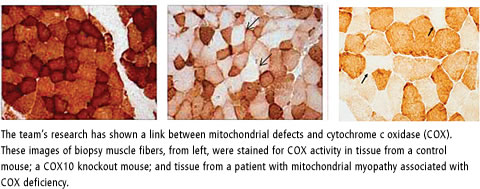

No treatments have been developed for neuromuscular disorders caused by defects in a person’s mitochondria, which affect a large number of children and adults worldwide. A new study by a team of Miller School researchers could suggest a new approach for treating these debilitating disorders.

Mitochondria are specialized compartments present in every cell of the body except red blood cells, and they are responsible for creating almost all of the energy the body needs to sustain life. Most often, mitochondria defects appear in cells of the brain, heart, liver, skeletal muscles, kidneys, and the endocrine system. The defects lead to either cell injury or cell death; depending on which cells are affected, the symptoms may include muscle weakness, cardiac disease, liver disease, and developmental delays.

The Miller School study, published in Cell Metabolism, found that increasing the number of mitochondria in muscle was able to delay the onset and slow the progression of the disease in a mouse model of mitochondria myopathy created by Francisca Diaz, Ph.D., research assistant professor of neurology.

“Our findings showed that we can boost the function of even a defective mitochondrial enzyme by inducing the production of more mitochondria,” says Carlos Moraes, Ph.D., professor of neurology, cell biology and anatomy, and senior author of the study. “It’s a case of more is better—even a defective mitochondrial enzyme in large numbers is better than a small number.”

The researchers were able to increase the mitochondrial levels through genetic overexpression of a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis (PGC-1alpha) or by using bezafibrate, a drug already used in humans with high cholesterol.

“The fact that we can induce mitochondrial biogenesis with drugs that are already in the marketplace should better facilitate the translation of this research to the clinical area,” says Tina Wenz, Ph.D., postdoctoral associate and first author of the study.

Moraes hopes a clinical trial will soon begin to find out how well the medication might work in patients with mitochondrial disorders.

|