|

They are dogged puzzle-solvers. Their quest is for that eureka moment, the next medical breakthrough that may someday lead to a cure for cancer, for heart disease, for Alzheimer’s, for autism.

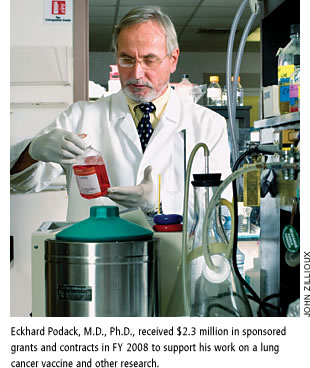

For some, like Eckhard Podack, M.D., Ph.D., and Grace Zhai, Ph.D., the path starts early in life. Podack, son of a physician, was just 16 when he began wondering why cancer came back after surgeons had removed it. Decades later, he is close to controlling lung cancer, the deadliest of all. For some, like Eckhard Podack, M.D., Ph.D., and Grace Zhai, Ph.D., the path starts early in life. Podack, son of a physician, was just 16 when he began wondering why cancer came back after surgeons had removed it. Decades later, he is close to controlling lung cancer, the deadliest of all.

For Zhai, it was the inspiration stirred by her high school biology teacher’s fascination with genetics that set her on a course to solve the puzzle of neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s.

Podack and Zhai, from different generations, and Jennifer McCafferty-Cepero, Ph.D., a researcher turned research administrator, exemplify the goal of the Miller School of Medicine to become one of the nation’s premier research institutions.

Zhai works with the common fruit fly, which shares many of the same genes as humans and may be key to reaching that eureka moment.

Her work at the Baylor School of Medicine in Texas caught the attention of experts at the Miller School. James Potter, Ph.D., professor and former chair of molecular and cellular pharmacology, Charles Luetje, Ph.D., interim chair, and Richard Bookman, Ph.D. vice provost for research and executive dean for research and research training, convinced her to move her research efforts—including her half million flies—to Miami.

Zhai, now an assistant professor of molecular and cellular pharmacology, is among more than 200 medical researchers and investigators who have been recruited in the past two years under the leadership of Miller School Dean Pascal J. Goldschmidt, M.D., known internationally for his own research in cardiology.

Zhai, with flies in tow, arrived at the Miller School in January 2007. Zhai, with flies in tow, arrived at the Miller School in January 2007.

“It’s hard to start something from scratch, but the dean and the chair were really enthusiastic and wanted me to come here, and now I think I made the right decision,” Zhai says. “I arrived with a wave of new researchers, bringing in a lot of new techniques.”

Zhai joins such notables as Margaret A. Pericak-Vance, Ph.D., and Jeffery M. Vance, M.D., Ph.D., world-renowned geneticists who came from Duke University to establish the Miami Institute for Human Genomics; Joshua Hare, M.D., cardiologist and director of UM’s Interdisciplinary Stem Cell Institute, who came from The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine; Marc E. Lippman, M.D., the Kathleen and Stanley Glaser Professor and chair of the Department of Medicine, who came from the University of Michigan, among many others.

Growth of the research effort has necessitated expedited construction of work space throughout the Miller campus: a new nine-story, 188,000-square-foot Biomedical Research Building; the 300,000-square-foot Clinical Research Building on 14th Street; and a 25,000-square-foot, two-story wet lab research building being constructed at the campus’s southeast corner and expected to open in the spring.

“Space is one of our most precious resources,” says McCafferty-Cepero, assistant dean for research at the Miller School. “We are working hard to maximize every nook and cranny of the Miller School campus.” “Space is one of our most precious resources,” says McCafferty-Cepero, assistant dean for research at the Miller School. “We are working hard to maximize every nook and cranny of the Miller School campus.”

McCafferty-Cepero, who trained as a researcher at the Miller School, knows—perhaps more than most in the field—the importance of giving the puzzle-solvers the support they need to pursue their quest. She lost her husband, Henry Cepero, a dedicated cancer researcher, two years ago to a rare form of cancer. They met at the Miller School while sharing bench space just a few feet apart. “My boss used to joke that we would either end up married or killing each other,” she says. “We got engaged in 2003.”

While it was a difficult decision to leave the lab, McCafferty-Cepero decided she could still advance the cause as an administrator and have more normal working hours while she raises their twin daughters, born 10 days after her husband’s death.

Despite personal tragedy, McCafferty-Cepero’s commitment to research is evident in her deep involvement in the multiple projects under way. By supporting the work of new recruits as well as highly successful stalwarts, she is “building an environment for discovery, to make sure all scientists have the tools and creative freedom they need.”

In addition to recruiting top-caliber scientists and clinicians, Miller School leadership has earmarked funds to support innovative and interdisciplinary projects that are in the earliest stages, a move that’s even more important in an era where federal funding is declining.

“We are seeing agencies like the National Institutes of Health (NIH) demanding more evidence of eventual success,” McCafferty-Cepero says. “Ideas that might have been funded several years ago are being dismissed as too risky. That’s why we designed a $600,000 program, the Interdisciplinary Research Development Initiative (IRDI), that encourages researchers from different disciplines to work together on innovative projects.”

Zhai is among the young investigators who applied for IRDI funds in collaboration with Pantelis Tsoulfas, M.D., of The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis, who does similar research using mice, and Gavriil Tsechpenakis, Ph.D., of UM’s new Center for Computational Science, who can track moving particles in nerve cells in real time.

Using the fruit fly, Zhai and a former colleague at Baylor discovered that a naturally occurring protein called NMNAT has neuroprotective qualities and plays an important role in the maintenance of nerve cells. Their findings were published in April 2008 in the prestigious scientific journal Nature.

“The job of this protein is to make everything run smoothly,” she says. “Because neurons are busy firing all the time, damage occurs just like when you’re running your car. Most of the neurons live a lifetime and cannot divide. If you lose one, you have one less. That’s why you see neurodegenerative disease in older generations.”

Encouraging and funding young researchers is important to the Miller School’s goals, as is providing more support for long-established researchers.

Last fall, Bookman and Goldschmidt announced that the research enterprise at the Miller School had reached a major milestone, with researchers bringing in a record $210.8 million in extramural funding for fiscal year 2008. Last fall, Bookman and Goldschmidt announced that the research enterprise at the Miller School had reached a major milestone, with researchers bringing in a record $210.8 million in extramural funding for fiscal year 2008.

Goldschmidt called it “a remarkable testament to our growing research portfolio.”

Fourteen members of the Miller School faculty brought in at least $1 million each in sponsored grants and contracts for the fiscal year. “The majority of that is federal money (from the NIH), but it also comes from other sources, such as the National Parkinson Foundation, the American Cancer Society, and pharmaceutical companies,” Bookman says.

Topping the list once again is José Szapocznik, Ph.D., professor and chair of epidemiology and public health, director of the Center for Family Studies, and associate dean for community development. Szapocznik received about $7.2 million for fiscal year 2008, much of that aimed at making sure the knowledge gained from research in drug abuse treatment gets passed along to community-based drug treatment centers. His work is part of a network of 16 centers around the country established by the National Institute on Drug Abuse to conduct research and promote treatment programs that have been shown to work.

“We have literally changed drug treatment in this country by making the community programs collaborators in the research process,” he says. “There has been a huge movement in the last seven or eight years toward the adoption of evidence-based practice in drug treatment.”

Among other long-established researchers at the Miller School, Bookman cited the work of Podack, Sylvester Distinguished Professor of Medicine and chair of the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, as another prime example of an investigator moving laboratory findings into the real world.

Podack received $2.3 million in sponsored grants and contracts in fiscal year 2008 to continue his work on a novel lung cancer vaccine and other research. And the Miller School and a venture capital firm, Seed-One Ventures, have formed a new company, Heat Biologics, Inc., to develop the vaccine, gp-96, aimed at treating non-small cell lung cancer, the most common form of the disease.

His work has focused on how the body’s immune system cells attack invading cells such as bacteria. Discovering the molecular mechanism, in which holes are punched into bacterial membranes by a single polymerizing molecule, he theorized it might be possible that cells that recognize and attack cancer could use a similar killing mechanism.

“The first experiment went super,” he says. “I could actually see the holes made in the bacteria under the electron microscope. I thought, let’s see if they can make holes in the tumor cells and yes, indeed, beautiful holes in the cell membrane. The pictures ended up in many textbooks and hang on my office wall.”

Podack’s cancer vaccine works in a different way from vaccines used to prevent infectious diseases. He genetically engineered the lung cancer cells to secrete a protein, gp-96, to induce certain immune system cells to attack the tumor.

But the immune system has a braking system that prevents it from overkill and that would eventually halt the work of the killer cells. So Podack went on to develop an antibody that can block those immune regulatory cells, allowing the gp-96 vaccine to remain effective.

“It’s wonderful,” Podack says. “In mice we can implant tumors that would kill them in four to six weeks. If we give them the vaccine, we can save 30 to 40 percent of them, but if we add the antibody to the vaccine, 80 percent survive. Obviously, this is something we want to try in humans, but this takes money from the NIH and other sources. It’s very expensive.”

Bookman says he is proud of the work of both the established researchers and the new recruits.

“There is a wonderful sense among the people who have been here for a while and our new colleagues that we’re doing something special,” Bookman says. “We’re taking a good medical school and making it a great one.” |