|

|

A large hall at the Church of the Open Door on Miami’s Northwest Eighth Avenue is buzzing as dozens of high school and college students, some dressed-up in finery, mingle with each other, family, and friends. The students, minorities who are mostly Hispanic or black, chat excitedly about—of all things—studying medicine, though most are years away from entering the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine or any other medical school.

In one corner, a large cake with “Congratulations” artfully splashed across it seems to be “just desserts” for the students who spent seven weeks of their summer rigorously studying everything from anatomy and physiology to SAT and MCAT prep. The students are all part of the Miller School’s long-esteemed Miami Comprehensive Model for Health Professions Education program, which has helped prepare many minority students for studies in the health care field and especially for medical school.

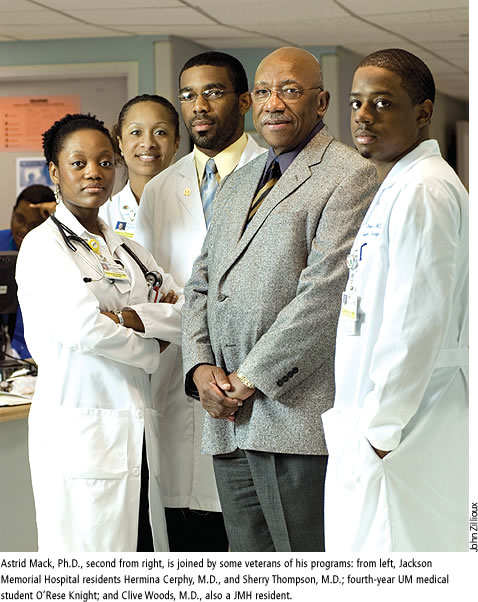

At the church hall, it is also hard to miss Astrid Mack, Ph.D., the man seemingly capable of being everywhere and doing everything all at once. Even on this festive day that marks the end of another summer program, Mack, the Miller School research associate professor of medicine, associate dean for minority affairs, and program director, is dishing out some last-minute advice to a group of students. A few minutes later, the sickle cell disease expert makes no bones about hunting down extra tablecloths and spreading them himself to ensure the special occasion comes off with the same dignity he demands of his young charges.

For 20 of the 31 years that the Miami Comprehensive Model program has been housed at the Miller School, Mack has been insisting on high academic achievement—but he does so while lending a listening ear to students’ real-life situations and giving fatherly advice.

“Maybe grandfatherly,” he laughs, then adds, “I’m so much more like a warden, but they know I’m doing it for their benefit.”

Mack is serious in demeanor, but the more than 100 students who enroll in the program for several weeks each summer know that he, along with the University, are primary backers of their sometimes delicate dreams to become physicians. And though his own son, Kyle, graduated from the Miller School in 1999 and is a pediatrician at a Chicago hospital, the students become like his own children, and the program’s mission and his personal goal become one.

“He was already admired and respected by everybody, and he understood the minority community as a whole,” says Bernard J. Fogel, M.D., Miller School dean emeritus who asked Mack to join the program in 1985. “He took over the program and became the guardian of trying to increase minority enrollment. The success rate was astronomical.”

The program started in 1976 as a means of increasing the number of African-American students at UM’s medical school. Since then, the program has gone through several permutations, but the success rate has remained high—more than 60 percent of students passing through the program have earned M.D.s at Miller or other medical schools, and about 90 percent overall have entered other health professions and biomedical sciences.

From ‘Boot Camp’ to Doctor at Jackson

From the time he was 10, Samora Cotterell knew he wanted to be a physician. The microbiology major was pretty sure he had the intellect and stamina to make it through medical school. From the time he was 10, Samora Cotterell knew he wanted to be a physician. The microbiology major was pretty sure he had the intellect and stamina to make it through medical school.

Unfortunately, Cotterell had no clue how to convert his aspiration into reality. So while a student at Florida Atlantic University, in the spring of 1999 he met with the school’s pre-professional committee and inquired how to get into UM’s Miller School of Medicine.

“To improve my strength as an applicant, they recommended that I enroll in Dr. Mack’s program,” Cotterell recalls. “I was told that among other things, the program would help me with the MCAT (Medical College Admission Test).

“The first impression you get from him is that he’s a very patriarchal type person, and you get a sense that you’re his child and all the people involved are like his family,” says Cotterell, who enrolled in the program that summer. “The second impression you get from him is that he means business!”

Over the course of seven weeks, Cotterell experienced a total immersion into immunology, gross anatomy, and other medical school topics, two full-length MCAT practice tests, and was exposed to many medical professionals. “It was like a boot camp for medicine,” Cotterell says.

Cotterell was later accepted into the Miller School and earned his M.D. degree in 2004. He now works as a hospitalist at Jackson Memorial Hospital. |

Before college, Sherry Thompson, M.D., was leaning toward a career in medicine, but she also toyed with becoming a musician. While an undergraduate at UM, she enrolled in the summer program and was smitten by medicine through the early exposure. She went on to earn her M.D. from the Miller School in 2005 and is now a third-year pathology resident at Jackson Memorial Hospital. “We did well partially because everyone in the program seemed so vested in our academic career. You didn’t want to let them down, especially Dr. Mack,” says Thompson. “He worked so hard you really didn’t want his efforts to go to waste.”

Clive Woods, M.D., now an orthopaedic resident at Jackson Memorial, was set on a medical career but credits Mack and the UM program for helping him lay the adequate groundwork. “What I learned was how to study strategically and make better use of my time,” says Woods, who enrolled in the seminar the summer between his junior and senior years at Florida State University before heading to Meharry Medical College. “There are residents at Jackson and in many other residency programs who were helped by the program and Dr. Mack’s dedication.”

For seven weeks last summer, 112 students from Miami area high schools and several Florida colleges followed the footsteps of Thompson, Woods, and dozens of other medical practitioners who passed through the program’s doors.

On the first day, Miller School Dean Pascal J. Goldschmidt, M.D., assured the new recruits they all had the potential to become “great medical students and, one day, great doctors.” And, he stressed, they were needed at UM, at other medical schools, and later in the wards of the nation’s hospitals. “When you want to build a great basketball team, you don’t just look for players in a certain population,” said Goldschmidt. “You want to look at everybody. If you overlook some people, you could be missing out on recruiting great talent.”

That talent pool could include 15-year-old Monique Miller, who participated in last year’s program. She wants to find a cure for sickle cell disease. “The program shows us all the things we can do right now to help us get into the medical field,” Miller says.

And that has been one of the strengths of the Miami Comprehensive Model.

“One of the reasons we have these high school programs is that experience has taught us we must go back, and the further we go back into the education pipeline to begin to prepare these youngsters for professions like medicine, the better off we’re going to be,” Mack says. “The important thing is to increase the applicant pool because we have too few minorities in that pool.”

In 1991 the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) launched a campaign that sought to enroll 3,000 underrepresented minority students in medical school by 2000. More recently, AAMC launched AspiringDocs.org, a Web-based program designed to increase the numbers of minorities applying to medical school.

But “no matter what we do—and we are trying to do many things—we’re looking at statistics that tell me we really have to convince policymakers and the public that we need all of our young people to do well in school and not just those from areas with high tax bases,” says the AAMC’s Charles Terrell, Ed.D., vice president of diversity policy and programs. “Otherwise, we are likely to face significant shortfalls in Latino and African-American students going to medical school.”

Programs to increase minority enrollment are still necessary, says Mack, adding that he has come across too many minority students who are discouraged early on from studying medicine simply because they don’t have a 4.0 G.P.A.

Program Helps toward Med School Success

Listen to Shaunté Butler talk about becoming an obstetrician/gynecologist or a cardiothoracic surgeon, and you get the impression it’s part of her destiny. At 16,  the high-achieving Miami Northwestern Senior High School medical magnet program student is looking forward to starting college and committing herself to more than eight years of study. the high-achieving Miami Northwestern Senior High School medical magnet program student is looking forward to starting college and committing herself to more than eight years of study.

But to help guarantee success, Shaunté last summer enrolled in the University of Miami’s Summer Science Enrichment Program. “I discovered I liked science in middle school, and I decided I wanted to become a doctor,” says Shaunté. “What I am learning here is going to help me achieve my goal of getting a scholarship to a top college and a top medical school.”

“Growing up with my grandmother, education was a requirement but I didn’t have the career guidance my daughter is getting now,” says Shaunté’s mother, Lisa Winchester, who was raised in Tobago. “Shaunté is such a dedicated student, and people like Dr. Mack help her shine brighter.”

At the end of the program, Shaunté and other class members had to individually make final presentations on a public heath issue in a foreign country. Shaunté executed an elaborate presentation on substance abuse in Russia.

“She had so much information—from the CDC, from the library. The whole thing was done so well,” says a proud Winchester. “The students were really impressive. It’s amazing what they all accomplished so quickly.” |

On the other hand, Mack says, over the years he’s built solid relationships with teachers at institutions such as Miami Northwestern Senior High School—from which many of the program’s students come—which sends many students to college and the health care field through strong curricula and support. “He is a dedicated educator who works tirelessly to bring minority students to their highest level,” says Adrienne Weinstein-Lowy, Miami Northwestern’s medical magnet lead teacher.

The Miami Comprehensive Model program continues to serve as a valuable feeder to the Miller School and other medical schools around the country. Today, the Miller School has a student population that is 26 percent minority, with a majority of that being Hispanic students. “UM has been helping to fill this need for a long time and has been doing a good job,” says Mark O’Connell, M.D., senior associate dean for medical education at the Miller School. “We have seen that you can attract youngsters to careers in health care if you expose them to the right role models and the right mentors.”

Mack has been unwavering in this commitment.

“The students who join the program really have the passion,” says Mack. “UM provides a highly structured, supportive environment. I provide encouragement.”

|

|

|