Smart

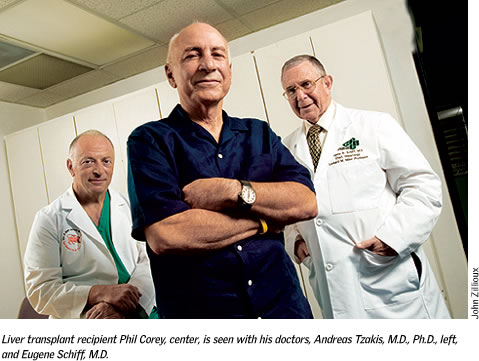

enough to have built a lucrative seafood business

and to have attended medical school, Phil Corey

couldn’t

wrap his brain around the simplest of concepts:

his own mortality. “I was in total denial,” the

68-year-old Coconut Grove resident says of the diseases

that gnawed away

at his liver for 42 years. “I was riding my bike

25 miles a day and had no feelings of being ill.”

Welcome to the confounding world of asymptomatic

liver disease. You feel fit as a fiddle, but at the same

time your doctor somberly warns of cirrhosis, liver

cancer, and ultimately transplantation. Who to believe—your physician or

your body?

Given that he had an entrepreneur’s stamina, along with the energy to pound

around South Florida on his mountain bike, Corey gave the nod to his body. Meanwhile,

the recommendations of his University of Miami medical team were met with skepticism

and resistance.

Hard-driving, opinionated, and stubborn,

Corey laughingly admits that his obstinance occasionally

drove Eugene Schiff, M.D., chief of the Center for

Liver Diseases

at the Miller School of Medicine, “crazy.”

Ultimately Corey had a reality check,

followed by liver transplantation surgery. He’s pledged $3.5 million to the Miller School of Medicine, with $1.5 million

going to the Center for Liver Diseases, transplantation, and gastroenterology,

along with a gift to athletics.

Primarily transmitted through blood-to-blood

contact, the hepatitis

C virus (HCV) popped up on medical radar screens in

the 1960s, an era when intravenous drug use was high

among Vietnam vets and in America’s inner cities.

“We saw almost an epidemic of it,

starting around the time of the

Vietnam War,” Schiff says.

Corey contracted HCV from a blood transfusion

in 1965. HCV is almost exclusively a Baby Boomer

malady in the United States, because effective screening to keep

it out of the nation’s blood supply wasn’t in place until 1992.

That was of no help to Corey, who was

a second-year medical student at West Virginia University

when his lengthy encounter with liver

disease began.

Not aware he had HCV, Corey decided after

two years of medical school that medicine wasn’t his calling. Having already earned a master’s degree in physiological

chemistry from Ohio State University, Corey left the classroom behind and embarked

on a new career in sales. He accepted a position with a meat and seafood importing

firm located in Coral Gables.

In the course of traveling extensively

throughout Latin America, Corey encountered an Ecuadorian

businessman looking to enter

the nascent

shrimp farming industry

and became a partner in the venture. That decision laid the

groundwork for the creation of the Seafood Exchange of Florida

in 1979.

Starting a business

is invariably

a grueling proposition, but Corey had no problem putting

in the long hours required. Because from a physical standpoint,

he felt

great.

That’s a common phenomenon among liver disease patients. A diagnosis of

cirrhosis (scarring) or cancer of the liver is usually the first indication something’s

amiss. When scarring takes place, the liver responds by repairing the damaged

tissue. But sometimes the regeneration process goes awry, leading to uncontrolled

cell production.

In medical terms this is known as hepatocellular

carcinoma, a malignancy that accounts for 80 to 90 percent

of liver

cancers, according

to the National Institutes

of Health. It’s also a cancer with an affinity for men 50 to 60 years old.

By 1982 Corey had become a patient of

Schiff’s and had been diagnosed with

non-A, non-B hepatitis. Still, the prospect of cirrhosis or cancer remained an

abstraction for Corey, even after a CT scan found a questionable growth in his

liver in 2005.

“I went to Gene Schiff with this, because Gene and I have been friends

for so many years,” says Corey, who maintained the whole thing was much

ado about nothing.

“Phil sincerely felt that he didn’t

have cirrhosis and that he didn’t

have cancer,” Schiff says. “Because of

his lifestyle and the fact he was feeling good, he

felt there was a misdiagnosis. We had to really twist

his arm to get various things done.”

The first was a radio frequency ablation

procedure that heated and killed the growth in Corey’s liver. Schiff was assisted by Andreas Tzakis, M.D., Ph.D.,

professor of surgery and director of the Miami Transplant Institute.

The growth was found to contain abnormal

cells, but it wasn’t confirmed

to be cancer. Schiff casually mentioned that Corey might want to contemplate

the possibility of undergoing a liver transplant. The liver specialist had no

way of knowing he’d just thrown down a verbal gauntlet, Corey laughs.

“I said, ‘Gene, I’m not going to have a transplant,’” Corey

remembers. “‘No way in hell am I going

to have a transplant! I’m

too healthy, and I’m not going to worry about

it.’”

But Corey found it impossible not to worry

when another growth materialized a short time later in

a different

part of his

liver.

This time it was unquestionably a “bad boy,” in Corey’s parlance.

A hepatocellular carcinoma. The cancer was ablated, but Corey still wasn’t

ready to come to grips with his condition. A visit to Tzakis changed all that.

“He literally shamed me into getting

a transplant,” Corey laughs. “He

simply said, ‘You gotta get off the damned

fence and realize that these things are gonna keep

coming!’”

Corey reluctantly agreed to have a procedure

done in April. “It was hard

for me . . . I was one of the few liver transplant patients that didn’t

come in here crawling on his hands and knees,” he says.

A successful five-hour operation left

Corey with a month-and-a-half ban on bicycling.

“We’re grateful for his generosity,

and we’re pleased that thus far

he’s had a good outcome,” Schiff says. “The

purpose of the Center for Liver Diseases, and certainly

for me personally, is to keep liver

diseases from getting to a point where transplants

are needed.”

It’s an objective that Corey fully supports, to the point of becoming more

involved with the Center for Liver Diseases and the Miami Transplant Institute.

He views his liver treatments and surgery as “God’s way of steering

me in a different direction in my life,” he says.

“I’m a very religious person.

I believe that this was his way of nudging me toward

what I’m doing now and what I’m going to

continue to do.” |