|

A smile is on Donald W. Robinson’s lips, but apparently his eyes never got the memo. The Army doctor’s brown orbs are hard and analytical as he addresses a visitor inside his small Army Trauma Training Center (ATTC) office, above the Ryder Trauma Center.

It’s hardly surprising Robinson’s gaze can be steely, given what he’s seen. Like the time he led combat troops into battle in Panama. Or the innumerable occasions he’s patched bodies torn asunder by high-explosive Baghdad booby traps, Miami shootings, and traffic smashups.

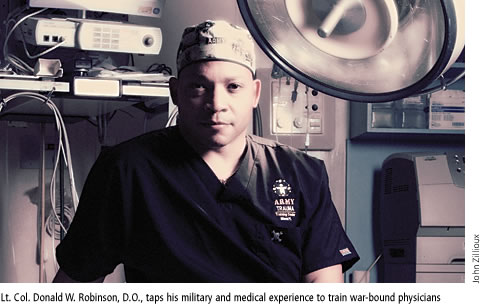

A man who understands carnage from the perspectives of healer and warrior, Lt. Col. Robinson, D.O., 44, is director of the ATTC. He preps Army doctors and nurses for duty in Afghanistan and Iraq by first exposing them to South Florida’s most challenging trauma cases—meaning lessons learned at the Ryder Trauma Center are currently saving lives in Kabul and Sadr City.

Obviously, ATTC personnel don’t encounter injuries caused by roadside improvised explosive devises (IEDs), but they still leave the University of Miami’s medical campus with scads of relevant knowledge, according to Robinson. Obviously, ATTC personnel don’t encounter injuries caused by roadside improvised explosive devises (IEDs), but they still leave the University of Miami’s medical campus with scads of relevant knowledge, according to Robinson.

“I hate to generalize, but a penetrating wound is a penetrating wound,” says Robinson, a man whose sober mien mirrors his responsibilities. “Military doctors and nurses involved with the ATTC program are definitely going to see a lot of gunshot wounds in Miami. So we have a lot of the same things that those guys are going to see when they hit battle zones.”

A collaborative effort between UM, Jackson Memorial Hospital, and the Department of Defense, the ATTC is a win-win for all parties. Miller School of Medicine trainees receive tutelage from combat physicians, Jackson gets an additional trauma surgeon, orthopaedic surgeon, anesthesiologist, and nurses out of the deal, and Army health care professionals get an immersion in high-volume emergency medicine.

Established in 2001, the ATTC is the only program of its kind nationwide. It has a permanent staff of 13, including three Army doctors, five nurses, two medical technicians, one executive officer, and two civilians. Military members of the staff are attached to the ATTC for three years, which is on the longish side as military tours go.

“That’s because it usually takes a year for you to get comfortable and to understand the UM/Jackson system,” Robinson says. “The other thing is, you have to be comfortable teaching because, remember, we’re instructors.”

Robinson went the extra yard and got the credentialing necessary to become a Miller School of Medicine faculty member. His Miller School business card carries the title: Assistant Professor of Surgery, Trauma/Surgical Critical Care.

When he’s not teaching civilian medical students and residents or treating trauma patients, Robinson is training military medical personnel. Army doctors and nurses are assigned to the ATTC for 17 days before shipping out to Afghanistan or Iraq. “Usually we have ten rotations a year, 20 students apiece, so it’s about 200 students a year,” Robinson says. Occasionally, Army medical technicians also go through the program.

As Robinson talks, two things are evident: He enjoys his work and he adores the U.S. Army. His love affair with the Army began while Robinson was an undergrad at Bowie State University, a historically black Maryland college in suburban Washington, D.C.

A student who “was one of those weird people who carried a calculator everywhere he went,” Robinson was a chemical engineering major who joined the Army Reserve Officer Training Corps. Midway through school, he switched his major to pre-med, which precipitated an encounter with biology.

“I got rid of my calculator and started studying biology,” Robinson recalls.

A stint as an infantry officer followed graduation from Bowie in 1987. “Infantry, to me, was fun,” Robinson reveals. “It was like being a big Boy Scout—when nobody’s shooting at you, that is.”

In 1989 Robinson was assigned to U.S. Army Special Operations in the jungles of Panama during Operation Just Cause, the United States’ military action to dislodge dictator Manuel Noriega. Afterward, Robinson found his interest in medicine still burned brightly, so he became a medical services officer.

He left active duty to attend the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, where he earned his degree in 1994. Robinson was beginning a general surgery residency at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey when 9/11 went down. As he and his wife, Shari, watched the day’s events unfold on television, Robinson knew his days as a civilian were numbered.

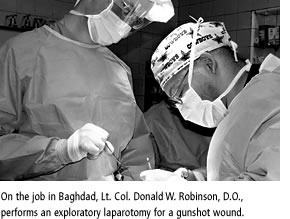

“I’d rather be on active duty,” Robinson solemnly informed his spouse, “because I know a lot of my guys are going to be involved in this in some way.” After reentering the Army as a major, Robinson’s first stop was Fort Benning, Georgia. He asked to be stationed in Iraq and got his wish. From 2004 to 2005, Robinson was chief of trauma at Ibn Sina Hospital in Baghdad, where he received a crash course in emergency medicine.

“Most of the injuries that we saw were IED injuries,” Robinson remembers. “You always hear people throwing out the term ‘polytrauma.’ Well we saw true polytrauma—penetrating, blunt, blast, and burn.” Robinson and his team treated Iraqi civilians along with U.S. military personnel.

When his high-intensity shifts at Ibn Sina wound down, Robinson typically made a beeline for the hospital stairwell, hard rap music thundering from his iPod. “I’d go on the roof and do pushups,” Robinson says of his depressurization regimen.

His next assignment was Miami, where Robinson was promoted to lieutenant colonel and given command of the ATTC. Following hectic shifts at Ryder Trauma Center, instead of hitting the roof, Robinson goes home and plays with his son Kimani, 13, and daughter Karina, 5.

When his ATTC tour ends, Robinson says he’ll gladly return to Iraq if needed. “I’m arrogant enough to believe that no one can take care of patients better than I can,” Robinson laughs, his eyes twinkling this time. |