She’s 12, wears her long hair in neat cornrows, and

already has some serious risk factors for cardiovascular

disease—high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and

too many extra pounds from a sedentary lifestyle and high-fat

diet. “There aren’t any kids in my

neighborhood, so I’ve just been watching a lot of

TV and eating stuff that’s really bad for me,” says

Angela, the Miami-Dade County sixth grader who is participating

in a research program at the Miller School of Medicine’s

Department of Pediatrics. She is learning how to exercise

more and eat better. About one-third of the nation’s

children and adolescents are overweight or obese, and for

some minority groups the rate is much higher. Since obesity

is considered the second leading cause of preventable disease

and death in this country—second only to tobacco

use—hundreds of thousands of children are facing

an uncertain future. “We have a whole generation

of kids who for the first time may not live as long as

their parents,” says Steven Lipshultz, M.D., chair

of pediatrics and associate executive dean for child

health, who has assembled a diverse team of clinicians

and researchers

to try to change that. The team literally is writing

the book on assessing and preventing cardiovascular risks

in children, having been asked by the American Academy

of Pediatrics (AAP) to contribute chapters on preventive

cardiology, high blood pressure, and heart failure to

the AAP textbook on pediatric primary care.

“This is the very first AAP textbook

on pediatric primary care, and they asked us because

we’re recognized

as being really unique in the country,” Lipshultz

says. “There are very few places that are trying

to document not only how significant cardiovascular risk

is at a young age, but to come up with interventions

that make a difference.”

UM has one of the largest cardiac rehabilitation

programs for children and a team of people who specialize

in cardiology,

nutrition, psychology, gastroenterology, epidemiology,

exercise physiology, and endocrinology—all working

together as a group. “It’s a multifactorial

set of issues that require a multidisciplinary approach,” Lipshultz

notes.

In addition to its work on weight and

obesity, the team also is working on prevention of other

cardiac risk factors,

including exposure to secondhand smoke.

“Certainly the risks are higher than they used to be,” says David

A. Ludwig, Ph.D., professor of pediatrics and epidemiology and public health,

whom Lipshultz calls “among the best in the country at assessing childhood

risk and prevention.”

Although experts speculate that the long-term

effects of obesity and other cardiovascular risk factors

in children will have dire consequences later in life,

Ludwig feels

ongoing research is essential. “At present, definitive longitudinal data

supporting such speculations is limited.” Although experts speculate that the long-term

effects of obesity and other cardiovascular risk factors

in children will have dire consequences later in life,

Ludwig feels

ongoing research is essential. “At present, definitive longitudinal data

supporting such speculations is limited.”

Ludwig, who serves as biostatistician

and designer of studies to assess risk, came to the University

in March from the Medical College of Georgia, where he

was co-director of the Georgia Prevention Institute.

“There are an incredible number of issues here. Kids are not getting as

much exercise,” he

says. “They’re not involved as much in free play as was the case

20 or 30 years ago due to the way neighborhoods are structured now. They’re

more likely going to an organized sport like soccer, and if they’re not,

they’re in front of the TV.

“One of the biggest culprits is

the availability of cheap fast food. We actually have

a surplus of food in this country, and when it comes

in the form of fast

food, it’s very inexpensive and high in calories and fat.”

Preventing obesity during childhood is

critical, because habits formed early often last a lifetime.

Research has shown that overweight adolescents have up

to an 80 percent chance of becoming overweight or obese adults, and earlier

onset

of obesity leads to the earlier onset of related illnesses, such as type 2

diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and certain types of

cancer.

About 18 percent of children in this country

are obese, up from 5 percent in 1974, according to a

study published over the summer [June 27] in JAMA, the

Journal

of the American Medical Association. An estimated 60 percent of obese children

between the ages of 5 and 10 have at least one risk factor for heart disease,

the leading killer in the United States, and 20 percent have two or more risk

factors, the JAMA report said.

A number of previous studies at UM and

elsewhere have shown that African-American and Latino

children living in low-income communities are at greatest

risk for

obesity and related health problems. The American Heart Association has issued

a scientific statement saying overweight children and adolescents represent

one of the most important current public health issues

because of the related medical

complications.

In June a committee of health professionals

issued recommendations saying doctors should assess children’s weight and height annually and attempt to treat

overweight kids based on their age, body mass index (BMI), and any related medical

conditions. BMI is a number calculated from a person’s weight and height

and, in general, reflects how much body fat the child has. The AAP, which participated

in the committee’s work, said while there is a lack of research on the

long-term impact of treating overweight children, doctors should still make it

a priority.

“The enormity of the epidemic necessitates this call to action for pediatricians

using the best information available,” the AAP said.

Childhood onset of metabolic syndrome,

which is diagnosed by testing fasting insulin and glucose,

systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and cholesterol

and

triglyceride levels, significantly increases the risk for type 2 diabetes and

cardiovascular disease.

Sarah Messiah, Ph.D., M.P.H., a research

assistant professor in pediatrics and an epidemiologist,

was involved in a study that assessed the prevalence

of the

metabolic syndrome in a clinical sample of 225 children ages 3 to 18. Reflective

of South Florida, the children were largely from minority backgrounds: 66 percent

Hispanic, 24 percent Afro-Caribbean/black, 5 percent white, and 5 percent multiracial.

“We found metabolic syndrome in

20 percent of this clinic sample,” Messiah

says. “The youngest child was only 7 years old. Those kids who were morbidly

obese were four times as likely to have the syndrome compared to kids of normal

weight.”

And the risks for disease are showing

up in younger and younger children.

Messiah and colleagues in another study

looked at 302 children ages 2 to 5 from eight preschools

in Miami-Dade County. Overall, 30 percent of the children

had

a BMI greater than the 85th percentile, which is about 4 percent higher than

the rest of the country. Within some groups of Hispanic children, 39 percent

exceeded the 85th percentile.

During the research, parents were involved

to some degree, she says. “We’d

do a cooking night and they would bring recipes from their ethnic background.

The goal was to keep the ethnicity intact, but make it healthier or as healthy

as possible,” Messiah says.

“Cultural sensitivity is critical to trying to be able to manage this and

educate

people at the earliest stages,” Lipshultz adds.

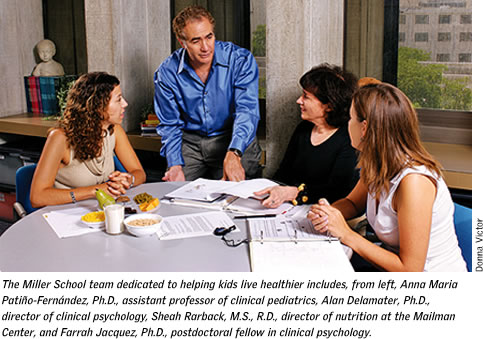

Alan Delamater, Ph.D., director of clinical

psychology and professor of pediatrics, is working with

overweight third and fourth graders at two Miami-Dade

schools

and their parents on a one-year demonstration program. “The work is focused

on metabolic syndrome, which really is a risk for both type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular

disease,” he says. “We’re using the schools as a site because

people are more likely to take part. You can’t expect the working-class

families we’re working with to travel across town to a medical center.”

The study groups are divided into two

comparison groups of 16 or 17 children and their parents. “The more intensive group gets multifamily group meetings

at the school and several individual meetings at the family home,” Delamater

says.

In a small pilot project with five families,

he found them to be cooperative and accepting of ideas

to improve their children’s health. “The parents

and kids both did better, and they’re very responsive and open to having

team members come into the house, sit at their kitchen table, look in their refrigerator,

and talk about what they’re feeding their kids,” he says.

Delamater is collaborating with Sheah

Rarback, M.S., R.D., a registered dietitian and director

of nutrition at the Mailman Center for Child Development

in the

Department of Pediatrics. “With any program, the involvement of the family

is really critical,” Rarback says.

Rarback, who sees overweight children

in her daily practice, explains that just telling children

about the serious diseases they may face in the future

if they

don’t adopt a healthier lifestyle does not bring about the needed change.

“Fear doesn’t work very well. It doesn’t even work with adults.

If

I have a 26-year-old in my office and say, ‘If you don’t lose weight,

you’re going to be diabetic by the time you’re 40’, it doesn’t

work,” she says. “When do they change? When they have the heart attack,

not ten years before they have the heart attack.”

Delamater and Rarback also have another

project with the school system involving 5- and 6-year-olds—not just overweight kids, but all kids. The purpose

of this project is to test the feasibility and efficacy of a school-based, multicomponent

intervention to prevent metabolic syndrome.

“Part of the program will utilize

SPARK (Sports, Play and Active Recreation for Kids),

based in San Diego. They have a whole lot of gadgets

and toys, jump ropes

and things, that can help the teacher get the kids up and moving during the

school day, and that is fun for them,” Delamater

says.

The increase in the youngsters’ physical activity is coupled with creating

a social environment within the schools that emphasizes and values healthy lifestyles.

Other components are based on a tool developed by the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention called the School Health Index, which schools can use to improve

physical activity and encourage healthy eating, as well as prevent tobacco use,

accidental injuries and violence, and control asthma in students who have the

disease. The CDC makes copies of the program available to schools for free.

“Our approach is to work with the principal, the administration, the staff,

the

food-service people,” Delamater explains. “We have a planning grant,

and we’re going to develop the program in one school and have a comparison

school, working with 60 kids in each school.”

South Florida’s richly diverse population also has given researchers the

chance to break new ground studying a Haitian population largely ignored in the

past. Nancy Stein, Ph.D, M.P.H., an epidemiologist and research assistant professor

in pediatrics, is finding they have their own unique set of health issues.

“They may not have anything in common [with other black groups] other than

the

color of their skin,” says Stein, who, along with UM colleagues, has done

the first studies on the Haitian population and is applying for grants to do

more.

Stein says a first step in research is

often to do a medical chart review and collect information

that may generate hypotheses for future funded research.

She says that Lipshultz and Tracie Miller, M.D., director of the Division of

Pediatric Clinical Research in the Department of Pediatrics, both encouraged

her to pursue the research.

“We know that overweight and obesity is everywhere but much higher in the

minority populations. I thought Haitian kids were going to be different because

they all looked thin to me,” Stein says. “But I was shocked, really

surprised, that once they come here they gain weight very quickly, about 4 percent

per year, and in no time it’s the same as if they had lived here forever.

“The bottom line is they gain weight, and that puts them at risk for cardiovascular

disease and other diseases. It shows that the time to intervene is when they

come here. And that’s what we’re going to do next.”

Stein and colleagues are working with

UM’s Center for Haitian Studies to

set up a pilot program to try to prevent young Haitian newcomers from joining

their American counterparts in becoming overweight. Stein says Haitian families

have a complex set of issues that may make it difficult to live a healthy lifestyle.

“These are not the parents who are

staying home and making sure their kids eat well after

school. They’re holding two and three jobs; they’ve

got double minority status; they speak Creole but many

don’t read Creole, so

it’s not a matter of handing them a pamphlet to study.”

Stein found that Haitian adults who immigrate

to the United States weigh 10 to 15 percent less than

average Americans and may close the gap over about ten

years

time. “But for kids, that time element isn’t there. They get immersed

in the whole culture very rapidly.”

Miller, a pediatric gastroenterologist

and professor of pediatrics, says once research shows

results in bringing kids back from the brink of obesity

and all

of its inherent risks, the next hurdle is getting insurers to pay for such

a program. Her research shows that a 12-week active intervention

program, counseling

kids on the importance of a healthier diet coupled with a structured fitness

program, produces results.

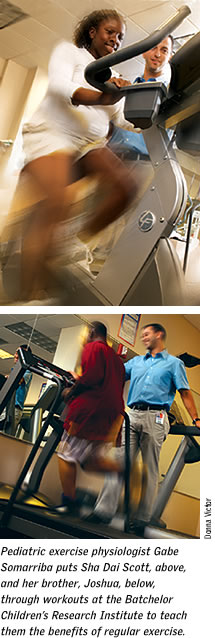

“Our pediatric exercise physiologist, Gabe Somarriba, in the Division of

Pediatric Clinical Research, works with the children twice a week for an hour

and a half,

using aerobic training on a stationary bike, the treadmill, and with weights,

and ellipticals, and as they get stronger he gets them to do more,” Miller

says.

On a recent morning in the gym at the

Batchelor Children’s Research Institute,

Somarriba was putting Angela through an individualized workout. He works with

children as young as 6. They each get baseline blood work, bone density scans,

and other tests that are repeated at three- and six-month intervals to measure

progress.

During the last two weeks of the 12-week

intensive program, Somarriba begins to teach them how

to continue to work out at home and sends them out with

some

dumbbells and a Thera-Band, a stretchy elastic band they can use for resistive

exercises. During the three months the kids are working on their own, he calls

them to provide encouragement and to see how they’re doing. After the three

months, Miller brings them back in to reassess their progress.

“We’ve gotten some good data to show the kids do really well in the

first

three months, and most continue to improve at home but not as dramatically.”

Miller wants to expand the program to

bring in kids from the community whose parents are willing

to pay out of pocket for it. She started talking to HMOs

about six years ago to try to get them to buy into the idea of covering such

a program, but to no avail.

“I keep hoping that with all the focus now on childhood obesity, they will

change

their attitude. I’m trying to prove this would save them money in the long

run,” she says, “but unless you’ve had a heart attack, they

won’t pay for a program such as this that may actually prevent the child

from having the heart attack.”

Nancy McVicar is a freelance writer living in South Florida.

She has been writing about health and medicine for

18 years.

|