|

|

Herty Overton had a problem. She was pregnant with her first child and barely out of her second trimester, but her daughter Lauryn was tired of waiting. She was on the way. Now.

“She was born at 1 pound, 13 ounces—at 26 weeks,” says Overton. “She stayed in the hospital for two months.” Lauryn went home in time for Christmas, still tiny—just 4 pounds—but fully formed and healthy. Six years later, Overton was back in the unit with Kimberly, also premature; she also went home healthy. Thirty years ago, both babies would have been too small, too frail; in the 1970s fewer than one infant in five survived being born before 28 weeks.

Now it’s more than four out of five.

“This has been possible only because of the research that has been done in neonatology,” says Eduardo Bancalari, M.D., director of the Division of Neonatology at the Miller School of Medicine. For more than 30 years, a dedicated team, in and outside the hospital, has fought to give the tiniest patients a fighting chance at life.

Nine months. That’s the standard gestation period for a baby, the time for a normal, healthy pregnancy—40 weeks, 266 days. To be sure, most pregnancies go full term. But in the United States, one child in eight—nearly half a million babies—is born prematurely. A child is considered premature if born before 37 weeks. At that period of gestation a “preemie” can still weigh 6 pounds and be, essentially, fully formed.

What about the babies who come at 30 weeks? Or 25? They are barely through the second trimester, may barely weigh 1 pound. Their brains are still developing, their eyes are still closed, and connective tissue is still forming around the bones. And then there are the lungs.

“When I started working there was a rule that no baby under 28 weeks would be ventilated, it was not even attempted,” says Bancalari. That was in the 1970s. “And without ventilating, the chance of survival was zero.” The lungs are among the last organs to fully develop. Oxygen, like everything else in utero, comes through the umbilical cord—babies don’t need to breathe until they’re born, which is supposed to be at 40 weeks. But there are dozens of babies in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Holtz Children’s Hospital, inside Jackson Memorial, who were born at less than 30 weeks. “When I started working there was a rule that no baby under 28 weeks would be ventilated, it was not even attempted,” says Bancalari. That was in the 1970s. “And without ventilating, the chance of survival was zero.” The lungs are among the last organs to fully develop. Oxygen, like everything else in utero, comes through the umbilical cord—babies don’t need to breathe until they’re born, which is supposed to be at 40 weeks. But there are dozens of babies in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Holtz Children’s Hospital, inside Jackson Memorial, who were born at less than 30 weeks.

“Now the survival is 80 or 90 percent,” says Bancalari. “The moment of viability has moved from about 1 kilo in the 1970s to 400 or 500 grams.” Four hundred grams—that’s only nine-tenths of a pound. “It has been incredible,” says Bancalari.

And yet, the battle is still not won.

The Fight Goes On

It was April 2003. Tracy Germani still clearly remembers being in the unit—drifting between two incubators, hovering over her tiny twin boys. After a couple of weeks, Alex—just 1 pound, 5 ounces—seemed to be breathing better than his 3-pound brother, Diego. “We had gone in that Sunday. Alex was a little bit fussy and he got sick,” she recalls. “They started him on antibiotics but said they didn’t know if he was going to make it.”

Alex suffered from necrotizing enterocolitis, a dangerous condition in the digestive tract. After intestinal surgery by Juan Sola, M.D., assistant professor of clinical surgery and one of four faculty members in the Division of Pediatric Surgery, he held on for six weeks.

“But they said the infection was everywhere.” Germani pauses.

“So we held him for an hour, and he died in our arms.”

Necrotizing enterocolitis is a bit of a mystery. It overwhelmingly strikes premature infants. It also happened to be an area of great interest to Mark Rowe, M.D., UM’s head of pediatric surgery in the 1970s. At that time, Rowe wanted to learn more about the plights of these tiny babies. New mom Schatzi Kassal wanted to show her appreciation to the doctor who operated on her son, who was suffering from an abdominal obstruction. Doctor and mother were in the right place at the right time and their partnership led to Project: New Born.

Rowe promised to break new ground in neonatal research and Kassal promised to support him. Both delivered handsomely. Given that this was a new area of medicine 35 years ago, the arrangements were unusual. Rowe’s neonatology lab was at Miami’s Veterans Affairs Hospital, but he was a member of the Miller School faculty and treated babies at Jackson.

Kassal got to work organizing fundraisers and welcoming friends into the fold. Before long, the original “seven babes” of Project: New Born were hosting luncheons, arranging donations, and becoming an essential part of neonatology at UM. In fact, the bevy of tireless volunteers, including lifetime treasurer Peggy Banick, an original “babe,” and lifetime co-president Joslyn Drucilla Miller, have raised more than $10 million—all of it dedicated to neonatology and most of it to research.

And the largest area of improvement, by far, has been in breathing life into tiny lungs.

“The area where Bancalari and his team have accomplished the most is in reducing newborn lung disease,” says Steven Lipshultz, M.D., chair of pediatrics. “And the advances that have come out of the University of Miami have improved care throughout the world.”

In immature lungs the alveoli, or air sacs, are fragile, and a biochemical lubricant—a surface active agent, or surfactant—doesn’t form until the final days of a normal pregnancy. Premature babies can suffer from respiratory distress and pulmonary hypertension, even bouts of apnea. Then breathing just stops.

One of the problems, ironically, was the ventilator. Even with exacting precision, mechanical breathing often injured the lungs, causing inflammation and scarring called bronchopulmonary dysplasia. The use of a surfactant treatment now helps to protect these infant lungs.

An adult doesn’t have to think about breathing—we each take about 20,000 breaths, day and night—a newborn takes more than 40,000. That’s the idea behind mechanical ventilation, except it’s not quite automatic—not yet. But Nelson Claure, Ph.D., is working on it. A research assistant professor of pediatrics and a biomedical engineer, he’s revolutionizing how to help premature babies breathe.

“These babies need supplemental oxygen,” says Claure. “But too much oxygen can be bad for the retinas and even the lungs.” Monitors already track oxygen levels in babies’ blood, then sound an alarm when there’s a problem. For most babies, nurses answer the call and adjust the oxygen saturation.

But for 15 babies who were part of a closely monitored test, the ventilators adjusted themselves—as often as 30 times an hour. Preliminary tests show those babies had just the right amount of oxygen almost every minute of every day.

In extreme cases, the best way to help injured lungs is to bypass them altogether. “For a select population, if they suffer from something that is transient or that can be reversed, for 10 to 14 days we actually put them on something like a heart/lung machine,” says Shahnaz Duara, M.D., professor of pediatrics, and obstetrics and gynecology. “You run the blood through this machine to let the lungs heal.” It’s called EMCO—extra corporeal membrane oxygenation.

As medical director of the NICU, Duara also oversees clinical trials, testing the most promising new therapies, like the major National Institutes of Health study on whole-body cooling to reduce neurological damage. Now it’s the standard of care in babies who had breathing interrupted just after birth, although not every hospital offers it. Duara and her research staff have collaborated on dozens of NIH and industry studies, including two under way and two more about to start.

Researchers at the Neonatal Developmental Biology Laboratory are also searching for ways to help at the molecular level—even before birth. Cleide Y. Suguihara, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of pediatrics, directs the lab. She and her colleagues are looking at genetic pathways and working with stem cells to treat injured lungs and reduce pulmonary hypertension. “All the research in this lab always has some clinical significance,” Suguihara says.

Always Learning, Always Teaching

At the core of academic medicine is advancing knowledge.

“We mainly teach our trainees three things,” says Ilene R.S. Sosenko, M.D., professor of pediatrics, and obstetrics and gynecology. “The first is how to take care of babies. The second is how to teach others. And the third thing is how to do research.” Sosenko also is the associate director for clinical development and outreach for the Division of Neonatology.

Outreach. That’s a word they take seriously in the division. Just since 2003, neonatalogy faculty have published 83 journal articles and dozens of book chapters. A new textbook, The Newborn Lung, was edited by Bancalari. UM faculty also tour the world, visiting other units and giving lectures—and there’s a waiting list of physicians wanting to train at the Miller School.

“In addition to having trained more than 100 clinical fellows, we also train the pediatric residents,” says Sosenko. “And many neonatologists or pediatricians from around the world elect to come do an observership here, and they take that knowledge of how we do things back to their country.”

Suguihara’s developmental biology lab also trains future physicians and scientists, including clinical and research fellows—and even ten undergraduates since the mid-1990s. One undergrad had a special relationship with the faculty and staff.

“It was a great opportunity to work in the lab, and it taught me a lot about research,” recalls Heather Yeckes-Rodin, M.D., a Miller School alum who is now a hematologist-oncologist in Stuart, Florida. She was home from Duke University in the summer of 1996 and worked in the lab—but it wasn’t her first visit to neonatology at UM. She spent time there in 1975—as a preemie. She credits her time in Suguihara’s lab with helping her decide to pursue medicine.

“Oftentimes, there’s no rhyme or reason to why people have premature babies,” says Yeckes-Rodin, now the mother of a 2-year-old girl. “All of the work they do there, what Cleide does, is wonderful, just monumental research.”

Success Stories

Nearly 90 percent of preemies now survive, so the focus has widened from the first hours and weeks to years and decades of life. “In gestation and birth, things are happening very fast and they should happen in a certain way,” says Bancalari. “If that way is disrupted, then you may face consequences for the rest of your life.” Charles Bauer, M.D., associate director of neonatology, and Emmalee Bandstra, M.D., professor of pediatrics, and obstetrics and gynecology, both have NIH-funded research on long-term survivorship of premature birth. They try to follow every baby that comes through the unit.

Alex Germani lost his short fight for life, but his twin brother survived. After 12 weeks in the NICU, Diego went home, still small—less than 6 pounds—but healthy. That was five years ago. Now he has two little brothers, ages 3 and 1.

Lauryn Overton, the preemie who went home around Christmas, is a high school senior now, but her mom, Herty, still remembers. “They said there was a one-in-a-million chance that the baby could be viable. My husband said we wanted to be that one,” Overton says.

“We got our miracle.”

Giving Birth to a Dream

Project New Born

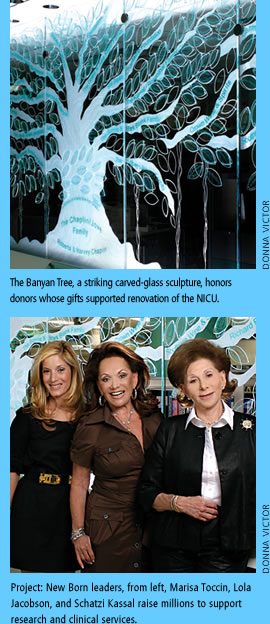

Marisa Toccin weighed barely 2 pounds when she came into the world in 1977. During her weeks in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Holtz Children’s Hospital in Jackson Memorial, her family kept a vigil at her side, consumed with worry, prayer—and helplessness. Marisa Toccin weighed barely 2 pounds when she came into the world in 1977. During her weeks in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Holtz Children’s Hospital in Jackson Memorial, her family kept a vigil at her side, consumed with worry, prayer—and helplessness.

But Marisa’s grandmother, Lola Jacobson, isn’t the kind of person to stand idly by. When she learned about a handful of women who had already been through this—the “seven babes” of Project: New Born—she signed on.

“There were seven women who started the charity,” recalls Schatzi Kassal, the founder and executive director of Project: New Born. It started when the director of pediatric surgery, Mark Rowe, M.D., treated her son, Bubba. Grateful, Kassal wanted to do something to help. When Rowe suggested that she fund some research, she founded Project: New Born.

That was 35 years and $10 million ago.

Jacobson joined the group in its fifth year and got to work. To encourage the ladies to donate, she approached Tiffany & Co. and asked for a donation of diamond bumblebee pins. When Tiffany’s then-general manager Lisa Perri-Molina asked how many pins she would need, Jacobson replied: “Probably only ten.” The ladies loved the jewelry, and ten pins turned into more than 100 members.

The “Tiffany Society” was quickly raising $100,000 a year for Project: New Born. It came on the heels of “Diamond Babes” and was followed by a host of other events, including ambassador parties and international wine events. The flagship is a yearly luncheon and fashion show hosted every November by Stanley Whitman, Bal Harbour Shops, and Southern Wine & Spirits.

Two years ago, Eduardo Bancalari, M.D., director of the Division of Neonatology, needed $1 million to refurbish the NICU. Kassal and Jacobson answered the call. Neiman Marcus Bal Harbour came on board early, providing the gold and diamond banyan leaf pins that helped the Banyan Society of Project: New Born take root. Support came, too, from many others, including Bubba, the former NICU patient who’s now the vice president of Crown Wine and Spirits.

Visitors to the unit can now see the fruits of the group’s labor in both the beautifully renovated facility and the Banyan Tree—a stunning carved-glass sculpture honoring the donors who answered the call. Interior designer Diane Sepler spearheaded the tribute and brought glass artisan Peter Solice on board.

The refurbished NICU opened with a ribbon-cutting in November 2007, and 30-year-old Marisa Toccin, now a third-generation volunteer with Project: New Born, was there. “I walked into the unit and saw a father really struggling and really concerned,” she says. “I explained that I had been born there. And suddenly he had tears in his eyes and he said, ‘I’m so happy to see you here today. You’re giving me hope that everything will work out okay.’” |

|

|

|