|

|

On the morning of March 17 a young Haitian man bathes, dresses in his best clothes, and prepares to make the bus trip to Bernard Mevs Hospital in Port-au-Prince. He does not look in the mirror. He will later explain to his doctors that he never does.

Since childhood, his severe cleft lip has brought him despair so profound he has contemplated suicide. Today he will travel to Haiti’s capital for the free surgery he heard advertised on the radio. Tomorrow he will be photographed—mirror in hand, his lip repaired, smiling.

That same weekend, a team of students, residents, fellows, nurses, and physicians led by Vincent DeGennaro Sr., M.S., M.D., assistant chief of surgery at the Miami VA Medical Center, along with Seth Thaller, M.D., D.M.D., professor and chief of the Miller School’s Division of Plastic Surgery, repaired 16 cleft lips and palates, performed a hernia surgery, and treated a burn victim, a child who bit an electrical wire. That same weekend, a team of students, residents, fellows, nurses, and physicians led by Vincent DeGennaro Sr., M.S., M.D., assistant chief of surgery at the Miami VA Medical Center, along with Seth Thaller, M.D., D.M.D., professor and chief of the Miller School’s Division of Plastic Surgery, repaired 16 cleft lips and palates, performed a hernia surgery, and treated a burn victim, a child who bit an electrical wire.

“I believe that everyone enters the field of medicine for some altruistic reasons,” says Thaller. “This experience allows practicing surgeons, physicians, residents, and medical students to step back from their daily routine and examine themselves as a person. It gives us an opportunity to develop our medical skills beyond the usual confines of traditional medical education and training. We learn the importance of the value of giving back. This may be taught in school, but there is nothing compared to living the experience and being touched directly by another person.”

Project Medishare

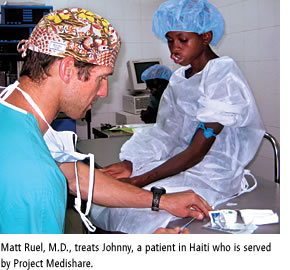

The plastic surgery team traveled to Haiti in March as part of Project Medishare, a nonprofit that has been working for more than 12 years to improve the well-being of Haitians by establishing sustainable health care programs.

In June the group visited Port-au-Prince for another series of surgeries and to train local surgical residents, whose desire to learn and to serve is often challenged by a staggering lack of resources.

Working in the spare operating rooms at Haiti’s Hôpital Universitaire La Paix was a crash course in mission medicine for fourth-year medical student Gia Hoosien. In addition to lacking basic comforts like reliable bathrooms, air conditioning, fans, sheets, and towels, there were also very few monitors, sinks, IV poles, or gurneys, and the doctors operated under the illumination of one light bulb, when they normally would use four.

Even running water was scarce. “The hospital has a tank that fills each night,” says Hoosien. “When it’s gone, it’s gone. We tried not to drink too much, and we brought surgical soap that doesn’t require water. Not having some of the basic amenities really makes you think twice about each and every resource you have and how to make the best use of it.”

Although they were there to provide cleft lip and palate care, the group did not turn away others in need. A teenage girl appeared at the clinic, unable to blink or close her right eye to sleep. As a child, a tumor had been removed from beneath her right eye, she told the doctors. It left a large comma-shaped scar that contracted over time, pulling down the skin around the lower lid. With her eye exposed 24 hours a day, she was at great risk for blindness.

Hoosien shadowed plastic surgeon Joe Garri, M.D., D.M.D., as he performed a full eyelid reconstruction on the girl, removing extra skin from her upper lid and moving it to beneath the eye. During the operation, community anesthesiologist James Lesniak, M.D., adeptly worked with limited resources to manage her anesthesia. Using a stethoscope taped to the girl’s chest and anchored in his ear like a hearing aid, Lesniak monitored her breathing for the length of the surgery, while Hoosien took blood pressure by hand (“the old-fashioned way”) at five-minute intervals, allowing the team to assess if the girl needed more IV fluids or IV medicine.

“Clinical skills were applied in the purest sense,” says Hoosien. “It made me realize that you need everything you learn in medical school—nothing is extraneous.” “Clinical skills were applied in the purest sense,” says Hoosien. “It made me realize that you need everything you learn in medical school—nothing is extraneous.”

The operations, which Hoosien says are “on par with the surgical care you would receive in the U.S.,” have changed the lives of children like 5-year-old Judlie, who was born with a cleft lip and palate. When Judlie was 18 months old, Project Medishare doctors, in collaboration with a charity called The Smile Train, performed surgery to repair her cleft lip, then followed up with a cosmetic revision of the lip on a subsequent visit. On this trip, the team repaired her cleft palate.

“We’re there to learn how to be the kind of attendings we want to be someday,” Hoosien says. “It inspired me to come home and learn.”

In addition to Haiti, groups of students and their physician mentors currently make regular trips to destinations including the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Peru, and Ecuador. “My generation of doctors is adventuresome,” says Hoosien. “Students are drawn to the Miller School from around the country for exactly these opportunities. We’re ready to get out there.”

Miller School Dean Pascal J. Goldschmidt, M.D., wants to harness this enthusiasm for global outreach and provide opportunities for it to grow. “It is my vision to make this type of service to resource-poor areas a mandatory part of our curriculum,” he says.

Medical Students in Action

“You know your children have grown up when you start following their example,” says Project Medishare veteran DeGennaro Sr.

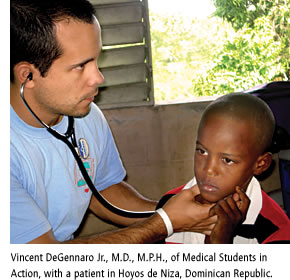

He is talking about his son, recent graduate Vincent DeGennaro Jr., M.D., M.P.H., whose interest in medical missions inspired his father’s work in Haiti.

The younger DeGennaro leads a student group called Medical Students in Action. In the last few years, a cluster of four remote towns an hour west of the Dominican Republic capital of Santo Domingo has been transformed as a result of their work.

Medical Students in Action, which was founded in 2003 by former Miller School student Mikel Llanes, M.D., along with DeGennaro and a few physician advisors, made inroads in the Dominican Republic by working with a community nonprofit, local schools, and the area’s sole clinic to provide quality care, education, and infrastructural support to the surrounding communities.

During weeklong visits in January and March, the organization operates a rotating clinic, using local sites to host educational sessions on topics like nutrition, women’s health, and safe sex, and to administer EKGs, echocardiograms, dental checkups, and Pap smears.

For the medical students, the experience provides a unique opportunity to step out of the classroom and practice their clinical skills in a real-world setting. For patients, these screenings often lead to lifesaving follow-up care.

In the past year, Medical Students in Action has diagnosed and funded procedures for a 28-year-old mother of four with pre-invasive cervical cancer, a 7-year-old with an atrio-septal defect in her heart, and a 23-year-old who was in danger of losing his leg due to an infected femur bone. In the past year, Medical Students in Action has diagnosed and funded procedures for a 28-year-old mother of four with pre-invasive cervical cancer, a 7-year-old with an atrio-septal defect in her heart, and a 23-year-old who was in danger of losing his leg due to an infected femur bone.

“I took him to the hospital and said, ‘This guy needs to have surgery,’” says DeGennaro. “The doctor said, ‘No he doesn’t—he needs antibiotics.’ We buy the antibiotics, he doesn’t get better, we take him back, they say, ‘He doesn’t need surgery.’ Basically they don’t have the resources. So we found a private doctor to operate on him. It cost $750. Here it would’ve cost around $10,000.”

Jeanette Mladenovic, M.D., M.B.A., senior associate dean for graduate medical education, brought her daughters on a trip with Medical Students in Action in January. “These kinds of experiences for students allow them to see a different need for medical care than they see in the United States,” she says. “It often reminds them of why they wanted to go to medical school in the first place. Sometimes, it also helps direct their future career, as there are now much greater opportunities in health policy, public health, and global medicine.”

Medical Students in Action has dug wells, built latrines and cisterns, and constructed a fence around a local school. They are working with the local government to provide access to clean water for each town, and they continue to build the local clinic’s capacities by providing medical equipment, a laptop computer with a growing 1,500-patient database, and medications year-round.

As a result of the fundraising efforts of physician advisors Steve Chavoustie, M.D., and Donato Arguelles, M.D., in September 2007 Medical Students in Action hired its first full-time employee based in the Dominican Republic. DeGennaro hopes the growth will eventually lead to collaboration between the Miller School and a hospital in Santo Domingo for the development of a one-month rotation for fourth-year medical students.

“You can’t hide from bird flu and SARS and HIV by putting up fences between countries,” DeGennaro says. “Modern physicians have to be trained to treat patients in all kinds of environments.”

Emmaus Medical Mission

Orlando E. Silva, M.D., J.D., can’t talk about his mission trips to Guatemala without coming to tears. First, there are the patients. Like the 8-year-old girl who walked to the clinic hand-in-hand with her 5-year-old brother, carrying her 5-month-old sister on her back, while her parents worked. Then there are the premed students and teenage volunteers. After being separated from their iPods and computers, they reconnect with their parents, who are physicians on the trip, to share a meal, work side by side, and even fall asleep on a shoulder.

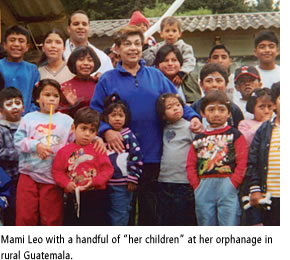

Then there is “Mami Leo”—Leonor Portela, a 72-year-old Cuban-American who moved to Sunpango, in rural Guatemala, 23 years ago to start an orphanage. There are “her children,” hundreds of them who have come to her home to be loved and nurtured, including a boy who had been dipped in scalding water by his parents.

Mami Leo carried him, mute and lifeless, in a harness for days. On the fourth day, as she put him to bed, he broke his silence to ask her, “¿Porque me quieres?”—“Why do you love me?” He now attends law school, works with Mami Leo, and volunteers during the mission trips.

This is why Silva, associate professor of clinical medicine at the Miller School and director of breast cancer education at Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, pauses at length between his stories, waiting for the tears to pass.

“One of the greatest feelings is when you get off the bus, those gates swing open, and you see those little children running toward you with Mami Leo in the middle,” says Silva. “It’s touching heaven on earth. When you go on these missions, oftentimes there’s something that you feel—and what you’re feeling is the presence of God. You don’t recognize it until you look into those children’s eyes, and then you see it, looking right back.”

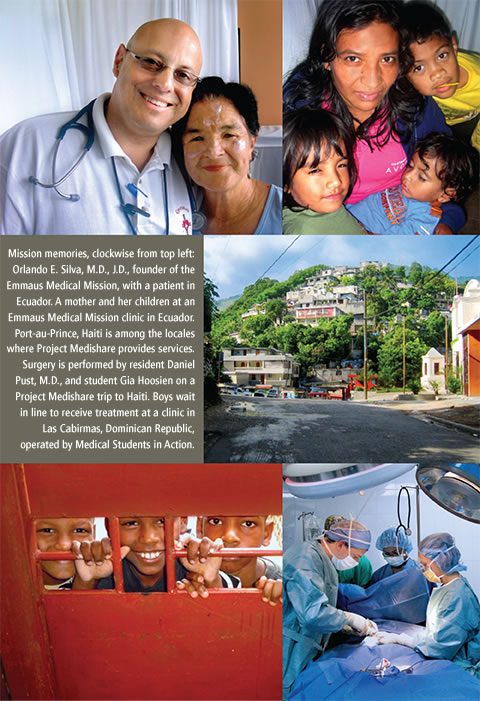

In 2002, after meeting Mami Leo at a fundraising event for her orphanage, Silva began to organize trips to Sunpango, 45 minutes outside Guatemala City. To date, more than 1,500 people from around the world have participated in Silva’s missions, named Emmaus for one of Silva’s favorite Bible passages. Mission alums include Miller School physicians Alejandro Forteza, M.D., associate professor of clinical neurology; Luis Raez, M.D., associate professor of clinical medicine; Elio Donna, M.D., associate professor of medicine; and UM premed and Miller School students.

Since the program’s inception, trips to Peru and Ecuador have been introduced, as well as the occasional “commando” trip, where a small team travels down for just over 24 hours to deliver gifts on Christmas or perform a handful of cleft lip and palate surgeries.

Silva has rules for his trips. Physicians and students must hug the patient, shake his or her hand, introduce themselves, and make eye contact. Every physician needs to teach one medical “pearl” per case, each student must ask one question per case, and students must keep a notebook where they record at least one line per case that they can reflect on later.

“The kids here have the same complaints as children in the U.S., they just don’t have access to care,” says fourth-year medical student Heather Allewelt, who traveled to Ecuador with Emmaus in March and plans to go to Guatemala. “You go into medicine to help people, and you can lose sight of that.”

Allewelt was particularly moved by the women she treated in a clinic the military arranged in the mountains of Cuenco for Emmaus. She recalls, “The military set up a clinic for us in this big arena—it must’ve been a sports arena. And they bused people in. We saw more adults here than we saw at the orphanage. I was most touched by the women. We would prescribe medications for them or their children and they would always ask, ‘How much does it cost?’ They were afraid. And we got to say, ‘Nothing.’”

“It makes a difference for everyone involved,” says Silva. “For those who have been forgotten, it makes a huge difference to get medicine they need. It makes a difference to us because it humanizes us and makes us reconnect with the truly important things in life, like love and forgiveness and family.”

The 100-person team treats up to 6,000 patients over two and a half days. Patients, some of whom have been waiting in line for more than ten hours, check into the clinic, get triaged, and are directed to the available specialties. Silva calls it “pure medicine”—a patient in need, a doctor who can help, and medicines to heal, without the bureaucracy of insurance forms and the worry of legal ramifications.

“It should be a required part of our curriculum,” says Allewelt. “Not only for the sheer number of patients you see, but the variety of conditions. On every level it was life-changing.” |

|

|