A heart attack had slowed him down, but Rodolfo Hernandez was still able to lead his active lifestyle. He still worked in construction; he still repaired boats; and for recreation, he still went fishing for hours on end. Then, a few years later, Hernandez, 59, began to feel bouts of weariness—his arms and legs easily tired, and he was frequently out of breath. This time it was heart failure, and a triple bypass was required to correct the heart disease, which affects about five million Americans. A heart attack had slowed him down, but Rodolfo Hernandez was still able to lead his active lifestyle. He still worked in construction; he still repaired boats; and for recreation, he still went fishing for hours on end. Then, a few years later, Hernandez, 59, began to feel bouts of weariness—his arms and legs easily tired, and he was frequently out of breath. This time it was heart failure, and a triple bypass was required to correct the heart disease, which affects about five million Americans.

For care, Hernandez turned to the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, where he was the first to enroll in a groundbreaking clinical trial led by Joshua Hare, M.D., chief of UM’s Cardiovascular Division. The National Institutes of Health-backed, first-of-its-kind trial is being done to study the effectiveness of directly injecting mesenchymal stem cells into the patient’s heart to repair damaged heart tissue.

“I am very happy,” Hernandez said while recuperating at the hospital a week after the operation. “I’m breathing and walking well again. I can’t wait to go fishing.”

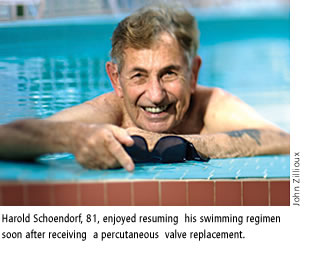

Two other patients, Harold Schoendorf, 81, and Kenneth Horstmyer, 86, saw their heart troubles return about two decades after they both underwent bypass surgery. The diagnosis? In each case, narrowing of the aortic valve—so-called “aortic stenosis.” This time, however, the men’s ages and medical conditions posed considerable risks for second open-heart surgeries.

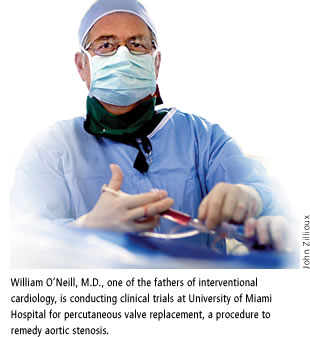

Like Hernandez, Schoendorf and Horstmyer were looking for the most advanced cardiac care. As it turned out, pioneering cardiologist William O’Neill, M.D., the Miller School’s executive dean for clinical affairs, and Alan W. Heldman, M.D., clinical chief of the Cardiovascular Division, were conducting an FDA-approved percutaneous valve replacement trial for which Schoendorf and Horstmyer were perfect candidates. The revolutionary, minimally invasive procedure is available at a handful of medical facilities in the United States and, in Florida, only at University of Miami Hospital.

While Hernandez, Schoendorf, and Horstmyer represent a minuscule fraction of the millions who suffer from cardiovascular disease, Hare, O’Neill, and Heldman represent the Miller School’s team of physicians that is creating one of the world’s most ambitious centers for comprehensive cardiovascular care within UHealth, the University of Miami Health System. While Hernandez, Schoendorf, and Horstmyer represent a minuscule fraction of the millions who suffer from cardiovascular disease, Hare, O’Neill, and Heldman represent the Miller School’s team of physicians that is creating one of the world’s most ambitious centers for comprehensive cardiovascular care within UHealth, the University of Miami Health System.

In keeping with the vision of Dean Pascal J. Goldschmidt, M.D., also a cardiologist, UM’s new Cardiovascular Division is staffed with the most brilliant Miller School faculty in the field who have been augmented by outstanding physicians recently recruited from top cardiovascular programs in the nation.

Joining the cardiovascular team are nationally renowned experts, including Vivek Reddy, M.D., Ray E. Hershberger, M.D., and Gervasio Antonio Lamas, M.D.

“Right now we are at a major transi-tion point in medicine. We are currently reaping the benefits of decades of scientific work that has yielded major new approaches to treating cardiovascular disorders,” says Hare, also director of UM’s Interdisciplinary Stem Cell Institute, where he is conducting innovative stem cell research that has already shown benefits for heart attack patients. “The Cardiovascular Division at UM is dedicated to delivering the highest quality of care to patients while at the same time being on the cutting-edge of new therapies.”

In short, to help meet the nation’s growing heart and vascular needs, the Miller School and University of Miami Health System have created a cardiovascular powerhouse, offering everything from electrophysiology and interventional cardiology at University of Miami Hospital to acute stroke intervention and heart transplantation in partnership with Jackson Memorial Hospital.

“If you take a look at the diseases together, about a million people in the U.S. each year die from cardiovascular disease—heart disease and strokes—and both illnesses increase with age,” says O’Neill. “What we’re assembling here is a first-class team to treat and research all aspects of cardiovascular disease.”

Some of that research will be headed by Lamas, who joined UM in June as medical director of the Coronary Care Unit at University of Miami Hospital and director of the fellowship training program. The internationally recognized cardiovascular researcher is an expert in the design and execution of clinical trials in the fields of coronary disease, heart failure, cardiac pacing, and alternative medicine. Lamas says he is intrigued by UM’s decision to bring together a “critical mass of cardiovascular scientists devoted to developing new solutions for problems in cardiology. I don’t think at this point there is any other place in the country going through such an exciting transformation.”

For Hernandez and other UM patients, the transformation is already helping to extend life.

Deploying Regenerative Stem Cells

Hernandez was the first of 45 patients scheduled to take part in the clinical trial that Hare is leading. In the study, the first to be funded by the National Institutes of Health Specialized Centers for Cell-Based Therapy, stem cells are taken from the patient’s bone marrow and cultured at a UM laboratory. In Hernandez’s case, near the end of his already scheduled triple bypass surgery, the mesenchymal stem cells, or the placebo, were injected directly into his heart.

“The implications for this kind of therapy are enormous when you consider that nearly five million Americans suffer from heart failure and 500,000 new cases are diagnosed each year,” says Hare. “We are very optimistic because we have experimental data that show very clearly the cells we are using do have the ability to turn into new heart muscle cells.” “The implications for this kind of therapy are enormous when you consider that nearly five million Americans suffer from heart failure and 500,000 new cases are diagnosed each year,” says Hare. “We are very optimistic because we have experimental data that show very clearly the cells we are using do have the ability to turn into new heart muscle cells.”

The groundbreaking Phase I/II clinical trial is a double-blind, placebo-controlled study where patients will be randomized to either receive stem cells or the placebo.

Last year, Hare released the results of the first human clinical trial testing the use of mesenchymal stem cells. The study at ten U.S. medical centers was designed to determine the safety and efficacy of infusing adult stem cells intravenously to patients within days of a heart attack to lessen damage to the heart muscle that could subsequently lead to heart failure. Hare, who led the study, concluded that patients treated with stem cells had lower rates of side effects such as cardiac arrhythmia and they had significant improvements in heart, lung, and global function.

Enhancing Minimally Invasive Therapies

UM’s O’Neill, a pioneer in interventional cardiology—which uses catheters to treat heart diseases and excludes the need for open-heart surgery—was the first physician in North America to do a percutaneous valve replacement a half-dozen years ago. Along with Heldman, he is now conducting a Phase III clinical trial at UM Hospital of the percutaneous aortic valve; Schoendorf and Horstmyer were the first and second patients.

Percutaneous valve replacement is seen as a promising option especially for elderly patients who are at high or prohibitive risk for conventional open-heart surgery. The minimally invasive procedure involves crimping the transcatheter heart valve onto a balloon delivery catheter, then threading it through the patient’s circulatory system from the leg.

Compared to open-heart surgery, the percutaneous valve recovery process is remarkably quicker. “The next morning was the most spectacular thing I probably have ever seen in my career in cardiology,” Heldman says. “Both of these guys were sitting up reading the newspaper, asking when could they go home!” Compared to open-heart surgery, the percutaneous valve recovery process is remarkably quicker. “The next morning was the most spectacular thing I probably have ever seen in my career in cardiology,” Heldman says. “Both of these guys were sitting up reading the newspaper, asking when could they go home!”

At a news conference at UM Hospital a week after the procedure, the men were animated and talked about returning quickly to their daily routines.

“I walked about a good half-mile yesterday,” Schoendorf said, explaining that before the valve replacement he was out of breath walking up a flight of stairs.

O’Neill, of course, is not new to working with innovative aids for the heart. He helped develop balloon angioplasty—a procedure in which a thin wire and a tiny balloon are inserted through the groin to open a clogged artery—which is now a standard of care in acute heart attacks.

This kind of expertise and experience in cardiovascular care is growing at UM Hospital, propelled by the enormous resources the Miller School has committed to the program. That’s what attracted Heldman.

“We’re trying to be really transformative in the way we approach some of the most common and most difficult cardiology cases,” says Heldman, who ran the interventional cardiology research program at The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine prior to joining UM last year.

At Hopkins, Heldman did significant work with stents, the breakthrough tiny mesh tubes designed to prop open coronary blood vessels. He was a principal member of the team that did much of the early work developing drug-eluting stents. In his seminal study delivered to the American Heart Association in 1997 and published in Circulation in 2001, Heldman showed that stents coated with the drug paclitaxel performed significantly better than bare metal stents.

Now patients in Miami are benefiting from Heldman’s expertise. Caridad Milanes, an 84-year-old woman with severe hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, is one such patient. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is an abnormal thickening of the heart muscle that can obstruct the pathway for blood to be ejected from the left ventricle and cause symptoms like shortness of breath, chest pain, and sudden loss of consciousness.

Although medication may be effective, some patients, like Milanes, are better served by alcohol septal ablation, the non-surgical procedure Heldman used to relieve her heart obstruction. Milanes is no longer short of breath and has resumed her normal activities since undergoing the procedure in February. “My heart is much better now,” she says. “He saved my life.”

Treating the Electrical System

The Miller School has long had a top electrophysiology team, with patients benefiting from the skills of Robert J. Myerburg, M.D., and other noted experts in the field that treats disorders of the heart’s electrical system.

To build on its already distinguished reputation, the University hired Reddy, a nationally known electrophysiologist, to join the Miller School and treat patients at UM Hospital.

Reddy, most recently director of experimental electrophysiology at Massachusetts General Hospital, a teaching affiliate of Harvard Medical School, recruited a team of top electrophysiology experts to join him in Miami. “We’re building a world-class center specializing in heart rhythm disorders,” says Reddy.

The UM team will focus on using catheter ablation in the treatment of complex cardiac arrhythmia, including arterial fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia. Resynchronization therapies will also be used in the treatment of congestive heart failure.

Enhancing Transplantation Expertise

Although mending hearts is the hallmark of the cardiovascular program, patients whose advanced heart failure necessitates a heart transplant can look to UM doctors for compassionate care with the highest degree of skill in one of the nation’s leading transplantation facilities. And because the need exists in Florida and the surrounding region, UM/Jackson is working on increasing the program’s reach.

The cardiac transplantation program of the Miller School and Jackson Memorial Hospital has been in existence since 1986 and serves as a lifesaving center for patients in the southeastern region of the United States, the Caribbean, and Latin America.

“In over 20 years there have been more than 425 heart transplants with excellent results that are comparable or better than the national average,” says Ray E. Hershberger, M.D., director of the Advanced Heart Failure Therapies Program.

Hershberger, who joined the Miller School last year after 14 years as director of the heart failure and heart transplant program at Oregon Health & Science University, has been working closely with Si M. Pham, M.D., surgical director of heart and lung transplantation, to provide more transplantations. The best programs, Hershberger notes, are “truly collaborative between transplant surgery and transplant cardiology.”

Lifesaving Vascular Therapies

The vascular team, like the heart team, consists of numerous standout physicians who reflect UM’s heavy concentration of “head-to-toe” cardiovascular expertise. “At the Miller School, if you talk about treating from the head down, we have incredible authorities,” says O’Neill. He can quickly list UM doctors who are leaders in every field, such as neurosurgery and neurology, and work alongside teams treating the heart and vascular system.

Among the experts are Omaida Velazquez, M.D., who joined the Miller School last year as chief of the Division of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, and Juan C. Parodi, M.D., professor of surgery in the division. Parodi pioneered endovascular repair for aortic aneurysms, a minimally invasive procedure designed to prevent an aneurysm from rupturing. He also recently devised a system for protecting the brain when stents need to be placed in blocked carotid arteries.

An additional important resource is the new acute stroke center, another joint UM/Jackson partnership that has one of the largest stroke teams in the region. “With new treatment, the window for stroke is widening,” says Ralph L. Sacco, M.D., M.S., an internationally renowned expert on stroke and UM’s Miller Professor of Neurology, Epidemiology, and Human Genetics and chairman of the Department of Neurology. “We can now treat acute strokes and remove clots from arteries with devices that work possibly up to eight hours after a stroke.”

With the growing need for more and better cardiovascular care, university-based systems developing leading-edge therapies are crucial in the fight to save lives. UM’s Cardiovascular Division stands at the forefront.

“What we have here is an impressive team that is moving at breakneck speed to develop a visionary 21st-century medical center,” says Hare, the Cardiovascular Division chief and stem cell expert. “What patients get when they come here is extremely competent service from doctors who are not only on the cutting edge now but who are actively developing the next wave of therapies.” |