|

One hundred percent fatal. That’s how trauma physicians

describe a bilateral above the knee traumatic amputation.

No one can survive the profuse bleeding unless competent

help arrives immediately. One hundred percent fatal. That’s how trauma physicians

describe a bilateral above the knee traumatic amputation.

No one can survive the profuse bleeding unless competent

help arrives immediately.

Without a miracle, race car driver Alex

Zanardi would be dead in four minutes. Help arrived in

just 19 seconds.

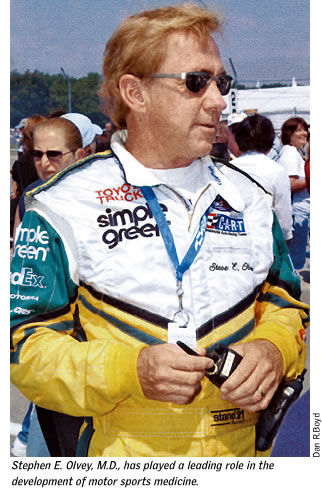

“The Zanardi crash was a situation where an individual sustained

an injury that was considered universally fatal,” says

Stephen E. Olvey, M.D., associate professor of neurological

surgery and one of the physicians who treated Zanardi

that day.

Zanardi was saved, not only by the physicians

who treated him at a German race course in September

2001, but

by a long investment in safety.

Olvey has now written a book about his

40 years of providing emergency medicine to injured race

car drivers. Rapid

Response: My inside story as a motor racing life-saver tells

the story of the evolution of motor sports medicine,

an

effort led by Olvey and a handful of other physicians.

Olvey first worked as a track physician

in Indianapolis in 1966, when a hearse served as an ambulance

and intensive-care

specialists were nowhere to be found. “In Milwaukee

the medical director was an Ob/Gyn,” he recalls.

And in the 1960s, one out of seven drivers

involved in a crash was killed.

“I started the first program where the same physicians went

around to the races,” says Olvey, who is also

director of the Neurosurgical Intensive Care Unit at

Jackson Memorial

Hospital, but who grew up in Indianapolis. “We

standardized things.”

Olvey recounts the inadequacy of motor

sports medicine through the 1950s and ’60s, when

deaths from fire and head injury permeated the sport.

Swede Savage crashed

in an inferno in 1973 and died a month later from complications

related to contaminated plasma. Gordon Johncock suffered

a badly broken leg racing in Milwaukee—then was

accidentally dumped from the back of the ambulance.

In 1975, as the new assistant medical

director at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, Olvey was

put in charge

of organizing more

consistent and better medical care at the various Indy

car tracks. By the early 1980s, a trained physician—often

Olvey—would usually be on the scene within 30

seconds after a crash. Tracks offered medical facilities

equipped

like trauma hospitals and required medical helicopters.

In 1996 driver Emerson Fittipaldi, who

lives part time in Miami, crashed at Michigan International

Speedway,

severely fracturing his cervical spine. Not agreeing

with the care

offered in Michigan, Olvey flew Fittipaldi to UM/Jackson,

where he had successful surgery led by Barth A. Green,

M.D., F.A.C.S., professor and chairman of the Department

of Neurological Surgery, and Frank J. Eismont, M.D.,

professor and chairman of the Department of Orthopaedics.

Olvey says many physicians were focused

on saving an injured driver’s life but not thinking about getting them

back into a race car. Instead, he and his colleagues worked

on restoring drivers’ ability to compete.

Zanardi, the driver who lost his legs,

returned to the German track where he was injured two

years later

to

drive his last 13 laps with prosthetic legs.

At full speed. |