocuously, with a trickle of patients

complaining of

weakness and tingling in their legs. Within a matter of weeks

Panama was grappling with a health crisis that claimed scores

of lives until inspired sleuthing by a University of Miami-trained

physician brought the dying to an end.

Nestor Sosa, M.D., brilliantly fulfilled the

promise that gained him entry into the Miller School’s prestigious William

J. Harrington Medical Training Programs for Latin America, currently

celebrating its 40th anniversary. A Harrington trainee in the

late 1980s, Sosa “was one of our best and brightest,” says

Mark Gelbard, M.D., associate professor of medicine.

Sosa, 45, has received international acclaim

for discovering that diethylene glycol, a poisonous substance

used in antifreeze,

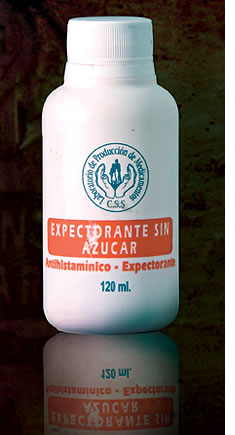

was unwittingly mixed into 260,000 bottles of Panamanian cough

medicine. The diethylene glycol was manufactured in China,

where it had been labeled 99.5 percent pure glycerin, a sweet

compound

used in foods and drugs. Both substances are sweet-tasting

and viscous.

Prior to the deaths in Panama, unscrupulous

Chinese businessmen had knowingly substituted diethylene glycol

for more expensive

glycerin in other

countries, with deadly results.

That wasn’t on Sosa’s mind in September, when patients

experiencing weakness and tingling in their legs began showing

up at the Panama City hospital where he worked as an infectious

diseases specialist. The facility, Caja de Seguro Social/Complejo

Hospitalario Metropolitano, is part of Panama’s social

security system. Sosa was asked to investigate the malady, which

medical researchers had erroneously identified as Guillain-Barré syndrome,

a rare neurological disorder.

That’s because the initial stages of diethylene glycol

poisoning mimic Guillain-Barré syndrome, an often fatal

autoimmune disease with no known cause or cure. But Guillain-Barré was

quickly ruled out when the patients in Panama began to also suffer

kidney failure. By early October the death toll was in the low

teens before eventually peaking at a reported 426 fatalities.

In the midst of a desperate search for a killer,

Panama’s

Health Ministry declared a national epidemic. Sosa notified officials

at his hospital that the mysterious malady was killing roughly

half its victims, and the Panamanian government asked him to

establish and lead a medical task force.

Because 19 of the 21 patients who came to his

hospital were older men, Sosa wondered if aphrodisiacs might

be behind

the deaths.

But that hunch didn’t pan out. Most of the deceased were

over 60 and suffered from hypertension and diabetes. Half had

been taking a blood pressure drug called lisinopril, so as a

precaution Panamanian pharmacies were banned from dispensing

the medication. However, tests showed the drug to be safe.

Sosa’s tenacity finally began to bear fruit following the

admission of a heart attack victim to his health care facility.

While hospitalized, the patient came down with the mysterious

ailment.

“It was obvious that whatever was causing

his problems had to be on the medication list,” Sosa

says.

The patient had been administered several drugs,

including lisinopril. One of its potential side effects is

a persistent

cough. A short

time afterward, Sosa heard of a patient in a private Panamanian

hospital who’d presented Guillain-Barré symptoms

after being given lisinopril.

“What really broke the case was when Nestor

heard about that patient who wasn’t in the social security

system,” says Gordon

Dickinson, M.D., professor of medicine and chief of infectious

diseases at the Miller School. “When that patient showed

up, Nestor jumped in his car and went to interview this patient

in another hospital.” “What really broke the case was when Nestor

heard about that patient who wasn’t in the social security

system,” says Gordon

Dickinson, M.D., professor of medicine and chief of infectious

diseases at the Miller School. “When that patient showed

up, Nestor jumped in his car and went to interview this patient

in another hospital.”

While there, he noticed a half-empty bottle

of cough syrup issued through the social security system. “He didn’t belong

to the social security health care system, but he wanted to save

money, and the syrup was free,” Sosa recalls.

On October 10, 2006, Sosa arranged for several

bottles of the cough syrup to be flown to the United States,

where they

were

analyzed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

in Atlanta. The following day, United States health care

officials informed Panama that the cough syrup had been contaminated

with

diethylene glycol.

Successfully tracking down the killer that terrorized

Panama filled Sosa with mixed emotions. “I was happy because we

found the cause, and we knew that was the beginning of the end,” he

says. “On the other hand, we knew it was something we had

manufactured, that had actually been made in a lab in my hospital.”

The Panamanian cough syrup tragedy triggered

an uproar among a citizenry already furious with a social security

health

care system infamous for not having enough medication and

long waiting

lists for surgeries.

“This was a major blow to the social security

system,” Sosa

says. “There is an investigation going on that’s

not finished, along with a public outcry to take out the

minister of health. Because of the notoriety from this I

got another job.”

After working for Panama’s social security health care

system for 14 years, on April 1 Sosa took a position training

Central American health care workers. Panama’s social security

system claims 79 people died and 119 were affected by the adulterated

cough syrup. The Panamanian district attorneys’ office,

however, puts the death toll at 426.

Sosa’s role in identifying diethylene glycol as a mass

killer is the crowning achievement thus far in a life marked

by an uncompromising quest for excellence.

Born in Camaguey, Cuba, Sosa and his family

moved to Panama when he was 9. He enrolled in the University

of Panama in

1980 and

graduated six years later with a medical degree. A knack

for chess resulted in him being named a national master of

chess

in 1982 and national chess champion of Panama the next year.

Following graduation from the University of

Panama, Sosa completed an internship at his former place of

employment,

Caja de Seguro

Social/Complejo Hospitalario Metropolitano, followed by a

month-long clinical rotation at the Copenhagen Komune Hospital,

where

he focused on internal medicine.

Thinking several steps ahead, like the chess master he is,

Sosa thought it would be useful to train at UM under the

auspices of The William J. Harrington Medical Training Programs

for

Latin

America.

Sosa did three years of residency training followed by a

two-year fellowship in infectious diseases. Gelbard, who

directed the

Harrington residency program when Sosa attended, recalls

that he “was curious and had a thirst for knowledge.”

Attributes that would save untold numbers of

Panamanian lives.

|